The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced Tuesday that it would reinstate a federal moratorium on evictions in parts of the US experiencing high levels of Covid-19 transmission. The agency came under mounting pressure from Congressional Democrats as the pandemic’s new delta variant has spread across the country.

The new temporary measure, which is set to expire on Oct. 3, is a swift reversal of the CDC’s position just days earlier, when it insisted that the eviction protections expiring on July 31 would be the last. The new protections apply to areas where community spread of Covid-19 is deemed “substantial” or “high,” but in effect, this currently covers more than 80% of counties in the country.

The CDC’s original eviction moratorium, put in place as an emergency public health measure back in September of 2020, expired on Saturday July 31, after four extensions. By the following Monday, eviction filings started to increase in courts around the country. After previously saying its hands were tied, the Biden administration reinstated the ban on evictions Tuesday, though it is likely to face legal challenges in the courts. At the very least, administration officials are hoping it will be enough time for lagging rent relief efforts to pick up and reach more people. By the end of June, only about 6.5% of $47 in emergency relief funds had been distributed.

Who is protected by the eviction ban?

Not all renters in a covered area are automatically given blanket protection under the moratorium. Tenants seeking protection must present landlords with a signed declaration stating that in addition to living in an area with Covid risk, their situation meets the following criteria:

- They have attempted to obtain government assistance for rent relief

- They either: have an income no higher than $99,000 per year ($198,000 for couples filing jointly), were not required to file a 2020 tax return, or received a pandemic stimulus check

- They are unable to pay rent because of loss of income, work, or medical expenses

- They are making their best effort to pay at least part of their rent

- They have no other viable housing options; that eviction would lead to homelessness or an unsafe crowding situation

Are people still being evicted?

Even when previous federal protections were in place, millions of Americans lived on the brink of eviction. A recent US Census Bureau survey found that 3.6 million people are less than two months away from eviction, representing nearly half of US renters who are behind on payments. This group is disproportionately Black and Latinx, low-income, and city-dwelling.

