A wave of companies and governments are announcing new vaccine policies, requiring people to get inoculated against Covid-19 in order to keep their jobs, go to the office, dine in restaurants, or attend indoor performances.

Such policies seem to be effective in persuading at least some unvaccinated people to get their shots. They’re also bound to be controversial. One of the most common arguments raised by dissenters is that vaccine mandates infringe upon unvaccinated people’s human rights and civil liberties.

But do these arguments hold up?

Quartz spoke with a bioethicist, a scholar in healthcare law, and a policy counsel at the New York branch of the American Civil Liberties Union to find out, and to ask what concerns business leaders and policy makers should weigh as they consider implementing vaccine requirements.

What are human rights and civil liberties?

Let’s clear this up at the outset, as human rights and civil liberties are terms that are often used fairly interchangeably.

Human rights are those rights that all people hold simply by virtue of existing, whoever they are and wherever they live. The UN’s groundbreaking 1948 document, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, outlines these rights, including the idea that all people have the right to freedom of opinion and expression, and the right to freedom of religion.

Civil liberties, meanwhile, refer to the rights accorded to people under a country’s constitution or bill of rights, or other forms of legislation.

“There’s a lot of overlap,” says law professor Mark Hall, director of the Health Law and Policy program at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. “In brief, civil liberties focus mainly on freedoms to do what you want to do. Human rights also include rights to be protected from harm.”

People who worry about vaccine requirements getting in the way of their rights may be referring to both kinds of concerns—the freedom to refuse vaccination for personal, ideological, or religious reasons, and (in the cases of those who worry about the safety of the vaccine and its side effects, despite overwhelming evidence that vaccines are safe) the right to be protected from harm.

Liberty and public health

A crucial point in the vaccine debate is that human rights give all people the right to be protected from harm. Covid-19 poses a major public health risk—not just to people who are unvaccinated by choice, but to those who cannot yet get vaccinated, such as children under age 12, and people in lower-income countries that still lack a sufficient supply of vaccines, or to people who did get vaccinated but develop breakthrough infections. (While vaccinated people are protected against serious illness in breakthrough cases, they can pass the virus on to others.)

“In ethics, there’s this idea that you can do things as long as you don’t harm other people,” says bioethics professor Matthew Liao, director of the Center for Bioethics at New York University. “[W]hen you don’t get vaccinated, you’re putting people in danger.”

Hall notes that in the 1905 case Jacobson v. Massachusetts, the US Supreme Court upheld the states’ authority to mandate vaccinations (in this case, for smallpox) for this very reason. The court noted in its opinion:

“The liberty secured by the Constitution of the United States does not import an absolute right in each person to be at all times, and in all circumstances, wholly freed from restraint, nor is it an element in such liberty that one person, or a minority of persons residing in any community and enjoying the benefits of its local government, should have power to dominate the majority when supported in their action by the authority of the State.”

