Florent Crivello, the Parisian founder of virtual office startup Teamflow, is fond of saying that remote work is missing a certain je ne sais quoi.

He felt that acutely one day in 2018, when he had to handle a crisis as the head of a remote team. Crivello was a product manager for Uber Works at the time, and the platform had just suffered a major outage. He spent the day in a flurry of video calls trying to contain the chaos. By the time he logged off for the night, he was exhausted, alone, and felt like crying.

“I realized what made that moment so painful was the absence of presence,” Crivello said. Two years later—when the pandemic hit and many workers suddenly found themselves alone, exhausted, and on the edge of tears—he left Uber and founded Teamflow, a company created to help remote teams feel a sense of being together with their colleagues.

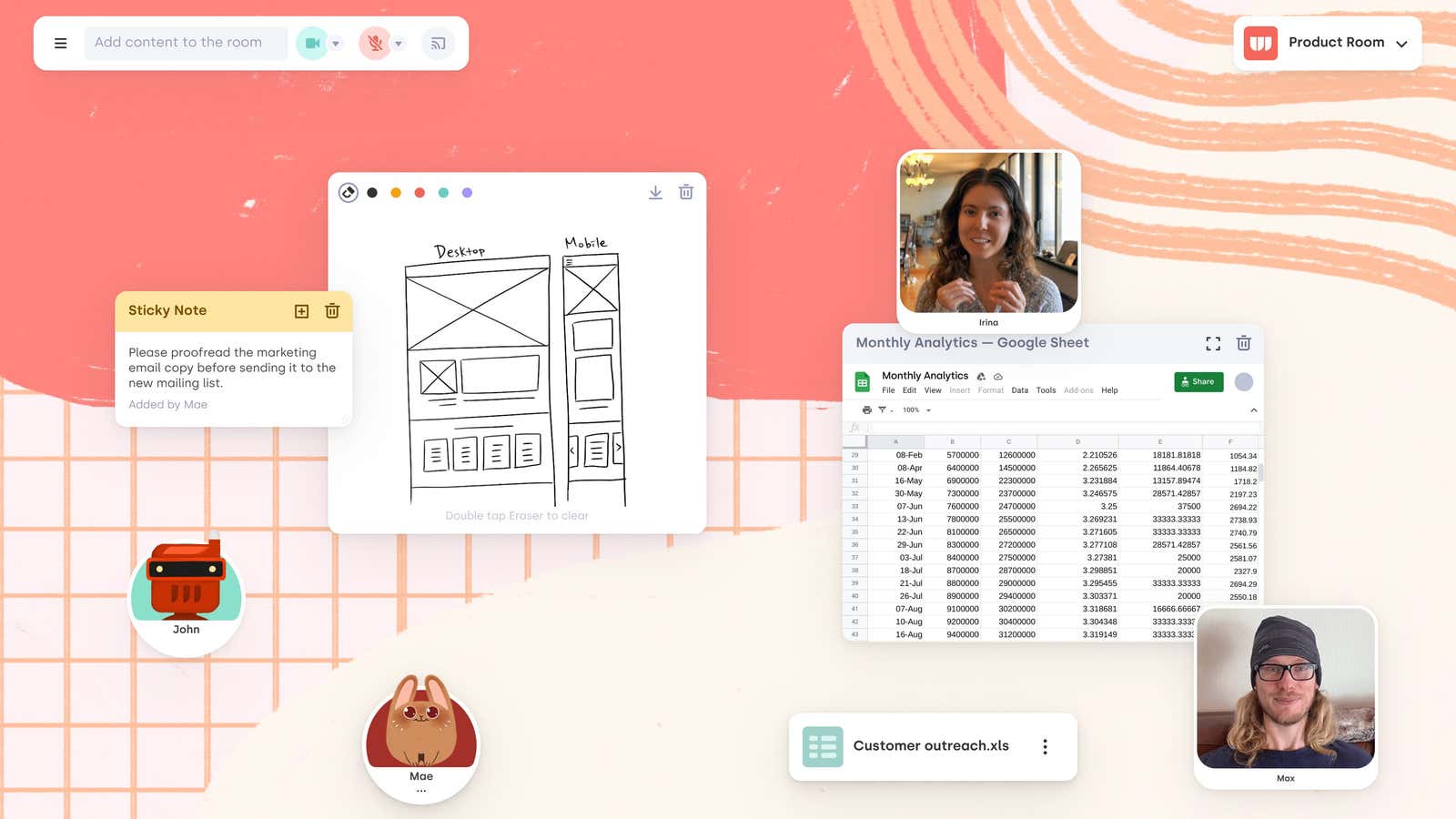

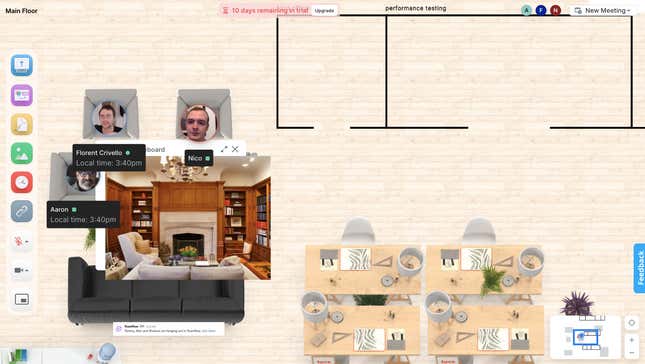

Teamflow sells virtual office space: a digital representation of a real office meant to recreate the most important interactions that typically happen in real life. Its aesthetic is minimalist, although Crivello says that may change over time. In the background, there’s a simple line drawing of a floor plan, peppered with a few illustrations of office furniture. Each worker is represented by a circle and can move around the space with their mouse or arrow keys. If a co-worker comes close enough, you can hear their voice and see their face in a video feed. As you talk, you and your colleagues can drag documents, images, links, and whiteboards onto the screen to illustrate your thoughts.

Teamflow is one of dozens of firms racing to develop a piece of software that can replicate the warmth and liveliness of real-life interactions. Whatever solutions they come up with could shape our working lives for a long time to come: Vaccine rollouts are delayed, as much as a fifth of the workforce in advanced economies is expected to stay remote beyond the pandemic, and the market for new remote collaboration tools is booming. Whether or not they succeed, each company is testing a different hypothesis for what the future of our working lives should look like.

There’s no reason to assume the working world will go on using the same old chat and video tools that existed before the pandemic, says organizational design consultant Sam Spurlin. When countries first went into lockdown, companies with a suddenly remote workforce rushed to adopt existing collaboration software as quickly as they could just to stay afloat. “I think a lot of organizations were in panic mode,” Spurlin said. “There’s going to be a point—and I think a lot of organizations have already hit that point—where they start to ask whether there’s actually a better way to work.”

Who needs offices?

Some virtual office startup founders argue that, if their products are successful, many white-collar knowledge workers will be ready to abandon physical offices for good.

Historically, the argument runs, there have been two reasons most companies need an office. First, they needed a centralized place where everyone could access shared, physical resources, like fax and copy machines, desktop computers, landline phones, and vast archives of paper records. Second, it’s easier for their workers to chat, collaborate, and build relationships with each other when they’re sitting in the same room. Those interactions are crucial, because management research has consistently shown that teams perform better when they communicate well, both in structured meetings and informal “water cooler” chatter.

