The technology that lets deaf people hear could also treat hearing damage

When someone’s auditory nerve is damaged, a cochlear implant acts as a substitute for the lack of vital nerve cells. But one day, it turns out, the implants could help those cells regrow. Gary Housley, director of the Translational Neuroscience Facility at the University of New South Wales, has published a study (paywall) demonstrating the process in animal models.

When someone’s auditory nerve is damaged, a cochlear implant acts as a substitute for the lack of vital nerve cells. But one day, it turns out, the implants could help those cells regrow. Gary Housley, director of the Translational Neuroscience Facility at the University of New South Wales, has published a study (paywall) demonstrating the process in animal models.

A standard cochlear implant works by picking up sound in an external microphone, processing it on a tiny computer that rests behind the ear, and then transmitting it to a surgically implanted receiver that converts the sound to electrical pulses. These signals are sent to different regions of the auditory nerve, allowing the deaf to experience a representation of sounds around them. But while these allow a deaf person to understand speech without lipreading, pitch perception remains poor, and the sounds aren’t lifelike (you can listen to an approximation of them here).

But after five years of development, Housley and his colleagues have tweaked a cochlear implant to deliver an effective treatment for deafness as well.

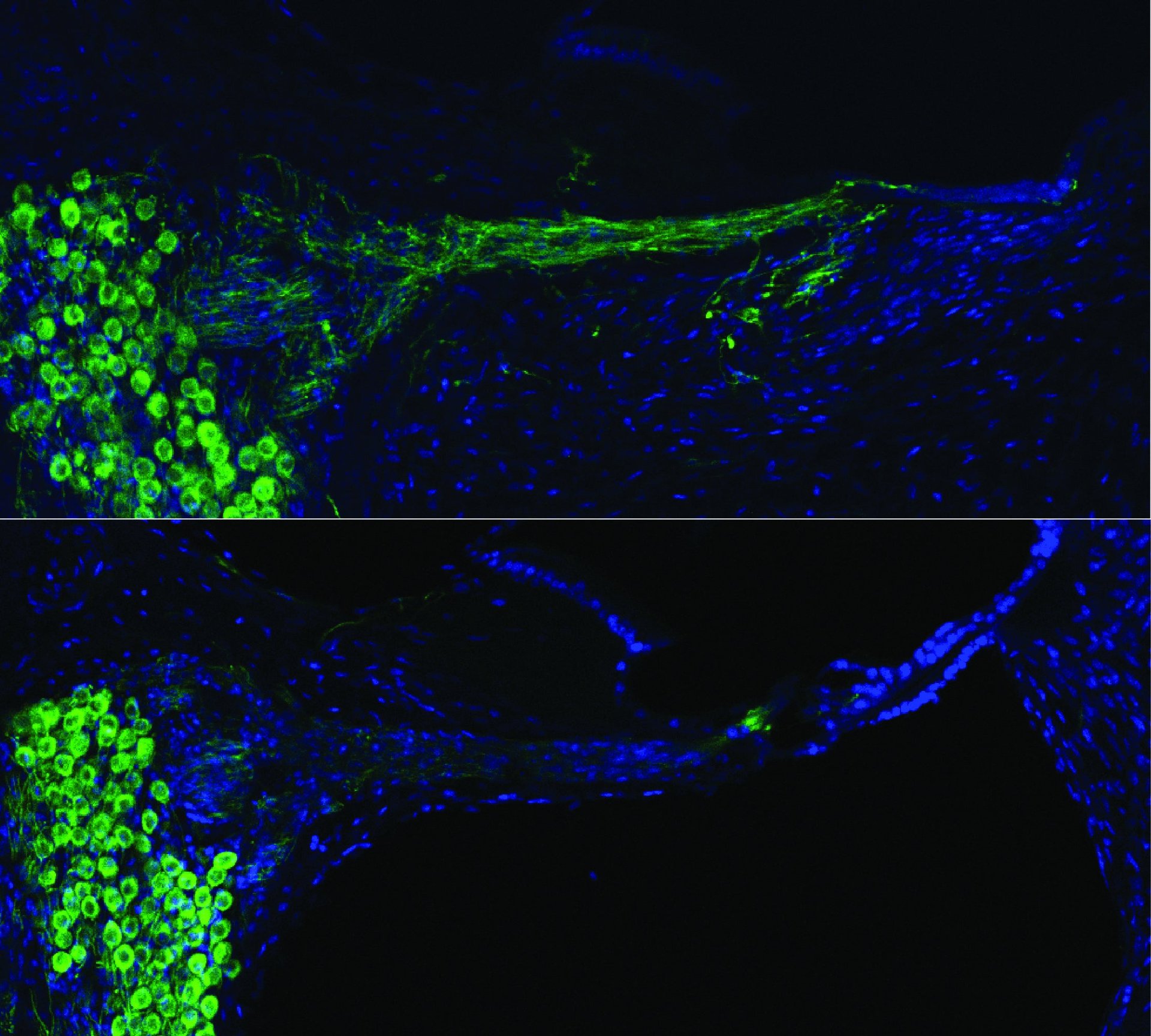

Neuroscientists have known for a while that a damaged auditory nerve can be regenerated with the help of proteins called neurotrophins, which are vital for the growth and survival of neurons. But getting the neurotrophins to the places in the nerve where they’re needed has posed a problem. A cochlear implant, though, goes to just those places. “No-one had tried to use the cochlear implant itself for gene therapy,” Housley said in a press release. “With our technique, the cochlear implant can be very effective for this.”

During the procedure to place the implant, Housley and his colleagues injected a solution of DNA into the ear and delivered a few electrical pulses to trigger its transfer into surrounding nerve cells. This stimulated neurotrophin production for several months, and would add only minutes to the initial procedure. While this won’t end deafness (and in fact will only help people whose hearing has been damaged or has declined with age, not people with congenital deafness) Housley hopes it will allow people who use cochlear implants to hear a lot better, with a broader range of sound and pitch.