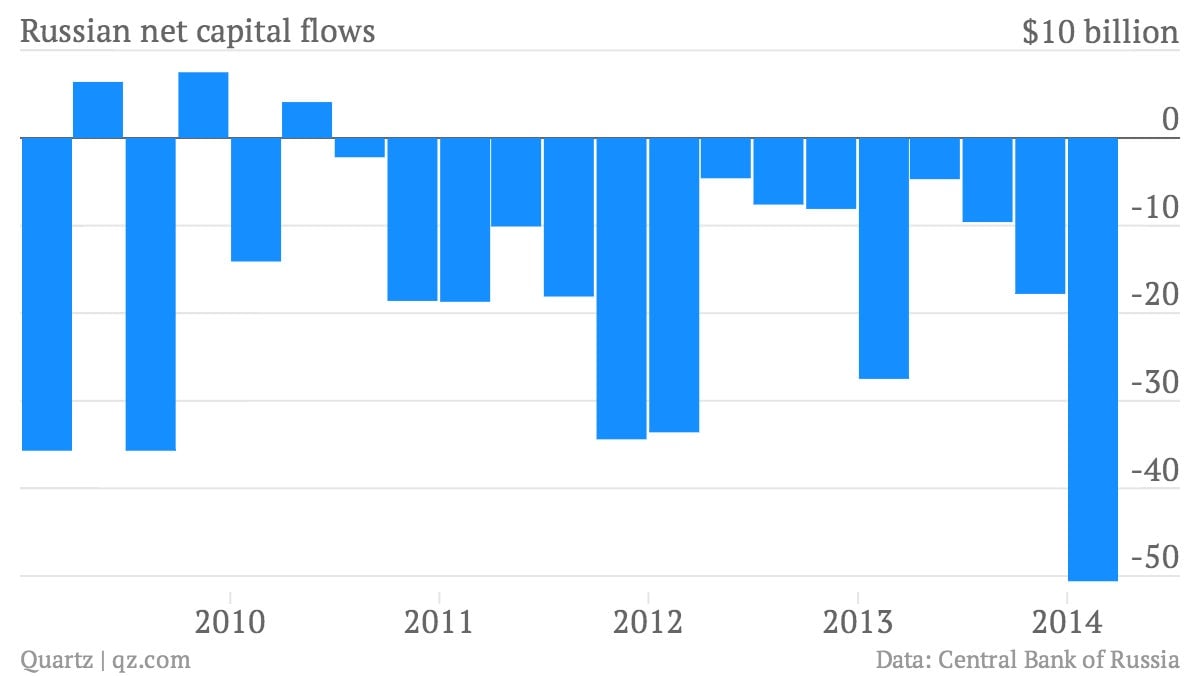

Putin’s Crimea caper is pushing billions of dollars out of the Russian economy

Nearly $51 billion in capital coursed out of Russia during the first quarter as president Vladimir Putin embarked on his Crimean adventure, according to data from the Russian Central Bank. That’s the biggest quarterly outflow from the country since the fourth quarter of 2008, when the global financial crisis was getting into full swing.

Nearly $51 billion in capital coursed out of Russia during the first quarter as president Vladimir Putin embarked on his Crimean adventure, according to data from the Russian Central Bank. That’s the biggest quarterly outflow from the country since the fourth quarter of 2008, when the global financial crisis was getting into full swing.

Russia’s officials now say that roughly $100 billion will leave the country this year, up from a previous estimate of $25 billion. For Russia, the outflow of capital is not a dire situation. That’s because it has loads of foreign reserves and runs regular—although diminishing—foreign account surpluses. (In other words, it’s a net lender of capital to the world, not a borrower.)

But while it’s not a crisis, it is a problem. That’s because capital outflows weaken the currency. And a weaker currency adds to inflation, or prompts the central bank to raise interest rates, or both. Either way the result is a headwind impeding economic growth.

Oh, and don’t forget, the Ukraine story isn’t over yet. Just this morning, Ukraine cut off Russian energy giant Gazprom from its customers in Europe, by “temporarily” stopping the purchase and storage of Russian gas that runs through Ukrainian pipelines to Western Europe. With Russia relying on energy exports for half its state budget, the outflow of capital might pinch a bit more than usual.