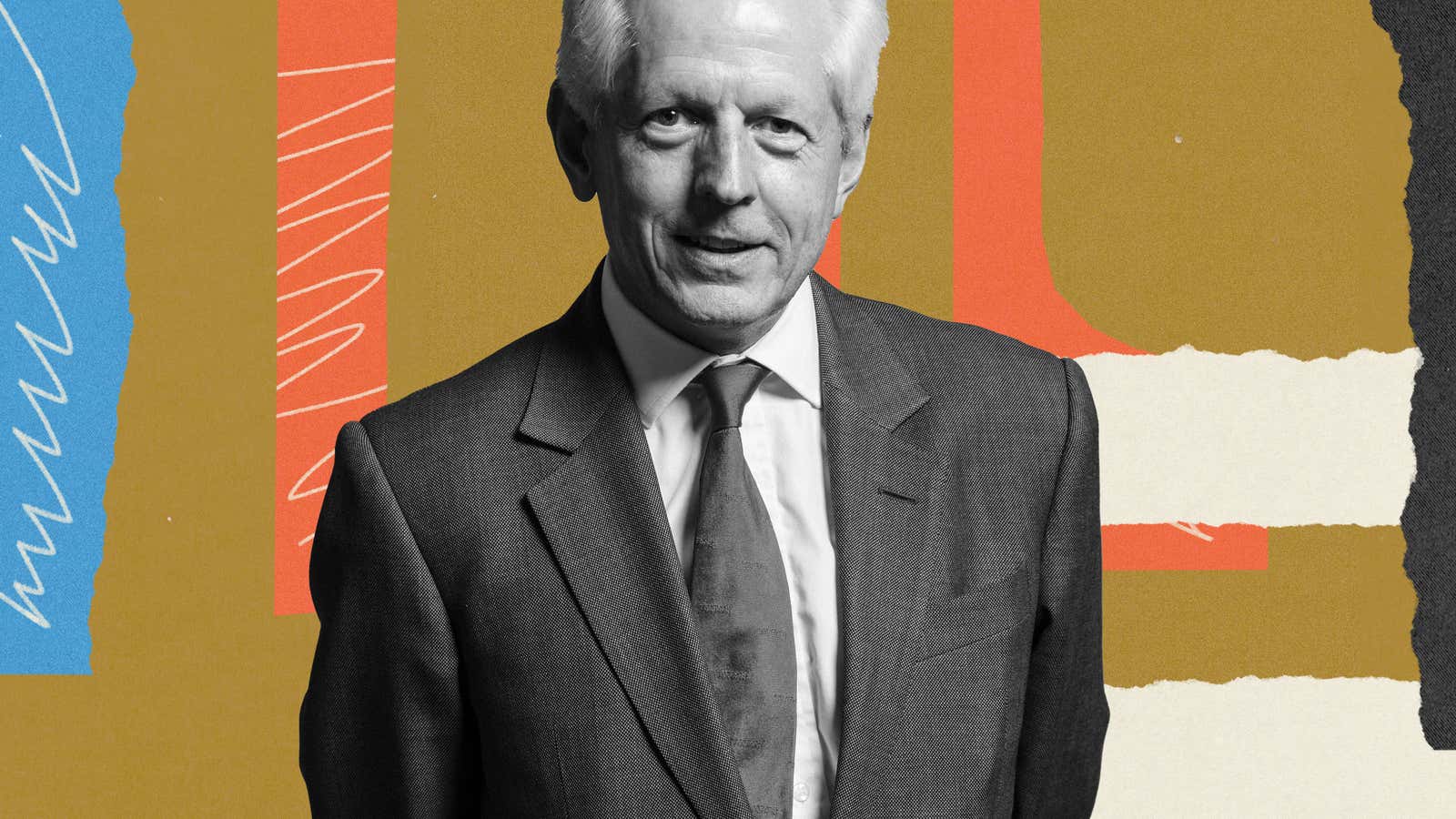

Richard Graham has been a member of Parliament since 2010. He is chair of the All Party Parliamentary China Group (APPCG), founded more than 20 years ago to “ensure parliamentarians are kept well informed on China.”

Graham has lived and worked in and around China for 40 years. In the early 1990s he was British trade commissioner to China, and later first secretary at the British embassy in Beijing, and consul for Macau. He is now the prime minister’s trade envoy for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and for Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

Graham is a former director of the Great Britain China Center and accompanied former UK prime ministers David Cameron and Theresa May to China. He speaks Tagalog, Bahasa Indonesia, Malay, Cantonese, and Mandarin.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Graham: It’s a day that started with yet another UK-China incident.

