The Biden administration is trying to decide if China is a rival or partner when it comes to climate change. This week, US officials seemed to switch between the two positions.

On April 18, US climate envoy John Kerry and his Chinese peer Xie Zhenhua released a statement saying the two countries are “committed to cooperating” on the climate crisis. The next day, Energy secretary Jennifer Granholm said in a virtual panel that the US should seize more control of renewable energy supply chains, many of which are dominated by China, and that it isn’t worth sacrificing worker safety and human rights on “the alter of low costs.” Also on April 19, Secretary of State Antony Blinken clearly framed China as a rival to be overcome: “It’s difficult to imagine the United States winning the long-term strategic competition with China if we cannot lead the renewable energy revolution,” he said in a speech. “Right now, we’re falling behind.”

For now, the only answer for the US appears to be treating China as a bit of both. But the US will need to choose its economic battles carefully or risk slowing the pace of the energy transition—something it can no longer afford to do without failing its international commitments.

How the US should compete with China on clean energy

As Blinken articulated in his speech, China currently dominates the global clean energy market, as the leading producer and consumer of solar panels, batteries, and electric vehicles. It also controls the production of key raw materials needed for clean tech, including lithium, rare earth metals, and copper. With low labor costs and economies of scale already established in China, US companies are unlikely to catch up as competitors in bulk manufacturing of today’s clean energy technologies, said Joanna Lewis, an environmental economist at Georgetown University who studies US-China trade. Tariffs on imported solar panels implemented by the Trump administration in 2018, for example, proved to offer scant benefit for US competitors.

“Blinken’s speech almost sort of ceded wind and solar to China,” Lewis said. “Rather than competing with China on tech that was invented decades ago, it’s wise to be forward-thinking about the tech we’ll need down the road.”

Lewis argues the US should focus on two things: innovation and R&D, particularly in next-generation technologies like green hydrogen or advanced geothermal, and green jobs in marketing and physically installing hardware for energy transition. Rather than trying to compete for low-value steps in the supply chain, such as pollution-prone mining of raw materials, the US can incentivize domestic demand for green technologies that play to America’s competitive strengths in distribution and retail.

“You need somebody to sell and install the cheap solar panel from China, and that’s where you can actually capture a lot of the revenue,” she said. “And, these are higher value-added, skilled jobs.”

Playing defense against China’s command of low-cost manufacturing is a losing game, agrees Fan Dai, director of the California-China Climate Institute at the University of California, Berkeley. “I don’t think the US should do anything because it wants to compete with China,” she said. ”The real question is how to recognize our strengths and weaknesses, and where the US needs outside resources and should take advantage of what China can offer.”

Unacknowledged elephants in the room

In the short term, there are political advantages to both countries in broadly aligning their climate agendas: It plays well domestically, and could help put pressure on India, Australia, Canada, and other big emitters to step up their ambitions for Biden’s upcoming Earth Day climate summit. But unresolved tensions in the energy market are still liable to boil over later on.

The Kerry-Zhenhua agreement highlighted a few discrete areas for collaboration and policy alignment such as non-CO2 emissions like methane and hydroflourocarbons, and airline and marine emissions. The agreement is also pointedly framed as “multilateral,” rather than solely between the two countries, Dai said, to make clear that it’s part of the larger Paris Agreement process and to separate it from other areas, like the status of Hong Kong, where the two countries remain at odds.