Technology has already dispensed with the first need, the startups argue. “Today, with laptops and the cloud and Google Docs and Teams and all that, we’re realizing that you do not have to be at the office to be productive,” said Crivello. The massive pandemic-fueled shift to remote work has demonstrated that, for a large fraction of the workforce, that’s true.

Virtual office startups think their software is on the cusp of fulfilling the second need, by digitally recreating the social experience of working together in a physical space. When that happens, they say, the physical office—with all the associated evils of commute times, greenhouse emissions, and 9-to-5 grinding—will be obsolete. “Abandoning our outdated strategies around centralized offices and moving to a digital first world is fundamentally the right path forward for humanity,” wrote Chris Bourdon, founder of collaboration startup With, in a blogpost.

Real companies are just beginning to test that theory. Megumi Suzuki, the director of operations for a software testing startup that uses Teamflow, says the tool does make it easier to chat. “It’s better than something like Zoom that you have to schedule,” she said. “It just feels different…when you gather in a virtual office space like this, it’s more casual.”

Still, Suzuki said her co-workers don’t hang out in Teamflow all day long, which was the experience they missed about being in their physical office. More often, employees will hold “office hours” on Teamflow, a block of time when anyone is welcome to pop into the platform and chat with them. They also hold meetings on Teamflow, which gives co-workers the chance to linger afterward and split off into pairs or groups to gab.

Melissa Mazmanian, an associate professor with joint appointments in management and computer science at the University of California, Irvine, acknowledged the tools could be helpful for making remote teams feel more connected. But there are always going to be limits on how much a virtual office can do. “I don’t think these tools are ever going to fully replicate that kind of in-person dynamic,” she said. Whether or not they boost collaboration depends not just on the software, but how companies use it.

“I think we have to be careful about having one more thing to monitor, one more interruption, and one more place that you are virtually projecting competency and dedication,” she said. If companies don’t develop the right set of norms and expectations about using virtual offices, they could actually get in the way of getting work done.

A varied approach

Startups have taken a wide range of approaches to replicating the experience of working with colleagues in a physical office.

Some are very literal: Gather, for instance, builds painstakingly detailed fantasy offices pixel-by-pixel in a cheerful 8-bit aesthetic. Workers use arrow keys to control a customizable avatar, which they march to an open desk each morning to signal their arrival to work. When it’s time for a meeting, workers walk their avatars into a conference room; when they want to chat with a colleague, they head down the virtual hall to find that person at their desk.

