Dear India, here’s how to cope with a censored internet, xoxo China

India’s internet is gradually heading in the direction of China’s.

India’s internet is gradually heading in the direction of China’s.

In February, the Indian government announced sweeping restrictions on social media platforms that require the firms to more quickly take down posts the authorities deem offensive, to hire Indian grievance officers to handle complaints, and to identify the “first originator” of contentious messages. The new guidelines were released following a standoff between the government and Twitter, which refused to block accounts posting about the country’s farmers’ protests, and come into effect from today (May 26).

If companies don’t comply with new rules, they face losing protections under Indian law that are similar to those conferred under Section 230 in the US, which prevent platforms for being prosecuted over content they host.

WhatsApp sued the Indian government today (May 26) over the new rules, Reuters reported, which the company argues are unconstitutional and a breach of citizens’ right to privacy. It’s particularly opposed to the “traceability” requirement of identifying the user behind a message, which would require breaking encryption. Its parent, Facebook, has said it aims to comply with the provisions of the rules, while continuing discussions with the government around them, while Google has also said it is working to comply with local laws.

Last year, the Modi government already took a leaf out of China’s playbook, blocking several Chinese apps, including TikTok, on the grounds that they engaged in activities “prejudicial to sovereignty and integrity of India.”

While bans on foreign platforms may not be imminent as some news reports suggest, the new restrictions are stoking fears that online news and dissent will be increasingly stifled. In China, as similar rules came into play, foreign social media platforms departed or were blocked, leading to the rise of Chinese platforms whose terms of agreement make clear that user communications will be shared with the government in many circumstances.

As a result, internet users in China have long had practice circumventing their authorities’ watchful eyes. It might just be time for users in India—or anywhere really—to draw some valuable tips from their experience.

Use homophones or coded language

The initial stage of censorship in China focused on censoring keywords related to sensitive topics, which meant that as long as one used homophones for “sensitive” words, they could continue to discuss those topics.

For example, some users used “GCD”or “GD” to refer to the Chinese Communist Party, whose pinyin (or transliteration) is Gong Chan Dang, to criticize the regime online. But because Beijing requires internet service providers to store users’ IP addresses for 180 days, as well as forcing users to register platforms using real identities, it is easy for authorities to locate and arrest those making offensive remarks online no matter what techniques they use to avoid censorship, said Eric Liu, a former censor at China’s Twitter-like Weibo, who is now based in the US where he advocates for internet freedom.

“When will India require internet users to access platforms using their real names just as in China…I will keep a close eye on that,” said Liu.

Still, such scrutiny hasn’t stopped users from continuing to invent coded approaches—there are dozens of them for the Tiananmen crackdown alone.

Last year during the peak of the coronavirus, many users used codes, including “Martian” language based on popular ancient Chinese characters, to preserve a censored article that recorded a Wuhan doctor’s account of being warned by hospital authorities to not to spread information about the coronavirus, to document Beijing’s early efforts in suppressing information about the outbreak. Other approaches people used to preserve the article include writing the story backward, in emojis, or even in braille.

Chinese users have also used punctuation to separate each character in sensitive terms to avoid censorship, according to a young web sleuth surnamed Wang who has compiled a Google spreadsheet to record instances where Beijing punishes people for making online and offline remarks critical of the government or social issues.

Or they turn to history: Wang said posting about famous incidents that took place in China’s ancient times and that are similar to some of Beijing’s actions is another way to criticize the regime.

Use VPNs when you want to critique the government

While users in India can access most major foreign services smoothly, China’s users have long relied on the virtual private network to get on the platforms as Beijing has blocked the websites to control information. But it might still be necessary for Indian users to use VPNs when they criticize the government, as the tool can help them hide their IP address to prevent them from being traced by authorities.

Screenshot for posterity

Many in China have developed a habit of taking screenshots of comments or posts that they think could be censored, as content is now being deleted at a faster pace with Chinese tech companies’ increasingly sophisticated combination of automated techniques and human censors. Moreover, some have shared screen recordings of censored posts with others to avoid scrutiny on Chinese messaging apps such as WeChat, as these apps are usually pretty good at censoring text and pictures, but not videos. Users often post screenshots of the deleted post to their own accounts to spread the information.

