These charts explain what’s behind America’s soaring college costs

The growing $1.1 trillion student debt burden in the US has been well documented, yet concerns are subdued. That’s because the burden, unlike the housing crisis, won’t cause a sudden economic crash. Instead, it will prompt a slow strangulation of spending spread over many years. Congress has made some minor efforts to reduce interest rates on debt, but the necessity for such large loans must be scrutinized. And that means confronting the indulgences of colleges.

The growing $1.1 trillion student debt burden in the US has been well documented, yet concerns are subdued. That’s because the burden, unlike the housing crisis, won’t cause a sudden economic crash. Instead, it will prompt a slow strangulation of spending spread over many years. Congress has made some minor efforts to reduce interest rates on debt, but the necessity for such large loans must be scrutinized. And that means confronting the indulgences of colleges.

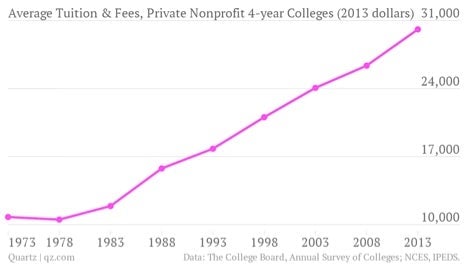

Tuition costs have soared in recent decades. In 1973, the average cost for tuition and fees at a private nonprofit college was $10,783, adjusted for 2013 dollars. Costs tripled over the ensuing 40 years, with the average jumping to $30,094 last year. Even in the last decade the increase was a staggering 25%.

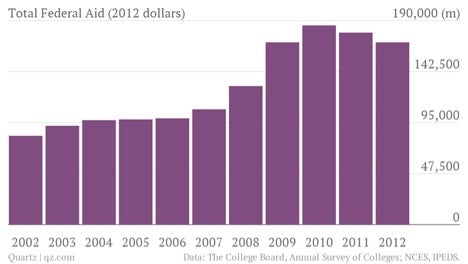

The ability of colleges to raise costs has been facilitated by a sharp increase in federal student aid. Lenders freely dispense credit to students, safe in the knowledge that all loans are guaranteed by the government. Between 1973 and 2012, federal aid (inflation-adjusted) increased more than 500%. Looking at a shorter period, between 2002 and 2012, total federal aid to students ballooned an inflation-adjusted 106% to $170 billion.

Colleges have effectively been guaranteed an income stream and have used that certainty to partake in an arms race against each other by constructing lavish facilities and inflating administrative processes. The pursuit of education has turned into a vicious circle in which students need bigger loans to pay for higher costs, and colleges charge higher costs because students are getting bigger loans.

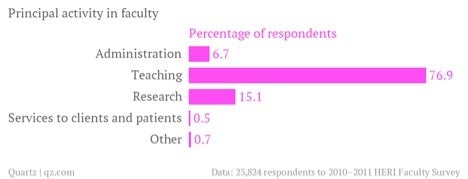

The apparent escalation in college bureaucracy may be reflected in changing patterns of teaching hours. A national survey conducted by the Higher Education Research Institute found in 2011 that 43.6% of full-time faculty members spent nine hours or more per week teaching (roughly a quarter of their time), which is a down from 56.5% in 2001 and a considerable decline from a high of 63.4% in 1991.

Notably, hours spent preparing for classes fell at a similar rate, while there was little change in time devoted to research. Administrative bloat fueled by excessive spending seems to be diminishing the focus on what college is supposed to be about, with the study showing that almost a quarter of professors at four-year universities do not consider teaching their “principal activity.”

Time spent teaching may be declining, but compensation for those at the top has increased sharply in recent years. Presidents are now paid like the CEOs of successful businesses, as evidenced by the Chronicle of Higher Education’s latest report. The findings showed that 180 presidents at private colleges earned more than $500,000 in 2011, compared with just 50 in 2004. Moreover, the top two highest paid presidents each received more than $3 million.

All this spending has been encouraged by a flawed student loan system that enables unwieldy inefficiencies. Today’s loan model was built with good intentions, tracing its roots back to Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society ambitions, but it was not designed for extended periods of stagnant wage growth and a widening gap in pay scales.

Education is more important than ever, with the comparative return on a degree still high relative to those without college qualifications. But to lower the costs of tuition, government support must be reduced. Lending institutions are too lax in giving out credit, knowing that the taxpayer will support 100% of defaulted loans. Without that firm safety net, lenders will be more discerning about borrowers’ fields of study; the expected income for a humanities graduate is not the same as an engineer. Less student aid will also make colleges think twice about their excesses.

Moreover, loans should not be an entitlement. There are too many colleges offering too many places to students. A study last year indicated that more likely to default than graduate, while about 40% of students have to take at least one remedial course during their studies, slowing their possible graduation date and increasing debts. These stats indicate that many students are not prepared or capable for college-level academics.

Both colleges and employers must embrace three-year bachelors degrees; the traditional four years is an arbitrary number that just extends the time in education. Institutions can also reduce costs by adapting to the modern age and offer more online learning. But they will only do this is if the government limits the ability of students to pay the prevailing high tuition costs.

The current model has inflated spending beyond the nation’s means, with colleges reaping the rewards while the government takes all the risks and graduates drown in debt. With an abrupt crisis unlikely, hard action may be delayed for years, allowing the noose to tighten on an already fragile economy.

We welcome your comments at [email protected].