Politics are coming for the “apolitical” Olympics

The 2020 Summer Olympics begin later this month in Japan, a year behind schedule, and mired in controversy as the city of Tokyo enters a state of emergency due to rising Covid-19 cases.

The 2020 Summer Olympics begin later this month in Japan, a year behind schedule, and mired in controversy as the city of Tokyo enters a state of emergency due to rising Covid-19 cases.

It’s been a rough 18 months for elite athletes, who have trained in between lockdowns and will now compete for medals in empty stadiums. But the Games aren’t just the opportunity of a lifetime—they’re also a unique platform that have given athletes the chance to advocate for issues like mental health and racial equality.

If they choose to do so in Tokyo this year, they will face the censure of Olympic organizers, who have long fought to keep the Games “apolitical.” But that notion is being seriously tested today by two distinct trends: the newfound power of individual athletes, and the growing public pressure for accountability over issues like human rights and environmental impact in awarding the Games to host cities.

Between this year’s Games and next year’s Winter Olympics in Beijing, it’s likely the issue will come to a head.

“Right now, the Olympics are experiencing their most serious crisis in decades,” argues Jules Boykoff, chair of the department of politics and government at Pacific University in Oregon. How Olympic bodies deal with it “will determine the future of the Games—if there is to be one.”

Why are the Olympics apolitical?