Give it a spin

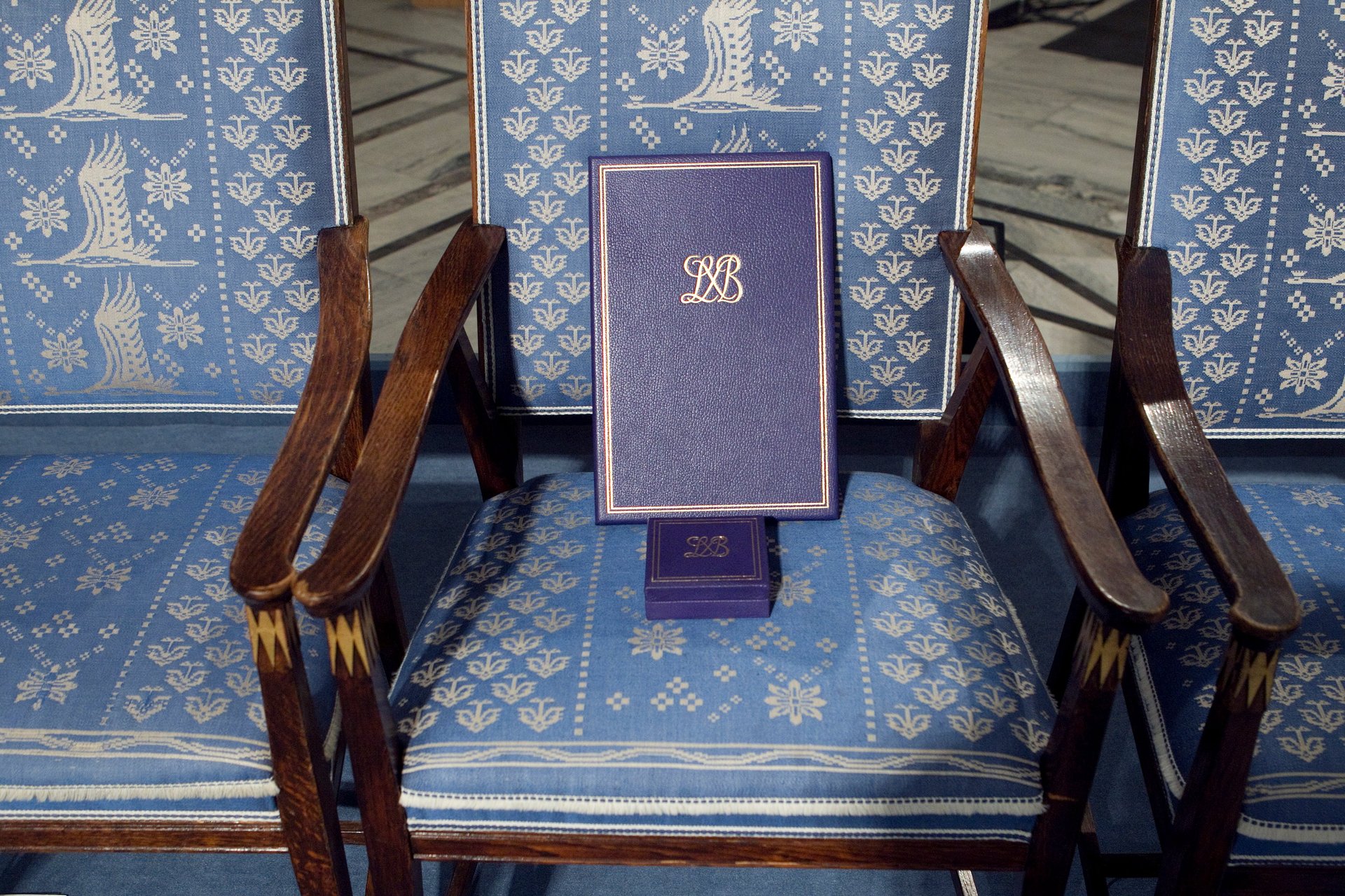

In chats, people sometimes refer to topics with sensitive images that have come to be synonymous with a person or event—such as the famous empty chair that symbolized Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo due to his absence at the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony. But even these can be filtered and censored, leading to a rather garbled conversation.

Photoshopping skills can help.

When China censored mentions of the #MeToo movement, some users decided to share a university student’s censored letter by posting images of it upside down. This finding was proven by Citizen Lab, a Canada-based research institute regularly examines how Chinese censorship works. The lab found that by mirroring or rotating an image; changing the aspect ratio of an image, such as by stretching the image to be wider or taller; or blurring a photo can effectively help an image escape WeChat’s censorship algorithm. Other approaches include adding a sufficiently large border to the smallest version of an image, or creating a complex pattern such as duplicating the same image multiple times in a single photo.