Quartz: Yes. How do you feel about the fact that several of your colleagues were sanctioned by the Chinese last night?

Graham: I don’t think it’s a clever move by China because it doesn’t achieve anything. None of those individuals have got properties in China, and I’m not sure any of them have been there for a long while. All of them will wear it as a badge of honor. The sanctions [China] put on the members of the European Parliament have probably blown up the possibility of the EU-China investment agreement being approved. And in our Parliament, whatever anyone’s individual thoughts on what Tom [Tugendhat], Nus [Ghani], and others have said, the perception of an authoritarian state trying to close down elected voices is not a good one.

From a Chinese perspective, you’re just encouraging a drift towards a sort of cold war. Every time either side does anything there’s an immediate response. And we need to get to a place where people don’t always need to react. I tried to explain this before to the Chinese, that in a democracy, parliamentarians are elected [and] we respect the right of people to have their views and to say them. That is a key difference between us.

Were you opposed to the initial coordinated sanctions imposed on Xinjiang officials by the UK, US, EU, and Canada?

Graham: It’s not what I would have been advocating because I could have anticipated what the [Chinese] response would be, but it’s very difficult. As a general rule, I do think [we should do] everything we can to try and ratchet down tension at a time when, because of the pandemic, people are not easily able to sit around a table and talk about these issues and defuse them. It’s arguable whether [the sanctions] in the longer term will make a difference, either in Xinjiang, or to improve the relationships between people, and encourage China to be closer with the democratic world.

It reminds me of something that happened to you in 2014 when you were denied a visa to Hong Kong.

Graham: You’re right. I’d called for a [House of Commons] debate on what was happening in Hong Kong [during the umbrella movement] 1. There were over a million people on the streets. Out of courtesy I let the Hong Kong Economic Trade Office and the Chinese embassy know. The Chinese embassy dispatched their number two to our party conference in Manchester to try and dissuade me on the basis that this would be bad for relations between our countries. I explained to them that if we were going to debate these issues, I thought it was important that it was led by somebody who knew what they were talking about. Their way of responding was to ban me—three days before the delegation was due to go—from going on this UK-China Leadership Forum2.

We assembled an emergency meeting of all those who were going. And I said to them, ‘You’ve got two options: You can either accept that the Chinese can veto who comes to these forums or you can stick up for the principle that neither side interferes with the other’s team.’ So we said to the Chinese, ‘We will cancel the forum,’ which I think surprised [them]. But we’ve never had that problem since.

And then, in fact, when [Chinese president] Xi Jinping came to London about six months later [on a state visit to the UK], as chair of the APPCG, [I had] the honor of receiving him and his wife to Parliament. The Chinese embassy rang me up beforehand to say, ‘Please don’t mention the visa problem to Chairman Xi’—as if I would. And later on that visit, at the Guildhall banquet, one of their ministers apologized to me and said it wouldn’t happen again.

What was president Xi like?

Graham: I wouldn’t pretend to know Xi Jinping at all. He’s quite hard to read.

When I was introducing other members of the House of Commons and the House of Lords to him, he was fascinated to meet Michael Dobbs, author of the book House of Cards, which [Dobbs] gave him a signed first edition of, because he’d just been over on the West Coast of America and seen the set for the American [Netflix show]House of Cards. That sparked a sign of recognition and interest.

There are some family links with the UK. It’s a country that he is interested in, not least because the Communist Party has always been interested in that question of what was the glue in [UK] society that somehow held everything together during Victorian times? Part of the answer is probably religion, and that’s a difficult one for the CCP.

What are some of the memories that stand out to you about your time in China?

Graham: My eldest son was born in Hong Kong. My youngest son was born in Shanghai, the first British baby born there since 1949, and our daughter in between was born in London. All three of them were with us in Shanghai. So it’s been a mixture of experiences—some very happy moments, individually and family-wise, and some great people who I worked with both as a diplomat and as a businessman. One particular highlight was helping create a charity called Care for Children, which was the first foster care program in China. It’s had an extraordinary impact on quite a lot of children’s lives.

Everything is exciting about China. And I think one of the dangers of the discourse at the moment is that some of my colleagues leave the impression, unwittingly, that the whole of China is a Communist Party apparatus rather than just a billion people who are trying to live their lives, grow up, be educated, fall in love, have children, have jobs that are worthwhile, climb mountains, and all the rest of it, just like everybody else. They happen to live under a political system that’s very different from ours.