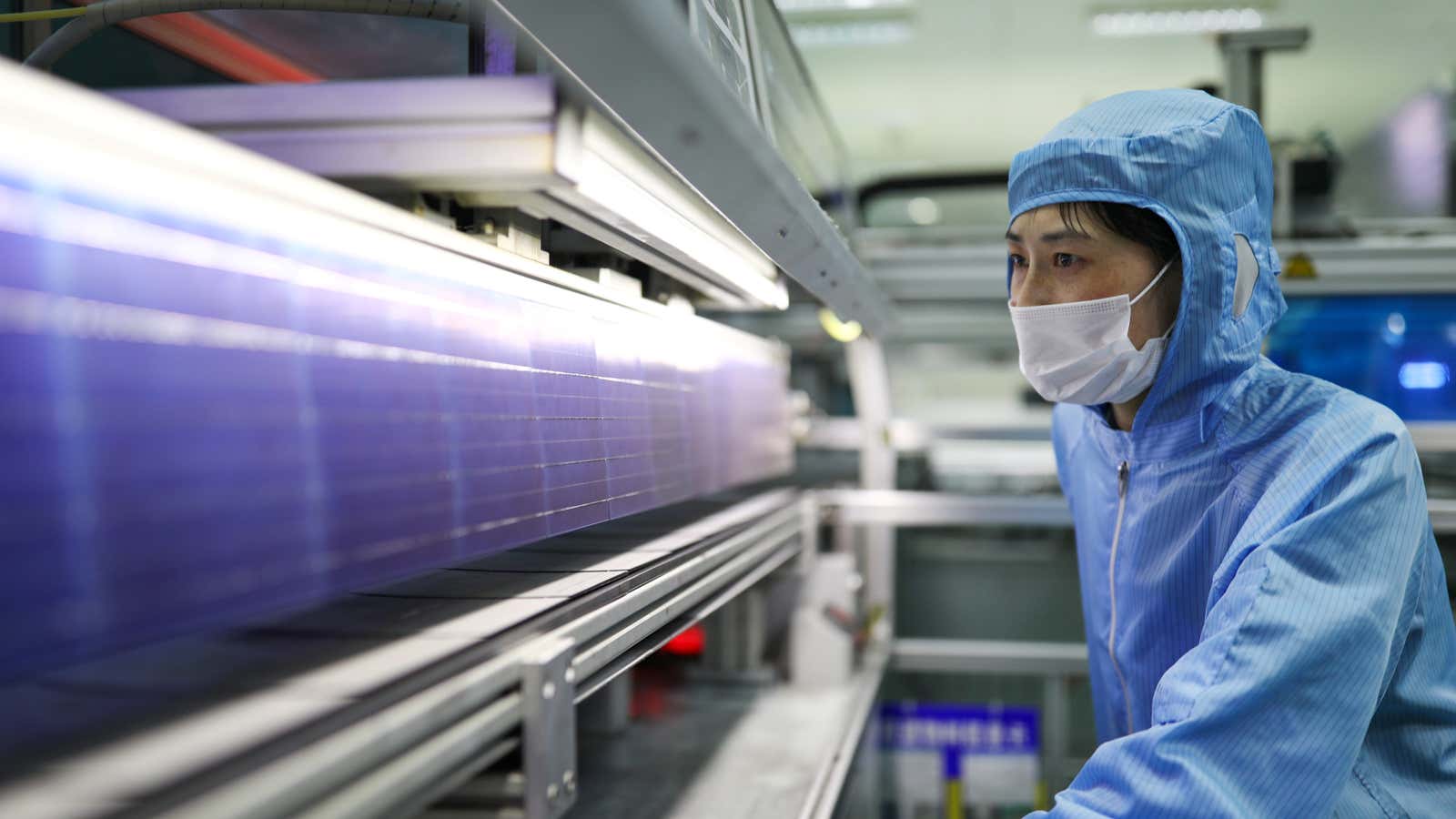

None of this, however, addresses the elephants in the room: China’s ongoing push to build more coal-fired power plants at home and abroad, clean tech intellectual property infringement, and human rights abuses at Chinese solar panel factories. The latter in particular could blur the convenient firewall between climate and other social issues, if US solar companies face heightened consumer scrutiny of their Chinese supply chains or see their costs rise as they seek out labor-friendly suppliers.

From Biden’s presidential campaign to his rollout of a $2 trillion infrastructure package before Congress, Biden has consistently framed climate action as an imperative for US job creation. That may well be true—but trade protectionism is a risky strategy for the clean energy industry, which relies on global supply chains. Ultimately, the US will likely find it easier to hit its goal to decarbonize the electric grid by 2035 if it can continue to count on China to cut the costs of producing the materials needed to do so. But China’s emerging lead on technologies like 5G and artificial intelligence are a warning that the US can’t take its advantages in innovation for granted. For the US, “winning” the clean energy race is as much a matter of funding university research departments and jobs training programs as it is building factories.

“It doesn’t make sense for every country to manufacture its own solar panels,” Lewis said. “This real challenge is finding a way for everyone to benefit from green jobs, but still recognizing that there are global efficiencies, so so we can scale them as quickly as possible.”