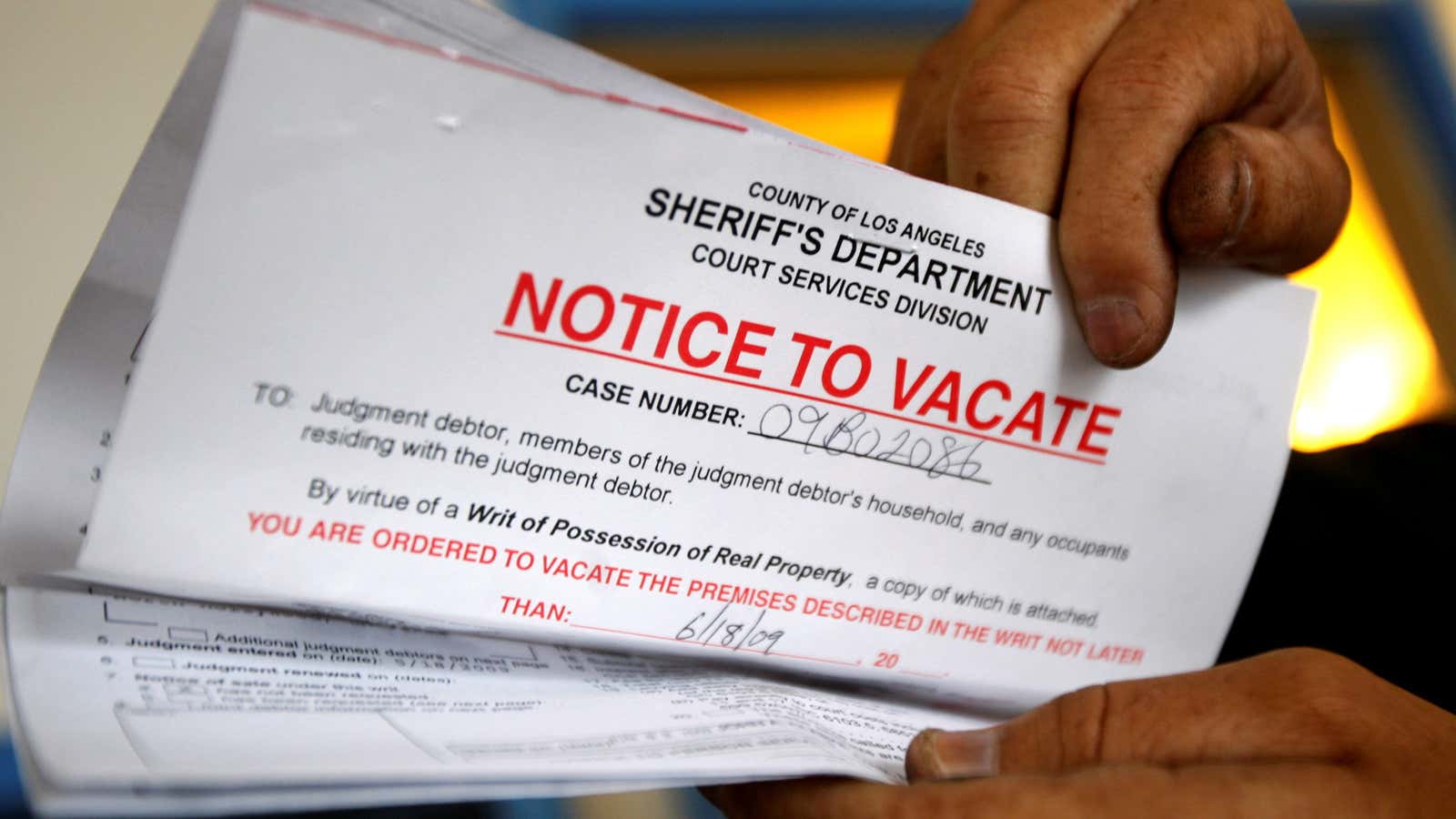

To be clear, moratoriums haven’t ended all evictions in the US. Tenants have still been evicted, legally and illegally, for other reasons, such as violating a lease or posing a safety risk to a building. Even in the three-day lapse between protections at end of July and August, sheriffs around the country began knocking on doors and issuing eviction notices. Still, local and national moratoriums have been credited with preventing more than 1 million evictions during the pandemic.

Why did the old moratorium expire?

The first limited federal protection for renters was passed with the CARES Act in March 2020, but the CDC issued a more expansive moratorium in September. At the time, a group called the Covid-19 Eviction Defense Project estimated that one in five American renters was at risk of eviction. Researchers at UCLA would later suggest that the expiration of 27 state eviction moratoriums over the summer of 2020 led to 433,700 Covid-19 cases and 10,700 deaths.

The federal moratorium was set to expire at the end of last year, but has since been extended four times; the CDC said its most recent extension would be the last. That might be because the ban’s legal standing is now in question. Earlier in July, a federal appeals court said the CDC lacked the authority to issue the moratorium.

How is the eviction ban affecting landlords?

Landlords have fought the federal eviction moratorium from the start: In September 2020, the National Apartment Association, a group that represents owners, sued the CDC for overreach. Just this week, the group filed another lawsuit for damages on behalf of landlords. It claims that as of the second quarter of 2021, tenants owe $57 billion in unpaid rent, and landlords are now responsible for close to $27 billion in debt not covered by federal rental assistance.

The hardest-hit groups are mom-and-pop landlords, those who own fewer than 10 properties and rely on rent payments as a primary source of income. As costly as rent delinquency is, evicting a tenant is also expensive: An Urban Institute analysis found that evictions at the end of the moratorium period would cost landlords between $2.6 billion and $4.6 billion in processing and fees.

California & New York are extending protections

Even before the CDC’s ban, state and local authorities had started passing their own eviction moratoriums, which made a significant difference in lowering evictions around the country. Currently, 10 states have extended their eviction protections past the federal deadline in some capacity: California, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, New Jersey, New Mexico, and Washington, plus the District of Columbia.

California and Washington have some of the longest timelines, with evictions and utility shut-off moratoriums in place through Sept. 30. Other protections evaporate in August and some states, including Minnesota, established “off ramp” timelines based on eligibility for pandemic-related rental assistance.

What about rent relief?

Congress has allocated nearly $47 billion in rental assistance since December, but getting that money into the hands of people who need it is turning into a race against time. The Treasury Department reported that just 6.5% of these funds—about $3 billion—had been distributed by June.

Much of the delay boils down to bureaucracy: The funds are being allocated through a web of state and local programs moving at different speeds and with varying degrees of centralization. Another key issue is awareness. Tenants need to apply for rental assistance, but recent survey data indicates that 40% of landlords and 50% of renters don’t know relief dollars are available.

The pressure is on now for state and local governments to get relief programs up and running, and to get the word out to renters who need it most. The Treasury warned that jurisdictions that haven’t spent 65% of their allocated funds by Sept. 30 will see the money reallocated.

“Initially, we were particularly concerned about an eviction cliff,” David Dworkin, president and CEO of the National Housing Conference told The Hill in late June. “What we’re watching now is a slow-motion car crash, and we really need to engage very deliberately in avoiding it.”