Can WhatsApp stop spreading misinformation without compromising encryption?

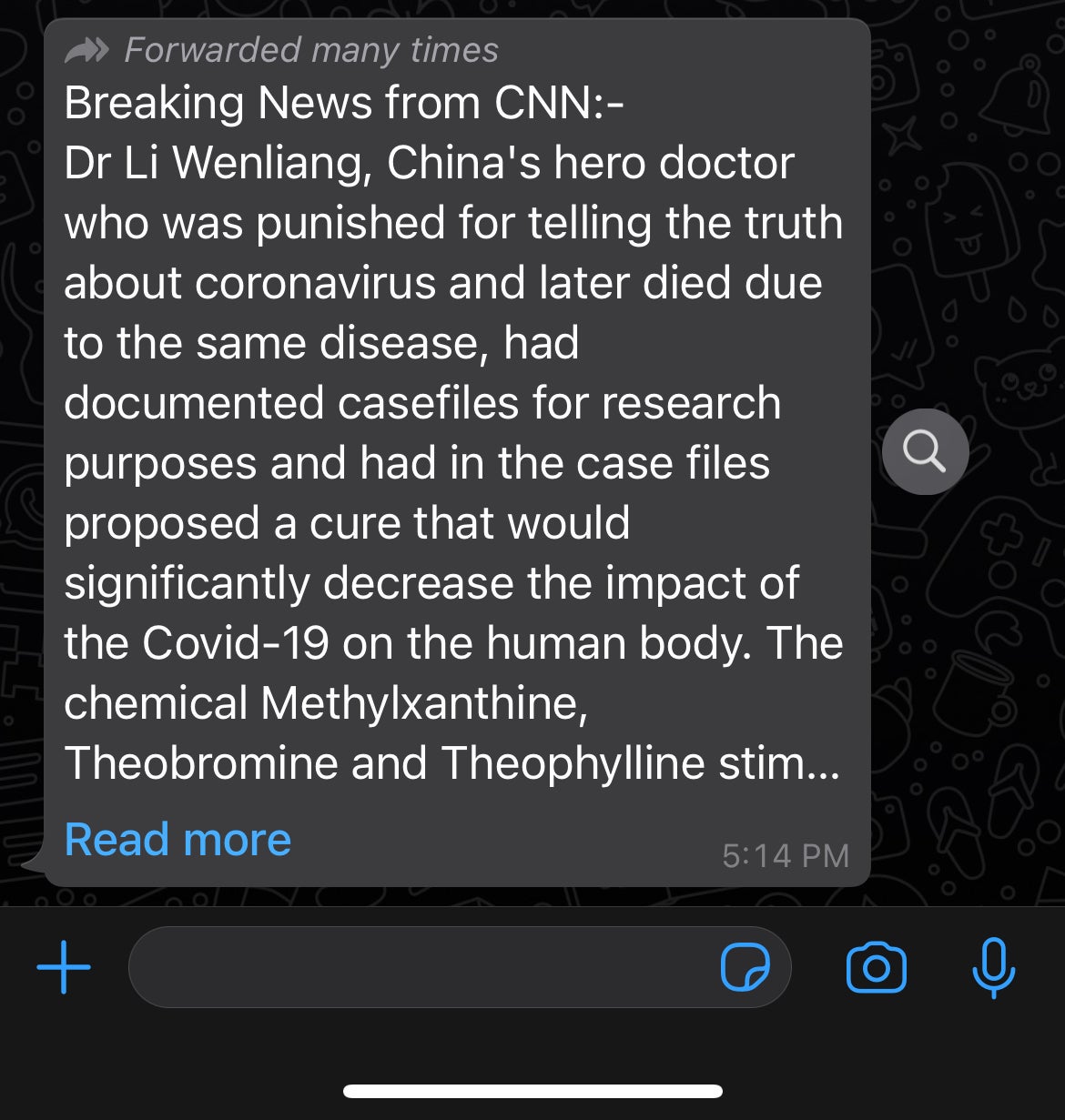

On a jaunt through the darker corners of the internet, a conspiracy-minded reader might come across a fake news story claiming that 5G cell towers spread Covid-19. Alarmed, he sends the story to his family WhatsApp group. A cousin forwards it to a few of her friends, and one of them forwards it to a group of 200 people dedicated to sharing local news. As the lie gains traction, WhatsApp helps it reach more people more quickly—but the app’s managers have no way of knowing.

On a jaunt through the darker corners of the internet, a conspiracy-minded reader might come across a fake news story claiming that 5G cell towers spread Covid-19. Alarmed, he sends the story to his family WhatsApp group. A cousin forwards it to a few of her friends, and one of them forwards it to a group of 200 people dedicated to sharing local news. As the lie gains traction, WhatsApp helps it reach more people more quickly—but the app’s managers have no way of knowing.

WhatsApp, the Facebook-owned messaging platform used by 2 billion people largely in the global south, has become a particularly troublesome vector for misinformation. The core of the problem is its use of end-to-end encryption, a security measure that garbles users’ messages while they travel from one phone to another so that no one other than the sender and the recipient can read them.

Encryption is a crucial privacy protection, but it also prevents WhatsApp from going as far as many of its peers to moderate misinformation. The app has taken some steps to limit the spread of viral messages, but some researchers and fact-checkers argue it should do more, while privacy purists worry the solutions will compromise users’ private conversations. As every social network does battle against the spread of viral lies, WhatsApp faces its own impossible choice: Protect user privacy at all costs, or go all in on curbing the spread of misinformation.

What is encryption?

Digital encryption grew out of military efforts to create uncrackable secret codes, which date back at least as far as the Spartans. In the modern era, government scientists working with top secret clearances dominated the field until the 1970s, when computers started to gain commercial use. Among the earliest private sector adopters were banks, which needed a secure way to transmit financial information.

