China is testing the UK and Europe’s balance between trade and human rights

In Europe, concerns are growing about human rights violations in Chinese supply chains. In response, parliaments are forcing their governments to reevaluate their trade and business relationships with Beijing.

In Europe, concerns are growing about human rights violations in Chinese supply chains. In response, parliaments are forcing their governments to reevaluate their trade and business relationships with Beijing.

Two recent votes show how, in 2021, lawmakers and bureaucrats will face off on China.

A “genocide amendment” in the UK’s parliament

In 2020, as it left the European Union, the UK radically altered its relationship with China, banning Huawei from its network, opening a path to citizenship for Hong Kongers, and restricting foreign investment in select industries. Much of that change was forced upon the government of UK prime minister Boris Johnson—a Sinophile with little appetite for angering Beijing—by an increasingly hawkish parliament and an active group of human rights campaigners.

The tensions between parliamentarians and their government on China have come to a head during debates in the House of Commons, including on bills governing broadband access and foreign investment screening. In the most recent episode, the government narrowly won a vote on an amendment to a bill outlining how the UK should implement trade deals.

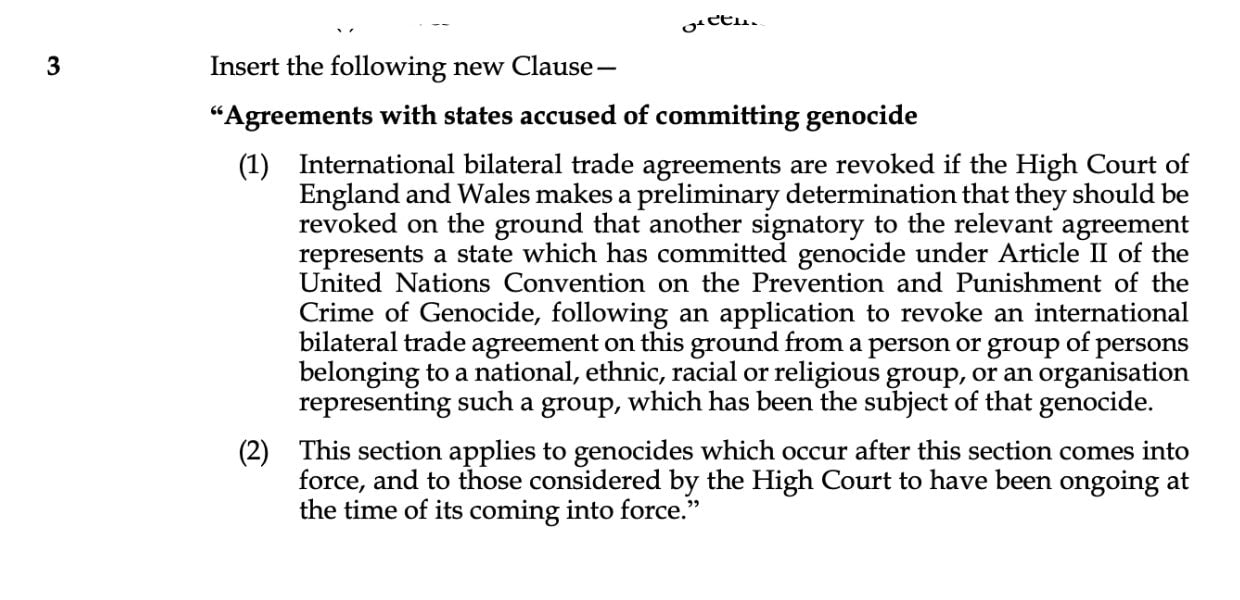

The amendment would have empowered the UK High Court to make a preliminary determination that a genocide is happening in any given country, and to then force the government to revoke bilateral trade agreements with that country. The amendment’s authors made clear that they were targeting China—but it also could apply to other countries.

The amendment lost by a margin of 11 votes. But it marked a significant rebellion against the government, which argued that authority over trade deals should reside with elected officials, not judges, and that giving the court such authority would weaken “the separation of powers in Britain’s constitutional system.” The rebels have already revised their amendment (pdf) and peers will vote on it in a week, followed by the Commons.

Clearly, this debate isn’t over. That it happened at all is a testament to how radically UK lawmakers’ perception of China has changed for the worse since the start of the pandemic, and to how prominent the debate around human rights in China has become in British politics. Last week, UK foreign secretary Dominic Raab made concessions aimed at placating the members of his own party who are considered China hawks. The concessions include a strengthening of existing rules forcing British businesses to cut off suppliers who violate human rights in their supply chains, and a promise to conduct an “urgent review” of policies on goods (like security cameras, for example) exported to the Xinjiang region of China.

Johnson’s government insists it has no plans to sign a free trade deal with China. But it’s an idea the UK has long flirted with. And part of the impetus for Brexit was so that London could be free to sign advantageous bilateral deals with countries in the Indo-Pacific.

There’s a lot at stake. In 2019, the total value of UK exports to China was more than £30 million, and China was the UK’s sixth largest export market.

Can the rest of Europe continue to compartmentalize?

The rest of Europe is similarly grappling with the question of whether it should hitch its economic future to a country that doesn’t share its values. On the one hand, China is the center of gravity of the world economy; opportunity and growth come from there, including possible solutions to shared challenges like climate change. On the other, the differences of values being discussed are significant; they include whether forced labor and the trampling of civil rights can ever be tolerated in the name of stability and security.

That tension became all the more untenable last week, when the US accused China of committing genocide against Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang. (It’s a charge the Chinese Communist Party vigorously denies.)

EU leaders made their choice a few weeks ago when they announced the terms of a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) with China: They believe investment can bring China more in line with their values. (It’s the same belief that motivated the US’ outreach to China in the 1970s and later early 2000s, when China joined the World Trade Organization. And yet that school of thought hasn’t born fruit, as China has grown into a capitalist juggernaut, but not a democracy.)

But read between the lines of the EU’s announcement and the message is clear: Even if that change doesn’t happen, Brussels doesn’t plan on turning its back on its second-biggest trading partner. In a blog post, Europe’s chief diplomat, Josep Borrell, wrote that “unlike in Washington, in the European Union there is not apparent tendency towards a strategic rivalry that could lead to a kind of new ‘Cold War,’ nor towards a broad economic decoupling.”

It may have to, though, if its parliament has anything to say about it. Just last week, members passed a resolution on Hong Kong in which they inserted language about the CAI, implying they could oppose its ratification:

China’s reaction was swift and predictable: It accused the European Parliament of interference and defended its actions in Hong Kong.

Some critics of the CAI say that, in substance, it gives European companies in China few new benefits, while others expect it will create a raft of new opportunities for them. But no one disagrees that, symbolically, it’s a win for China. In the eyes of the world, it weakens the US’ genocide designation (which happened after the CAI was agreed to). After all, if a genocide were happening somewhere, surely the EU wouldn’t enter into a business arrangement with that country? And it seems to put the EU in Beijing’s corner just as US president Joe Biden enters office, seeking to create a joint strategy on China with fellow democratic nations.

But the CAI needs parliamentary ratification to become law—and in the next few months, as the text is translated and submitted for a vote, there’s a chance it won’t get it. In a previous interview with Quartz, Reinhard Bütikofer, a German member of European parliament who chairs the delegation for relations with China, said the debate “will boil down to just one question,” which is, can the EU deepen trade relations one day, while challenging China’s human rights violations the next?

Bütikofer knows which answer he favors: “Compartmentalization is not the right approach and we should leave it behind.”