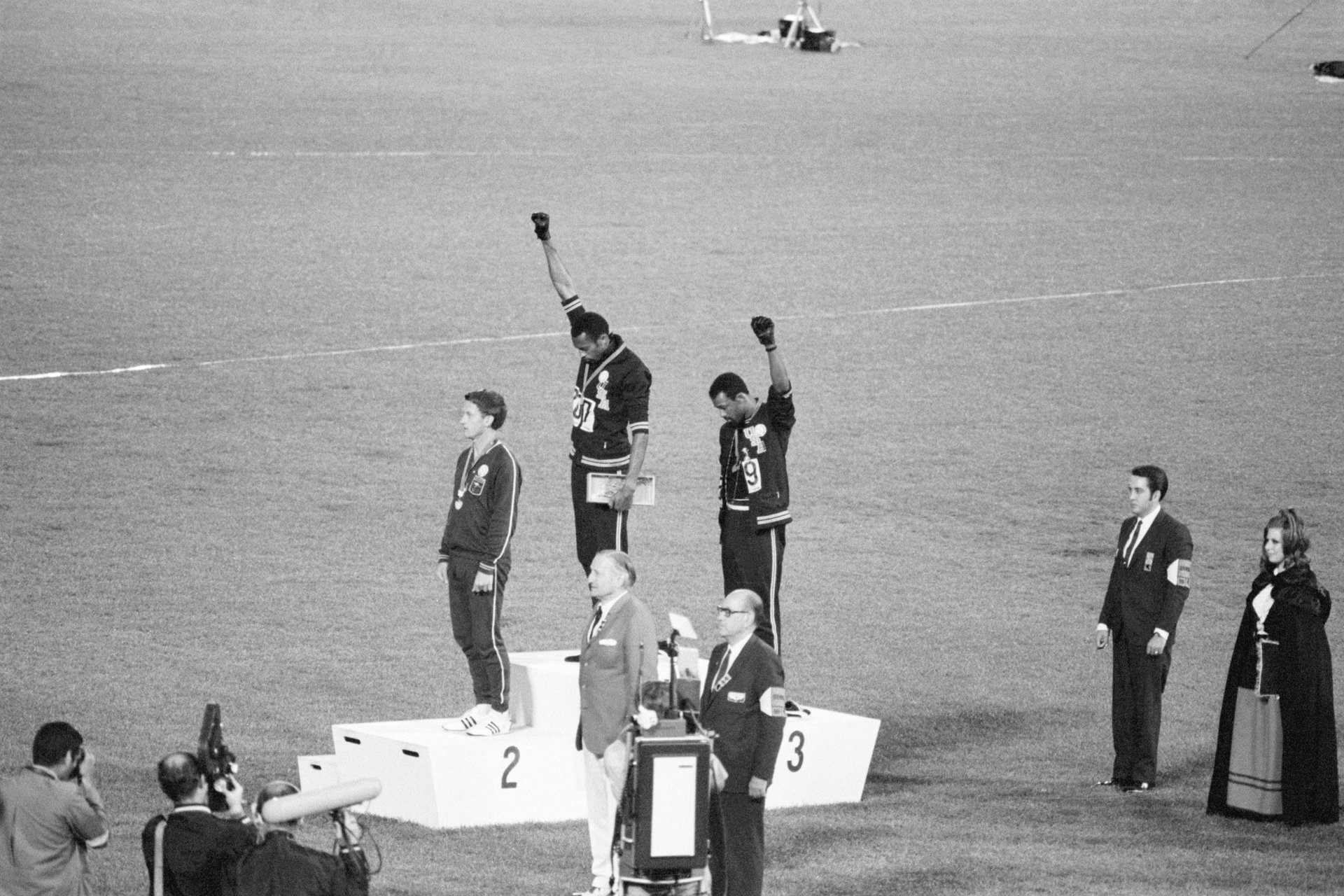

In 1968, Martin Luther King was assassinated, and towns and cities in the US burned as Black Americans protested police violence, poverty, and systemic racism. The US Olympic team was in Mexico City for the Summer Games. It’s there that two Black US athletes made one of the most significant acts of political protest in modern sports history.

After John Carlos and Tommie Smith won bronze and gold medals in the men’s 200-meter sprint, they stepped onto the podium, and as the US national anthem played, they raised their black-glove-clad fists in a Black Power salute. The audience booed; Carlos and Smith were kicked off the US team and given two days to leave Mexico.

These athletes’ Olympic careers ended 50 years ago because the Games have always had a “quixotic notion that they’re apolitical,” says Boykoff. In fact, getting kicked off the team for taking a stand was not unheard of for much of the Olympics’ modern history. The official reason is that acts of political protests may distract from the sport and other athletes’ victory, and can challenge the Olympic movement’s mission of “promoting peace and development through sport.”

Every four years for the past 125 years (interrupted only by two world wars), it has been the responsibility of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to ensure that up to 11,000 athletes from more than 200 countries or territories gather in one place to compete in 15 to 46 different sports. (The Winter Olympics began in 1921 and the Paralympics in 1960.) That’s a whole lot of different nationalities, religions, political beliefs, and governance systems in one place—and a lot can go wrong. Hence the principle of political neutrality, codified in Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter (pdf, p. 90), which bans all kinds of “demonstration or political, religious, or racial propaganda…in any Olympic sites, venues, or other areas.”

The IOC believes that only by remaining neutral can the Olympics survive the test of time. But the idea that the Games are apolitical has always been “fiction,” says Barbara Keys, a professor of international history at Durham University—both because and in spite of the IOC.

The IOC hosted the Summer Olympics in Berlin in 1936 under a Nazi government that banned some Jewish athletes from competing. (A Black American athlete, the legendary Jesse Owens, scored four gold medals under Hitler’s nose.) Avery Brundage, who led the IOC between 1952 and 1972, opposed a US boycott of the “Nazi” Olympics, arguing that “the politics of a nation is of no concern to the International Olympic Committee.”

The Olympics, in fact, have always been a political platform. The US and the Soviet Union boycotted each others’ Games during the Cold War; in fact, according to Nicholas Evan Sarantakes, author of Dropping the Torch: Jimmy Carter, the Olympic Boycott, and the Cold War, half of all Summer Games have been boycotted by one country or another. The Games themselves can even be a catalyst for international incidents. At the Munich Games in 1972, Palestinian militants murdered 11 members of the Israeli team. In 1987, before Seoul was set to host the Summer Olympics, North Korean agents blew up a plane, killing more than 100 people. (The goal, one of them later said, was to cause fear ahead of the Games.)

So, while the Games are apolitical on paper, in real life they are just as messy and complex as the outside world. Still, athletes have faced consequences in the past for expressing political views. Now, the walls of political neutrality that the Olympic movement has built to insulate the Games from the outside world are coming down.

The power of athlete activism

In 2016, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick spent each pre-game national anthem kneeling to protest racism and police killings of Black Americans. He paid a substantial professional and personal price for it, but ignited a wave of athlete activism that has since spread beyond American football to challenge even the Olympic movement.

As an institution, the IOC has taken the position that “when an individual makes their grievances, however legitimate, more important than the feelings of their competitors, and the competition itself, the unity and harmony as well as the celebration of sport and human accomplishment are diminished.” In a recent update to Rule 50 (pdf), the IOC Athletes’ Commission made it clear that kneeling, raising one’s fist, or wearing armbands featuring political slogans at the Tokyo Olympics would be a violation of Rule 50 and result in “disciplinary action…on a case-by-case basis.” (Athletes can “express their opinions…during press conferences and interviews, at team meetings, [and] on digital or traditional media.”) Since punishments for violating Rule 50 are the responsibility of the athlete’s National Olympic Committee, the international governing body for their sport, and the IOC, this could lead to situations where various institutions officially disagree about whether political protest is acceptable or not.