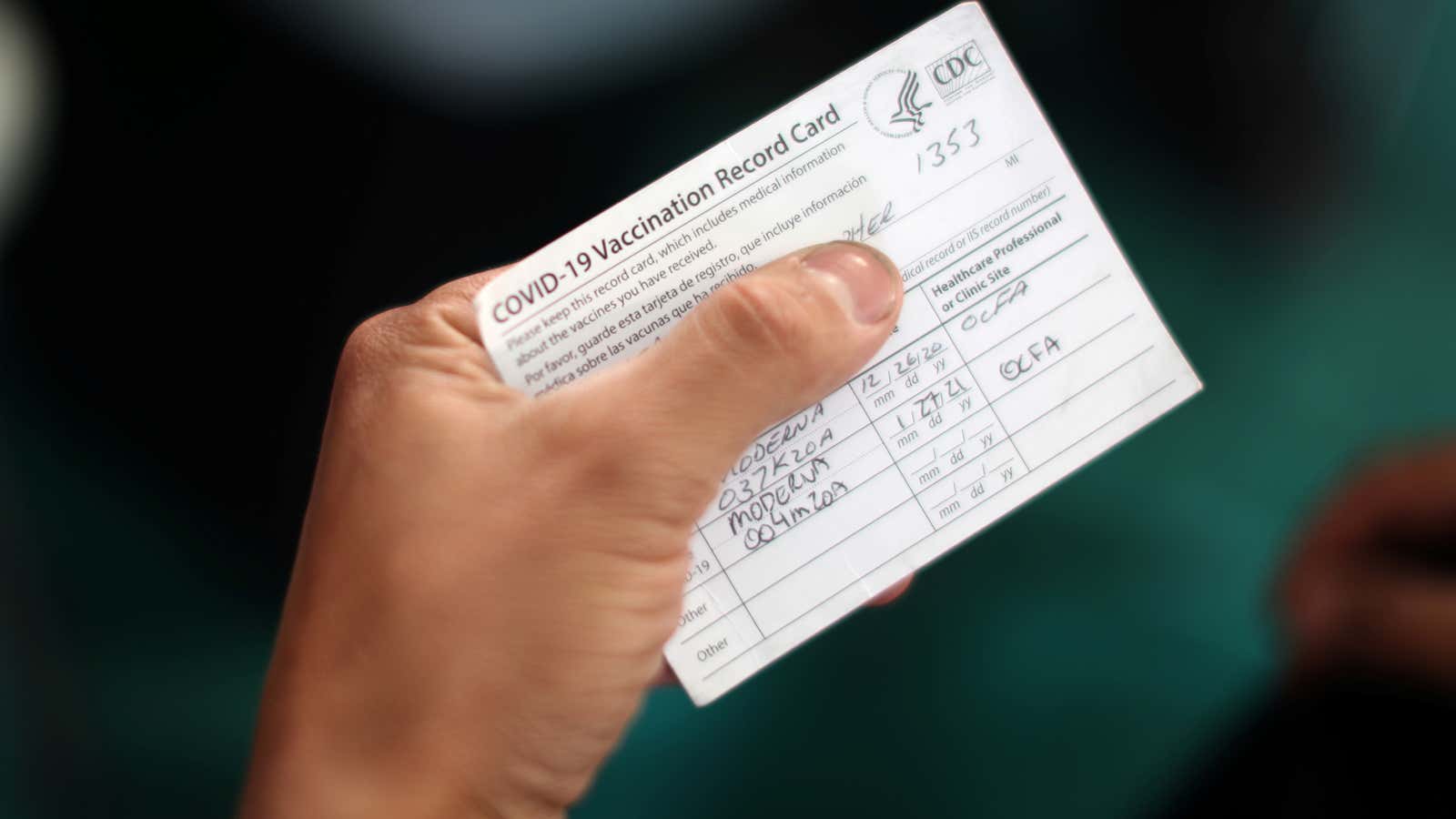

As Liao points out, the US and many other countries already have vaccine requirements in place to protect against other diseases (like polio and the measles). “If you go to schools you need to show immunization records. If you come to the US, you need to show you’ve gotten certain shots,” he says. “I’m not concerned about it as a restriction of liberty.”

Is there a fundamental right to refuse vaccination?

Both Liao and Hall draw comparisons between vaccine requirements and speed limits. A person might want to drive 100 miles per hour down a residential street, they might not believe in speed limits, but they are still required to abide by them for the sake of people who might be crossing the street or backing out of their driveways.

“Because one person’s choice affects the health of other people and the public at large, people do not have a fundamental right to refuse vaccination,” Hall concludes.

People also don’t have an inherent right to frequent stores, restaurants, and venues regardless of their behavior. Think of the vast number of businesses that hang signs saying “No shirts, no shoes, no service,” or rules that bar people from smoking cigarettes indoors or carrying weapons inside.

Private business owners have their own rights when it comes to shaping their environments. “They want to be able to tell everyone, ‘When you come here, you’re safe,’” says Liao. “They have a right to protect their business interests.” Workers, meanwhile, have the right to feel safe at their jobs.

Do vaccine passes discriminate against the unvaccinated?

In the US, federal laws prevent businesses from refusing service or denying employment to people on the basis of traits like race, sex, and disability. The unvaccinated are not a protected category.

There is, however, an important caveat: Vaccine mandates and passes could violate the rights of people who object to vaccines for religious reasons, or who can’t get vaccinations for medical reasons (like allergies). Liao says that exemptions and accommodations should be provided to people who fall into these groups.

What about vaccine equity?