Consumer-facing encrypted messaging began in earnest in the 1990s, with the development of the Pretty Good Privacy protocol, which formed the backbone of early private-messaging software. The much more secure Signal protocol—which powers the open-source encrypted messaging app of the same name—was developed in 2014. WhatsApp gave users the options to send messages using Signal encryption that year, and made it standard for all messages in 2016. Facebook added an optional encryption feature soon after, and in 2018 Google announced all conversations on its Android messenger would be encrypted.

Encryption is a key privacy protection, and ensures that WhatsApp is one of the few remaining places on the Internet where you can communicate without being snooped on by big businesses or governments. Activists and dissidents living under repressive regimes rely on encryption to communicate freely. But it also makes the conversations that happen in WhatsApp impossible to moderate.

Unlike Facebook and Twitter, which have redoubled their efforts to use algorithms and human fact-checkers to flag, hide, or delete the most harmful viral lies that spread on their platforms, WhatsApp can’t see a single word of its users’ messages. That means misinformation about politics, the pandemic, and Covid-19 vaccines spread with little resistance, raising vaccine hesitancy, reducing compliance with public health measures like social distancing, and sparking several mob attacks and lynchings.

What is WhatsApp doing about misinformation?

WhatsApp has already taken some steps to curb misinformation without eroding encryption—but its options are limited. In April 2020, WhatsApp began slowing the spread of “highly forwarded messages,” the smartphone equivalent of 1990s chain emails. If a message has already been forwarded five times, you can only forward it to one person or group at a time.

WhatsApp claims that simple design tweak cut the spread of viral messages by 70%, and fact-checkers have cautiously cheered the change. But considering that all messages are encrypted, it’s impossible to know how much of an impact the cut had on misinformation, as opposed to more benign content like activist organizing or memes. Researchers who joined and monitored several hundred WhatsApp groups in Brazil, India, and Indonesia found that limiting message forwarding slows down viral misinformation, but doesn’t necessarily limit how far the messages eventually spread.

WhatsApp also now affixes a magnifying glass icon to highly forwarded messages, which signals to the recipient that this is not an original missive from their friend but a viral message that has been ricocheting around the web. Users can tap the magnifying glass to quickly google the content of the message. But that puts the onus on people to do their own fact-checking, when they might be more inclined to trust information coming from a friend or family member.

Could WhatsApp fact-check messages?

Currently, fact-checking anything on WhatsApp is extremely labor-intensive. A handful of media outlets and nonprofits have set up tip lines, where users can forward any message they suspect might contain misinformation. Journalists on the other end of the line check out the claim and manually respond to each person with their findings, encouraging the recipient to pass on the fact-check to whoever sent them the message in the first place.

“They have pretty limited reach,” says Kiran Garimella, a postdoctoral fellow at MIT who studies WhatsApp misinformation. “Not a lot of people are aware of them. There’s also the supply side: Journalists cannot scale, so if a million people suddenly start sending their tips, it’s a very labor-intensive process and they cannot do this at scale.”

Garimella and others have called on WhatsApp to make more drastic changes, including enabling “on-device fact-checking.” They say WhatsApp could put together a list of known misinformation posts that are going viral in a given moment. Since WhatsApp can’t read anyone’s messages, they might base this list on the debunked messages users have sent to fact-checking tip lines, or the most popular lies spreading on Facebook or Twitter. (There is considerable cross-pollination between misinformation on WhatsApp and other platforms.)

Then, WhatsApp could send this “most wanted” list out to every user’s phone. When a user sends or receives a message, their phone would check it against the constantly updated list of viral misinformation, and warn the user if there’s a match. In this way, proponents argue, WhatsApp can flag at least some false content without snooping on users’ conversations.

“Guaranteeing the privacy of the users is as important as combating misinformation,” Garimella and colleagues wrote in an article for the Harvard Kennedy School’s Misinformation Review. “In our understanding, both can coexist in parallel…our objective is to provide a middle-ground solution which could satisfy those who request actions in combat of misinformation spreading in such platforms, but also keep the privacy of the users’ phone before it is encrypted.”

So far, the idea has met fierce resistance from online privacy advocates like the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), who argue that it would undermine encryption and amount to an unacceptable assault on digital freedoms. “It’s simply not end-to-end encryption if a company’s software is sitting on one of the ‘ends’ silently looking over your shoulder and pre-filtering all the messages you send,” the organization wrote in a blog post.

Protecting encryption

This isn’t just a semantic argument, says EFF strategy director Danny O’Brien. Even the smallest erosion of encryption protections gives Facebook a toehold to begin scanning messages in a way that could later be abused, and protecting the sanctity of encryption is worth giving up a potential tool for curbing misinformation. “This is a consequence of a secure internet,” O’Brien says. “Dealing with the consequences of that is going to be a much more positive step than dealing with the consequences of an internet where no one is secure and no one is private.”

Still, others are holding out hope for a middle path that can bring automatic fact-checking to WhatsApp without trading away too much privacy. WhatsApp might give users a chance to opt out of fact-checking or let them decide which organizations they get fact checks from, suggests Scott Hale, an associate professor of computer science at Oxford.

“My vision for misinformation would be more like antivirus software,” Hale wrote in an email. “I choose to use it; if it detects a virus it alerts me and does nothing without my express permission. Like antivirus software, I would ideally have a choice about what (if any) provider to use.”

No matter what WhatsApp does, it will have to contend with dueling constituencies: the privacy hawks who see the app’s encryption as its most important feature, and the fact-checkers who are desperate for more tools to curb the spread of misinformation on a platform that counts a quarter of the globe among its users. Whatever Facebook decides will have widespread consequences in a world witnessing the simultaneous rise of fatal lies and techno-authoritarianism.