Wikipedia is better than Google at tracking flu trends

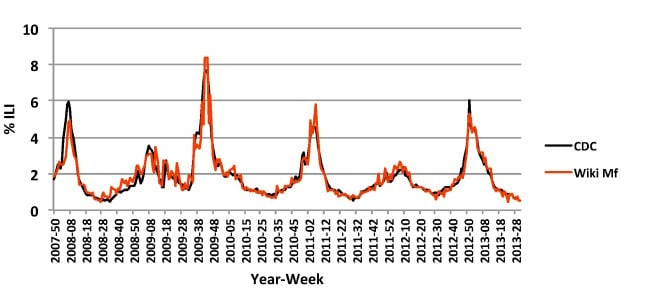

Wikipedia traffic could be used to provide realtime tracking of flu cases, according to a study published today. John Brownstein, a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and director of Boston Children’s Hospital’s computational epidemiology group, along with follow researcher David McIver, has developed an algorithm for pulling daily flu metrics from data on which flu-related terms are viewed in the online open-source encyclopedia.

Wikipedia traffic could be used to provide realtime tracking of flu cases, according to a study published today. John Brownstein, a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and director of Boston Children’s Hospital’s computational epidemiology group, along with follow researcher David McIver, has developed an algorithm for pulling daily flu metrics from data on which flu-related terms are viewed in the online open-source encyclopedia.

Brownstein previously developed Flu Near You, which relies on users to self-report flu-like symptoms in themselves, family, and friends. But by analyzing page views for terms such as ”fever,” “influenza,” and “Tamiflu,” for example—Brownstein and McIver created a more reliable method of estimating flu spikes.

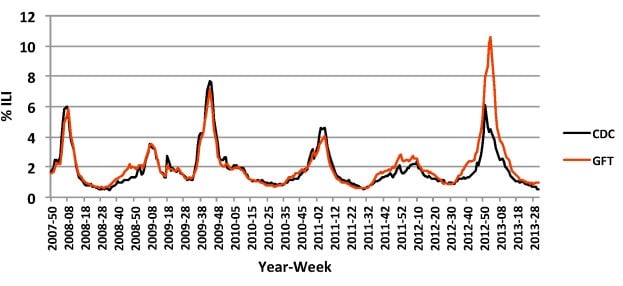

Using online activity to monitor flu trends isn’t a new idea. Google Flu Trends has used flu-related search engine queries to estimate the number of daily cases since 2008. But the algorithm failed in 2009, overestimating the peak number of cases during the H1N1 swine flu pandemic. The 2012-2013 flu season saw similar miscalculation.

When compared to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the prevalence of flu-like illnesses in the US (which is released to the public with a two-week lag) the Wikipedia model was found to be more accurate than Google’s. As the charts below show, that’s because of its ability to stay on track even during sudden spikes in infection (and the accompanying panic):

Perhaps, the authors suggest, hyped pandemics and particularly unpleasant flu strains cause increased Googling—including by those not ill but looking for news stories. The researchers didn’t investigate exactly why those who click through to Wikipedia are more likely suffering from the flu, or near someone who’s suffering. But it stands to reason that the site can give researchers a nuanced read on how we’re feeling: Wikipedia is likely to be among the top results in web searches—and as the No.1 source of health information on the internet, those who click through to the site may be more likely to be seeking information about symptoms or medications.

In the paper, Brownstein and McIver point out that the CDC’s data isn’t perfect, either: It’s reported by physicians, who may be more likely to log flu-like symptoms when they have heard media buzz about a possible pandemic. Indeed, it’s not impossible that web-driven metrics may one day overtake the official data in both speed and accuracy.