Despite their support for requiring shots, all of the experts we consulted also voiced concerns about how vaccine policies could potentially restrict opportunities for people who are already marginalized, given that vaccination rates in the US and elsewhere tend to be lower among low-income populations as well as Black and Hispanic populations.

Allie Bohm, policy counsel at the New York Civil Liberties Union, says that in New York City, “vaccine distribution is not where it should be.” She notes that the poorest district in the borough of Brooklyn, (district 16, which includes the neighborhoods of Brownsville and Ocean Hill), has no vaccination sites. The city’s vaccine rollout has largely depended on traditional pharmacy networks and mass-vaccination sites, she says, bypassing the community-based organizations and senior centers where “Black, brown, and low-income New Yorkers are most likely to go and get care.”

And there are other wrinkles to consider. Low-income workers may be struggling to find time to get a vaccine and nurse the potential side effects while juggling work and childcare. Or they may worry that they can’t afford the vaccine despite its being free. Undocumented people may be unclear about whether getting the vaccine could jeapordize their immigration status (in the US, undocumented people are eligible for vaccines and are not required to provide Social Security numbers or state-issued IDs, but healthcare providers may ask for documentation nonetheless, adding to the confusion).

“We’ve got all these barriers to vaccination that we haven’t solved, and that have real racial and socioeconomic justice implications,” Bohm says. “So I think a lot about, when we are going to make vaccine passports the gatekeeper to everywhere, who are we cutting off from society and what have we done to make sure the people who want to get vaccinated are able to get vaccinated, so they can continue to participate?”

A number of steps can be taken to ensure that vaccine requirements don’t have an unjust impact on marginalized communities. In addition to expanding vaccine access, Hall suggests accepting “immunity passports,” designating people who have recovered from Covid-19, in lieu of proof of vaccination. “Including immunity acquired by infection helps to achieve equity because disadvantaged groups have suffered more from Covid infections,” he says.

Vaccine requirements and privacy issues

Another potential area of concern when it comes to vaccine rollouts relates to privacy. People have a right to privacy, Liao says. If vaccine mandates allowed governments or businesses to digitally collect and store extraneous information, that would be an issue.

“If it’s just a pass that shows you’ve been vaccinated, I don’t think that’s much of a problem,” Liao says. “If it’s a pass where they start to track you everywhere you go”—say, keeping track of where you’ve used the pass at various restaurants and venues, and who you’ve been with—”we might start to worry about that type of surveillance.”

Bohm points out that while the European Union has comprehensive digital privacy laws under the General Data Protection Regulation, the US doesn’t have comparable protections in place. “It’s a particular risk for people who whether for fear of deportation, criminalization, or any other reason, may be afraid to share personal information with the government or with private companies,” she says. “I think it’s really important to put in place legal protections to make sure we’re not creating a permanent surveillance system that’s scooping our health information and tracking our every move, because that’s going to cut the most vulnerable off from society.”

To that point, both Liao and Bohm say, it’s also important that vaccine requirements permit people to present either physical records of vaccination or digital passes. Not only will this alleviate concerns about digital tracking and surveillance, it will also ensure that people without smartphones—including the third of US adults age 65 and older who say that they own cell phones but not smartphones—aren’t prevented from participating in various aspects of public life.

Protecting people’s rights with vaccine pass rollouts

The consensus among the three experts is that vaccine mandates and requirements do not inherently infringe upon people’s rights, particularly given the very real public health crisis that Covid-19 presents. But it’s important to stay vigilant about how these policies are designed and applied. For example, as Bohm notes, if a business checks Black people’s vaccine passes but not white people’s—a real possibility, given the discrimination that Black people often face in retail stores—there’s a clear problem.

“I think the bottom line is really how are these things being implemented, and what are we doing to make sure that we have vaccine access and that we’re protecting people’s personal information,” Bohm says.

Also important, particularly as the world grapples with the rise of even more contagious Covid-19 variants, is remaining flexible about changing vaccine requirements and policies as circumstances change and new information comes to light. As Hall and co-author David Studdert wrote in a March article for the New England Journal of Medicine: “The past year has taught us that pandemic policies that are sensible one month may need to be rethought a month later [… but] current circumstances demand immediate policies that offer reasonable leeway for balancing protection of public health with a return to pre-pandemic life.”