That’s not going to stop some athletes, who, thanks to endorsements and the power of social media, are “relatively financially insulated,” according to Boykoff, and “don’t need the Olympics as much as the Olympics need them.” For others, even if their livelihood is at stake, the Olympics could still be a platform for protest.

Qualifying events for the Tokyo Games offer a hint of what’s to come: During the US track and field trials last week, hammer thrower Gwen Berry turned away from the podium while the national anthem played, and draped a t-shirt over her head that read “athlete activist.” Berry previously raised her fist on the podium during the 2019 Pan-American Games in Peru, and the US Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC) reprimanded her for violating Rule 50. (She told NBC Sports that she lost two-thirds of her income after that, because sponsors dropped her.)

The USOPC later apologized to Berry after it changed the rules regarding political protest, based on the recommendations of a council of US athletes. From now on, “the USOPC will not sanction Team USA athletes for respectfully demonstrating in support of racial and social justice for all human beings,” according to new guidance from Dec. 2020.

There’s also an important element of public pressure on the IOC, and commercial considerations when it comes to sponsors and their tolerance for controversy. “Is [IOC president] Thomas Bach really going to stand up to the John Carlos and Tommie Smith of their day? I don’t think it would make commercial sense,” says Simon Rofe, a reader in diplomatic studies at SOAS University of London, who works with national sports governing bodies in the UK. “I think we will see some athlete protest [at the Tokyo Olympics]. Being sensible and dealing with it in a managed fashion is probably the best course of action for the governing bodies. The truth of it will be shaped by [whether] sponsors think it’s a good idea.”

The controversy over Olympic host cities

It’s not just athlete activists who are challenging Olympic norms around political neutrality.

The choice of host cities for the Games has long been controversial—think back to the Nazi Olympics—but it has become even more so in recent years. The Games are prohibitively expensive for host cities. (Montreal spent 30 years paying off the debt it accrued hosting the 1976 Games.) They are breeding grounds for corruption (pdf). They have a negative environmental impact, and can carry a humanitarian cost. Every four years, “poor people who find themselves living in the wrong place, on land that the Games need for stadiums and parking lots…are, per Olympic tradition, evicted, and sent packing into a difficult new life,” according to sports writer Bill Donahue in the Washington Post.

That’s why hosting the Games is an increasingly unpopular project in democracies, where politicians are accountable to voters who don’t want to foot the bill and deal with construction, traffic, and controversy. In 2015, six cities submitted bids to host the 2022 Winter Olympics: Oslo, Stockholm, Lviv, Krakow, Beijing, and Almaty. Of those, four dropped out, leaving the IOC with a choice between two autocracies: Kazakhstan or China. It picked Beijing.

(One of the possible solutions to this problem is to host the Olympics in the same place every time; while the idea routinely comes up, it’s rarely ever taken seriously.)

Meanwhile, a large-scale boycott of the Beijing Winter Games is becoming more likely. Many Western countries have accused the Chinese government of human rights violations. Some have gone as far as to call what is happening in Xinjiang, in northwest China, a “genocide.” It’s a label the Chinese categorically reject; they say the restrictions are a response to the risk of domestic terrorism. Attending the Games could be seen as a tacit endorsement of the Chinese government’s governance model.

One of the politicians calling for a diplomatic boycott is David Lega, a Swedish member of the European Parliament and former Paralympic swimmer. He has spoken to sports federations and Olympic committees about creating new criteria for the host city bidding process for major sporting events that include considerations like human rights. He believes that adapting that process is “in the sporting movement’s own interest.”

It’s a question that more governments are increasingly looking at: The European Parliament’s Subcommittee on Human Rights recently organized a workshop on the inclusion of “human rights considerations in the preparation and organization of large sports events.” The European Parliament endorsed a motion calling for a diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Games, as did the UK’s House of Commons, while Canada’s House of Commons called on the IOC to move the games.

The Tokyo and the Beijing Games will be a test of the Olympic movement’s ability to balance ideals of political neutrality with geopolitical dynamics and athletes’ personal freedoms, says Boykoff. “The times are changing.”

Correction: This story was updated to clarify that David Lega supports a diplomatic boycott of the Tokyo Games.