When Boris Johnson and his Vote Leave allies launched their vision for a post-Brexit “Global Britain,” the UK pinned its hopes for geopolitical relevance in large part on deepening ties with Asia, and especially China. Four years later, Britain has become a hub for the West’s growing skepticism of China, and Covid-19 was the match that lit the fuse.

The hostility generated by allegations of China’s cover-up of the virus’s early spread, and Beijing’s strident defense of itself, have spilled over into all parts of the China-UK relationship. It is a case study in what has gone wrong for China since the start of the year—and perhaps for Britain’s post-Brexit foreign policy too.

Since the start of the pandemic, London and Beijing have butted heads over Hong Kong, Huawei, and more. The British government has put forward a proposal to screen and block certain mergers and acquisitions from Chinese investors on national security grounds. And new lobby groups founded this year are leading an internal campaign to reshape Britain’s ties to China, including the China Research Group, a think tank led by MPs Tom Tugendhat and Neil O’Brien that aims to promote “fresh thinking” about China in the UK, or the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China (IPAC), an international group of parliamentarians who seek to counter what they see as the threat posed to liberal democracies by China’s rise.

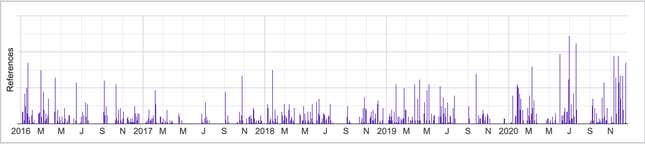

When the Conservative Party won the 2019 general election in a landslide, most members of Britain’s Parliament would either have thought of China in positive terms reminiscent of the “golden era” that London not so long ago spoke of ushering in with Beijing—or not thought of it. Even political insiders marvel at how quickly the pandemic turned China from an issue many people in government “weren’t particularly interested in,” as Alicia Kearns, a Conservative Party MP, put it, into a toxic one.

“Come 2020,” says Kearns, who sits on a committee with oversight over foreign affairs, and “everyone’s talking about China because of the virus.”

Hanging up on Huawei

Perhaps no company more exemplifies the downward spiral in the two countries’ relations this year than Chinese telecom giant Huawei.

Long barred from the US over national security concerns, the telecom equipment maker’s footprint in Britain offered it a springboard to grow into a global giant. Almost all UK telecom providers use its products—it has supplied close to 40% of the radio equipment that helps UK devices connect to fourth-generation (4G) mobile networks. But in July, it was banned from the buildout of the UK’s 5G network.

It’s an about-face for a government that was initially reluctant to ban Huawei, even as the US lobbied allies hard to shun the company. In January, the UK had said Huawei could supply up to a third of the non-core parts of its 5G network. But it was forced to backtrack after a pressure campaign from UK parliamentarians and influential right-wing think tanks like the Henry Jackson Society, who see Huawei as a tool of the Chinese Communist Party that could compromise Britain’s critical infrastructure. To a certain extent, intelligence officials seem to agree.

In March, 38 MPs from the government’s own party broke ranks and tried to force a Huawei ban by amendment. In the end, though, it was American sanctions on Huawei that pushed the UK to ban the company and call for stripping its gear from the networks by 2027, because British intelligence said it could “no longer offer sufficient assurance” that the national security risks of the firm’s equipment could be “mitigated.” Countries like Belgium and Sweden have since made similar decisions.

The Huawei vote solidified the formation of a group of MPs, led by lawmaker and former Tory party leader Iain Duncan Smith, who are generally hawkish on China, and are known as the “China rebels.” Luke de Pulford, a coordinator of IPAC who’s been especially active around the crackdown in Hong Kong, says the vote taught the rebels that “ultimately, governments respond to force majeure,” setting up many confrontations to come.

In many ways, the Huawei question “clarified…the challenge we’re facing in China,” argues Tugendhat of the China Research Group, “not just in economic terms, but in terms of what it means for the global order.”

Hong Kong and the Uyghurs

This month, Hong Kong lawmaker Ted Hui fled the city and arrived in the UK. That made him the latest addition to London’s growing contingent of protesters in exile—democracy activist Nathan Law has been the most prominent arrival so far. Their presence is adding another focal point to tensions between Britain and China.

