Half of Mumbai’s registered voters didn’t go to the polls

Mumbaikars have plenty to complain about—and they do. Frequently. In the trains and in their drawing rooms, the residents of India’s commercial capital are always griping about their congested streets, overcrowded public transport, corrupt politicians and polluted air. Yet, when they had the opportunity to register their protest against their representatives in the Lok Sabha, just over half of them turned out to vote.

Mumbaikars have plenty to complain about—and they do. Frequently. In the trains and in their drawing rooms, the residents of India’s commercial capital are always griping about their congested streets, overcrowded public transport, corrupt politicians and polluted air. Yet, when they had the opportunity to register their protest against their representatives in the Lok Sabha, just over half of them turned out to vote.

By the end of April 24, only 52.6% of Mumbai turned up to vote in the sixth phase of the general election.

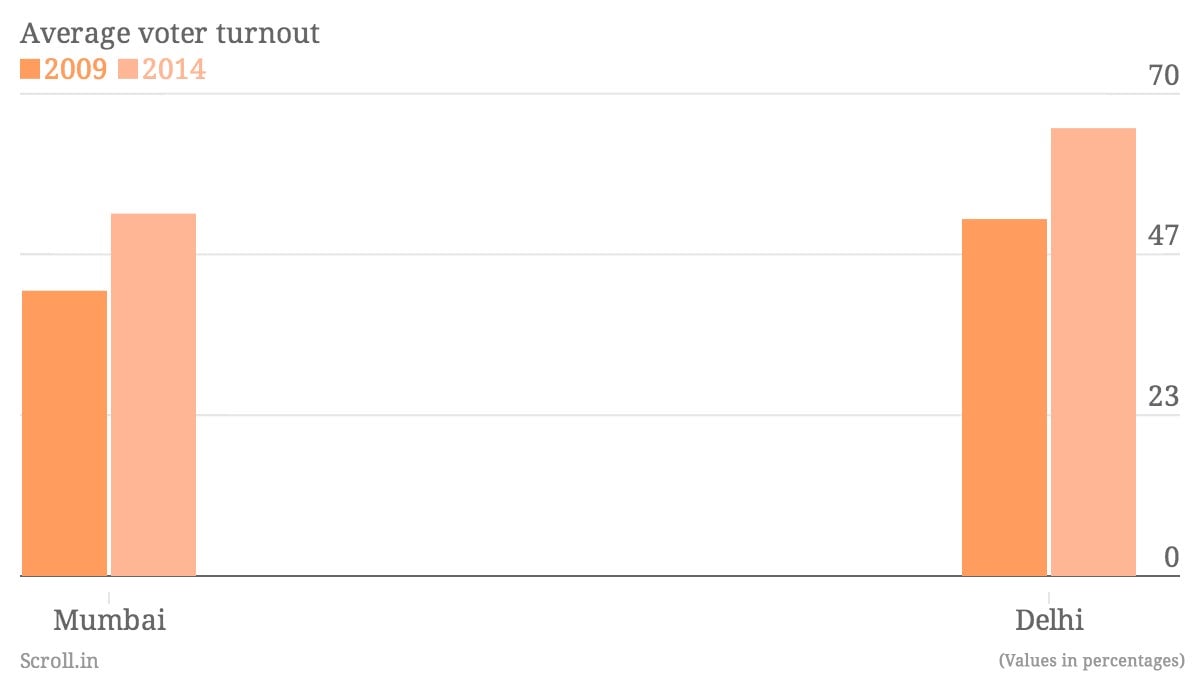

To be fair, this is a significant 11 percentage point leap from the 2009 Lok Sabha election, which saw a voter turnout in Mumbai of only 41.4%. In itself, however, 52.6% is still an unremarkable statistic: Maharashtra’s overall voter turnout nearly hit 60% this year and Delhi notched up 65%.

By 3pm, Mumbai South recorded a turnout of just 29% but three hours later, by the time polling closed, it managed to hit 54%. The highest turnout in the city was in South Central, where 55% of voters came out to exercise their franchise.

One reason for the spotty record, observers say, was that many potential voters found themselves missing from the rolls. Reports suggested that the names of 15% of eligible voters in Mumbai had had been deleted from the records, while as many as six million voters across Maharashtra found themselves missing from the election list.

“There are many people who wanted to vote today but could not, because of the deletions,” said Shyama Kulkarni, a trustee at non-profit organisation AGNI. The percentage of voter turnout is typically calculated against the total number of registered voters (around 31.7 million in Mumbai). “But if many registered voters don’t show up on the final list, the statistics for voter turnouts will not be accurate,” said Kulkarni.

The problem was evident at several polling stations on Thursday, where voters got into heated arguments with officials about the absence of their names on the lists. “There are 12 of us in my building who are mysteriously missing from the list – some of them got their voter ID cards from the Election Commission just a few months ago, and one of them has been voting for 30 years,” said a resident of Bandra’s Pali Hill who did not wish to be named. “There are five other buildings in my area where large numbers of residents are facing the same problem.”

Election Commission officials claim that names have been deleted only if voters have moved out of their homes, after repeated house checks. Kulkarni believes many Mumbai-ites have not been active enough to look for their names on the lists well in advance. “But if the Election Commission conducted these checks in October or November, it is their duty to publicise it widely,” she said.

In addition, thousands of people who had registered to vote months ago found that their names had not been included in the list. (Also read “My battle to participate in the world’s greatest show of democracy: a first-time voter’s struggle to be included on the rolls.)

None of this, however, provides a satisfactory explanation for why Mumbai’s voter turnout has been among the lowest in the country and continues to be well below the national average of 59.7% recorded in the last elections.

S Parasuraman, director of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, believes that the voter apathy has largely to do with the socio-economic disparities in a city in which approximately half the population lives in slums. Mumbai’s rich, he said, don’t feel the need to come out to vote because they believe they can purchase the services they need and don’t need government officials to help them to do that.

The last decade has seen the rise of the city’s first gated communities, which offer residents wide roads, clean parks and interrupted water supply—facilities that many other Mumbaikars are denied. “In fact, in many gated housing societies in Mumbai, I’ve heard that the security guards don’t even allow election officers to enter the building for verification of voters’ names,” said Parasuraman.

This post originally appeared on Scroll.