People who need remittances the most have to pay the most to send them

People in Sub-Saharan Africa rely heavily on remittances—money that migrant workers abroad send home. But the region loses almost $2 billion in remittances every year to charges from banks, post offices, and other financial intermediaries, more than any other region in the world, according to a new report (pdf) by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

People in Sub-Saharan Africa rely heavily on remittances—money that migrant workers abroad send home. But the region loses almost $2 billion in remittances every year to charges from banks, post offices, and other financial intermediaries, more than any other region in the world, according to a new report (pdf) by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

Last year total remittances to sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) were about $32 billion and accounted for about 2% of regional GDP. That money may become even more critical as foreign aid to the region continues to drop. Globally, migrant workers already send three times as much money to developing countries as foreign governments do.

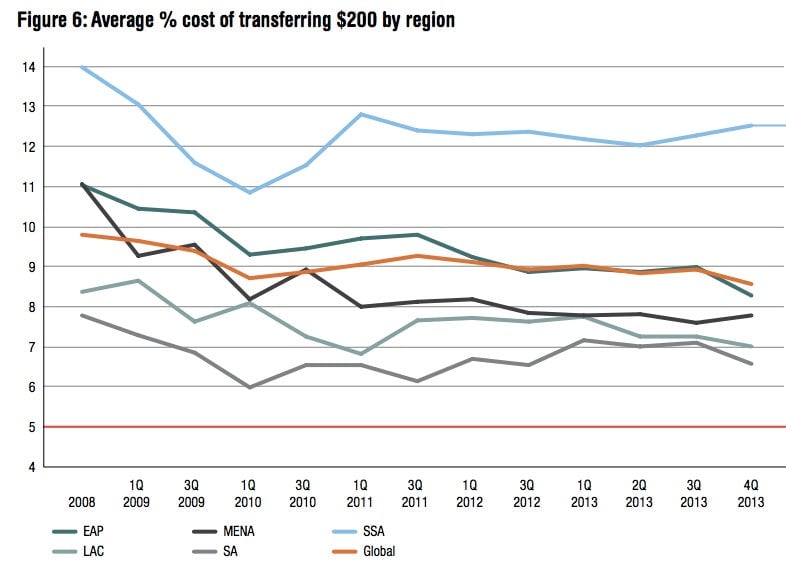

The average migrant worker from sub-Saharan Africa has to spend about $25 to send $200 back home. Workers from the UK or France pay approximately $20, and in the US, just $12. Africa’s diaspora pays twice as much as migrant workers from South Asia, another major remittance market, to send money home. On average, Africans pay around 12.3%, compared with the global rate of 7.2%, of their remittances when sending funds back home. And remittance charges in Africa have been rising since 2010:

It’s hard to know exactly why fees are so much higher in Africa, ODI’s report says, since remittance services aren’t transparent about their costs. One factor, though, is a lack of competition: In about half of Sub-Saharan countries, two firms, Western Union and MoneyGram, control more than half the locations at which remittances are received. Cumbersome financial regulation, anti-money-laundering provisions, and the fact that not many people have formal bank accounts could also contribute to higher costs, despite the spread of mobile phone banking.