When the UK returned Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty in 1997, after 150 years of colonial rule, it did so under the promise, enshrined in the Sino-British Joint Declaration, that it would enjoy special freedoms for 50 years under the “one country, two systems” model. These freedoms have eroded over time, but the UK never acted. That changed when China moved to impose a strict national security law in Hong Kong in response to last year’s sometimes violent anti-government protests.

In July, British foreign secretary Dominic Raab declared China’s new national security law a breach of the Joint Declaration, and announced plans to pave the way for millions of Hong Kongers to become citizens, a move that China quickly criticized as interference from a former colonial power.

UK businesses have also been caught in the crosshairs of the tensions over Hong Kong, especially financial services firms HSBC and Standard Chartered, which are based in the UK but conduct a major part of their business from the Asian financial hub.

Beyond Hong Kong, another human rights issue involving China started gaining traction. Reports of China’s detentions and repression of the Uyghurs, a Muslim minority that predominantly lives in its western region of Xinjiang, have surfaced since at least 2018, but it wasn’t an especially popular issue in Parliament, except among some human rights-oriented politicians.

Then in June, the Associated Press published allegations of a mass campaign of forced sterilization to depress the Uyghur birth rate in Xinjiang. At around the same time a video of men being rounded up at a train station believed to be in Xinjiang drew horrified attention in Britain and globally. China has admitted that camps for Uyghurs exist, but says they are a tool of de-radicalization for extremists, and denies allegations of forced sterilization or forced labor.

The situation prompted some lawmakers to seek ways to allow the UK to make a finding of genocide—a domain that has generally been the purview of the United Nations rather than individual states. In July, parliament’s upper house added an amendment to a trade bill to revoke or prevent deals with states preliminarily deemed by the UK High Court to be committing genocide. Changes to the bill are still being debated in the House of Lords before making its way back to the Commons.

The wind is also blowing against China among the public. In October, 74% of British respondents to a Pew Research survey had a negative view of China, compared to 16% in 2002. In fact, the Tories won in 2019 because they chipped away at the Labour Party’s so-called “Red Wall” of safely left-wing seats in the northeast of England. And for many of these voters, China matters.

In February 2020, the Tories ran an ad featuring a swing voter, David Barnard, explaining why he voted Conservative for the first time the previous year. In mid-July, when Westminster-based outlet Politics Home caught up with Barnard and asked him to evaluate Johnson’s first few months in office, he gave him a “B,” decrying the “silence” from the UK Government on the treatment of the Uyghurs in China.

“I would prefer to see Boris and the British government set an example and make a stand against that,” he said.

No V-shaped recovery for UK-China ties

But what Boris Johnson truly thinks of China remains a mystery—and that may be by design. You don’t lightly alienate the world’s second superpower—the one currently keeping the entire world economy afloat—in an age of Brexit. But Johnson also appears to have a personal affinity with China: As recently as June, he told Parliament that he is a “Sinophile” who believes “that we must continue to work with this great and rising power on climate change or trade or whatever it happens to be.”

But in addition to the tensions above, several possible flashpoints lie ahead.

The UK has invited India, South Korea, and Australia to join next year’s G7 summit, in an apparent attempt to form an alliance of democracies in China’s backyard. Considering that the Chinese tabloid Global Times called this “an outdated idea with Cold War mind-set,” it’s safe to say Beijing isn’t a fan.

Another area of tension will likely be the South China Sea, where the UK is scheduled to deploy an aircraft carrier, HMS Queen Elizabeth, next year. It’s a show of commitment to freedom of navigation in an area where multiple countries, chief of all China, have competing sovereignty claims.

On the economic front, the government is said to be reviewing supply chain dependency on China as part of the upcoming Integrated Review, an attempt to define the government’s national security and foreign policy aims.

Meanwhile, the China rebels will continue to pressure the government at every turn—pushing for a speech from the prime minister himself announcing a fundamental overhaul of the UK’s China policy, said Sam Armstrong, communications director for IPAC.

“The relationship has taken a turn for the worse in recent years,” echoed Tugendhat, “and there are many areas where we can still see that sadly, it has further to fall.”