All this fidelity to real-life office routines is meant to evoke the feeling of togetherness you get from working in the physical world. “We decided that the most accessible way to recreate that for people was to have this 2D parallel world where you could have some of the ritual of logging on, going into the office, and seeing who’s chatting in the common area or retreating to your desk,” said Gather client support specialist Lauren Strenger.

Other startups have taken a more abstract approach. “Trying to translate the physical world purely into a digital world doesn’t make sense,” said Bourdon, the With CEO. “We think the digital world can offer a lot of the same core interactions that you want without having to be literal about it.”

With makes no attempt to create a virtual replica of the physical office. The interface is more like a shared desktop, with circular avatars representing co-workers scattered across the screen. To replicate the dynamic of walking up to a co-worker’s desk to chat, With uses the same so-called “spatial audio” concept as Gather and Teamflow: Drag your circle next to a colleague’s circle and the two of you can see and hear each other.

Co-workers can drag documents, dashboards, and design tools into the shared desktop to work on them with their team. “It would be overly cumbersome to have to say, ‘I want to see a dashboard so I need to go across the physical space in my virtual world to go find it,’” Bourdon said.

There are no familiar rows of desks with digital colleagues sitting in them in the With world. But Bourdon hopes to recreate the feeling of colleagues’ virtual presence just by having their avatars sprinkled here and there across a shared screen. Each co-worker is represented by a drawing of an animal, which occasionally blinks its eyes to remind you there’s a real, living creature working behind its cartoon facade.

Another startup, Sneek, has broken office life down even further. It exists to recreate just one feature of in-person work: the act of glancing over at a colleague’s desk to see if they’re available to chat. To translate that experience into the digital world, Sneek will (with permission) take a photo from your computer’s webcam every few minutes and pop it into a Brady Bunch grid, along with snapshots of all your co-workers’ faces. If you want to talk to someone, you can check the grid to see if they look like they’re the middle of something or have set a “do not disturb” message. If not, you can click on their face and hop into a video call.

Going beyond reality

The startups, however, are not content to simply replicate life in the real world—many have aspirations to improve upon it. After all, virtual space isn’t bound by the same tedious limitations as physical space.

Consider the chaotic universe of Reslash. The startup offers a product that is, in some ways, similar to more conventional collaboration tools like With and Teamflow: You have an avatar, you can talk to people whose avatars are nearby, and you can add elements to a shared screen. But its philosophy is pure mayhem.

“What we wanted to do is, what if you can just destroy and create beautiful chaos out of nowhere?” said founder Ashwin Gupta. “As you’re creating that mess, you’re connecting with the people you’re creating that mess with.”

The aesthetic of Reslash borrows from campy corners of the internet. The room Gupta and I spoke in had a vaporwave vibe and oozed music from a “Cyberpunk 2077 Radio Mix” on YouTube. Gupta’s dream is that people will load their shared screens with gifs, images, games, and links, and that the tumultuous, overlapping, nonlinear mess they create will unleash their creative id in a way that wouldn’t be possible in a drab conference room.

Meanwhile, Around has built its videoconferencing tool’s value proposition around being less realistic than its competitors. Around compresses the traditional video grid boxes into small circles for each of the participants’ faces, and pushes them to the side of the screen so you can fill most of your desktop with the thing you’re actually working on. It also offers filters that reduce the quality of your video feed just enough that colleagues can still make out your expressions, but they can’t really tell if you’re having a bad hair day or your room is a mess in the background.

“This industry assumed that what people want is high-fidelity, high-definition video as close to real life as possible,” said Around CEO Dominik Zane. “But we’re spending a lot more time in video calls. So we started asking, ‘Is it still true that you want to take up the entire screen with high-resolution full HD video? Do you actually feel good in that?’”

Around is also attempting to lay the groundwork for a return to hybrid offices. Normally, hybrid team members experience meetings quite differently: Remote workers see a wide shot of the conference room where their in-person colleagues are gathering, giving the impression of being on the outside looking in, while in-person workers split their attention between the people sitting around them and a screen off to the side displaying a grid of their remote colleagues’ faces.

Around hopes to put hybrid meeting participants on more equal footing. Its software can pick out the faces of in-person co-workers arranged around a conference table and give each its own circle, meaning they’ll display on the screen exactly like remote participants do. It also developed a tool that allows multiple people to be on a video call in the same room without creating ear-splitting echoes—meaning in-person workers can all participate from their own laptops, just like remote workers.

If these startups are right, the future may include significantly fewer offices, more seamlessly integrated hybrid workplaces, and new generations of workers who go their whole careers without commuting. Spurlin, the organizational consultant, mused that future waves of remote work tools will probably drift ever further from the familiar features of office life, just as the icons for smartphone apps gradually started looking less and less like physical objects and early automobiles eventually stopped looking like horse-drawn carriages.

“Eventually, there will be people who have only ever done the remote work thing,” he said, “so having a tool that simulates standing up in your cubicle is going to be real weird—a version of having to explain to someone why the save icon is a little floppy disk when they’ve never seen one before.”