You are one of the few MPs who has been to Xinjiang. Can you tell me about the experience?

Graham: All the peripheries of China are so different and they weren’t always part of China. They’ve got their own languages, customs, culture, and in some cases religions. The challenge has always been, how do you incorporate the peripheries into one central united nation? The values in the PRC’s Constitution are very strong about respecting those cultures, languages, religions and so on, but the reality on the ground can be very different.

I spent a lot of time in Xinjiang in 1993 [crossing the Taklamakan Desert] and then on two separate visits with my wife. There were already, and I think there always have been, tensions between Han Chinese and Uyghurs in Xinjiang. That got much worse after the terrorist incidents [of 2009] and then very much worse again after 2016.

My last trip there was in 2016, when I took an APPCG delegation there in order to see what was happening. Urumqi 3 was under a virtual police state—armored cars on streets, heavily armed Chinese police and in some cases People’s Liberation Army, the markets closed down, very obvious CCTV on the entrances to mosques, and Uyghurs sitting or standing in a very silent, sullen, resentful way. There was no evidence of the wonderful life that used to be there, at the traditional market in Kashgar, for example. This was not a happy situation.

The US says that what’s happening in Xinjiang is a genocide. The gulf between an ‘unhappy situation’ and a genocide is quite large. What exactly do you think is happening in Xinjiang?

Graham: I don’t think we have enough evidence personally for a claim of genocide to be sustained and that’s the UK government’s view, too. But I don’t think it’s necessarily for an individual country to make that assertion without a huge amount more evidence.

When I said it was an unhappy state, I don’t mean that word lightly. There are a large number of education centers or extended prison camps. Some of them were there a long time ago. We saw one in the Taklamakan desert in 1993. But that whole program has been vastly extended. And all the tools of artificial intelligence to monitor and interfere with people’s lives have been extended since then.

I accept the Chinese argument that there were and are real reasons to be concerned about Uyghur involvement in Islamic extremism, that numbers of them were in Syria with Islamic fundamentalists, that there is a nascent independence movement, and that there were these incidents at the railway station, which caused real angst. In an authoritarian state that brooks no dissent, clearly that security challenge was going to be met in a very rigorous, if not brutal way. But things have gone way beyond that. The real question for China is, as things become known, and they will do sooner or later, how comfortable will their own people be with the sort of abuses that are very likely to have been committed?

You’re seen by your more hawkish peers as an apologist for the Chinese government. How do you feel about it?

Graham: There are some people, both within Parliament and without, who would like to try and deploy me as the person representing the Chinese point of view against some colleagues representing the anti-China point of view. For me, this has never been about being pro- or anti-China. It’s about being pro-Britain and our national interest. But my way of explaining our national interest is much wider than just human rights.

I think it is interesting that some of the loudest, most assertively anti-China voices are not those who’ve been there and understand what’s happening. That intellectual curiosity that most MPs have very strongly is intense when you go over to China. Those who’ve been over there and understand the complexities are less likely to be quite so definitive in their judgments.

Your approach to China strikes me as similar to the one pioneered under the ‘golden era’ 4 of relations. Is that fair?

Graham: Actually, I wasn’t a fan of the golden era language, because as I said to George at the time, where do you go from the golden era? There’s only one way, which is down.

Osborne was trying to attract a lot of investment at a time when our finances were in dire straits. And it worked up to a point. But we were very shy in seeking market access for British services in China.

George found my approach to China rather hawkish. Now, of course, the mood from a lot of the Conservative Party is that I’m not nearly hawkish enough. I’ve been absolutely consistent for the last 40 years about my belief that we should engage with China, that there are lots of opportunities for Britain and there are some risks.

What do you think will happen to the UK-China relationship in the coming years?

Graham: The sooner we get back to engaging, the better. I’d be happy for them to come over here and engage, too. After quite a long period of nonphysical contact, the first formal meetings will be pretty agonizing. There will be, I have no doubt, tea and a lecture on Xinjiang or Hong Kong. Anyone who has lived and worked in China knows you have to go through that. Our way of responding has to be different than just reciprocating with more of the same.

I don’t think anything is predetermined. We assume that the world is sliding into a cold war, let alone a hot war, and that therefore we’re all swept along on this tide of inevitability—no. It is up to us to do things that make all those unpleasant things much less likely.