We read the 4000-page IPCC climate report so you don’t have to

The most important takeaways from the new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report are easily summarized: Global warming is happening, it’s caused by human greenhouse gas emissions, and the impacts are very bad (in some cases, catastrophic). Every fraction of a degree of warming we can prevent by curbing emissions substantially reduces this damage. It’s a message that hasn’t changed much since the first IPCC report in 1990.

The most important takeaways from the new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report are easily summarized: Global warming is happening, it’s caused by human greenhouse gas emissions, and the impacts are very bad (in some cases, catastrophic). Every fraction of a degree of warming we can prevent by curbing emissions substantially reduces this damage. It’s a message that hasn’t changed much since the first IPCC report in 1990.

But to reach these conclusions (and ratchet up confidence in their findings), hundreds of scientists from universities around the globe spent years combing through the peer-reviewed literature—at least 14,000 papers—on everything from cyclones to droughts.

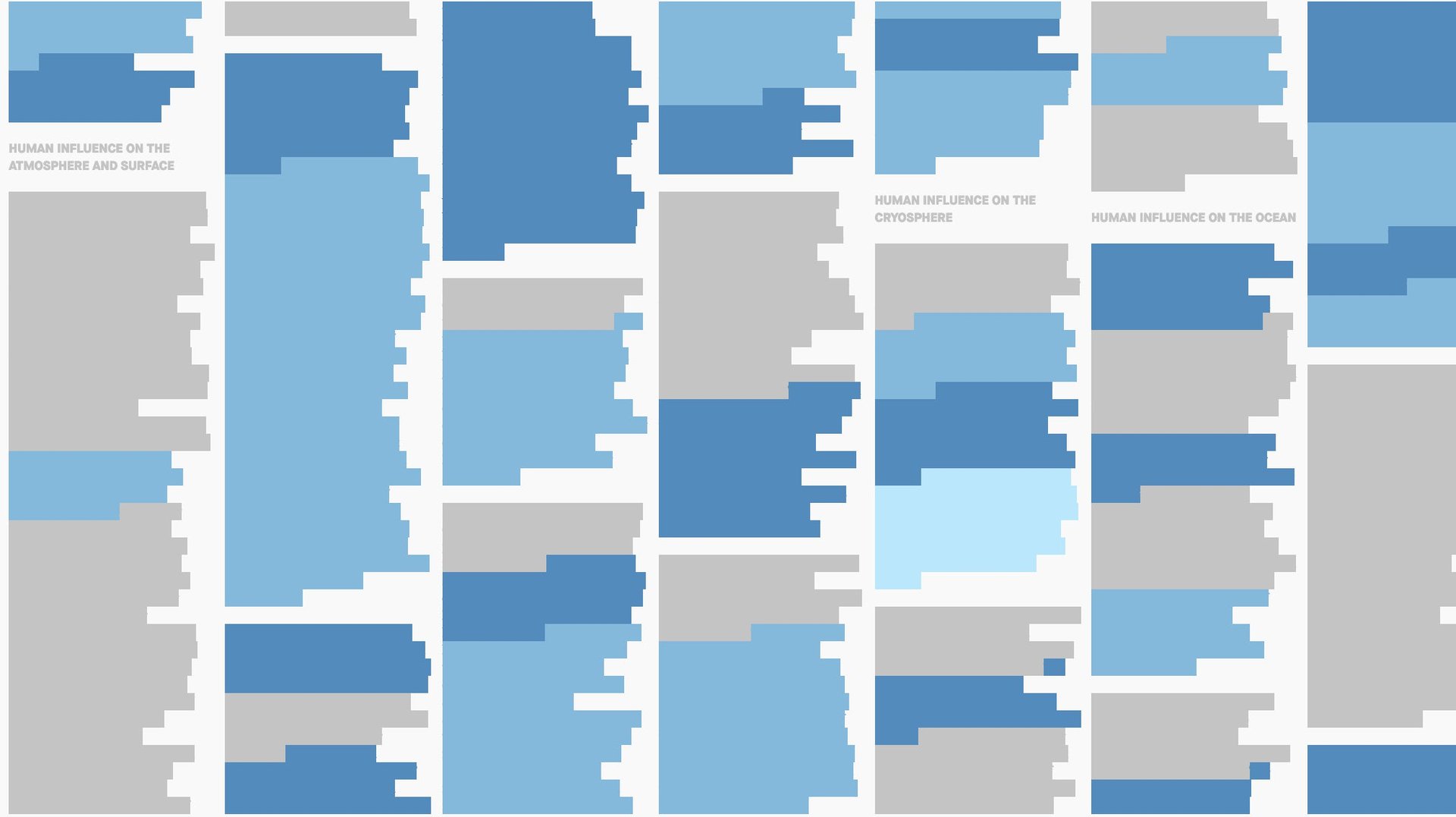

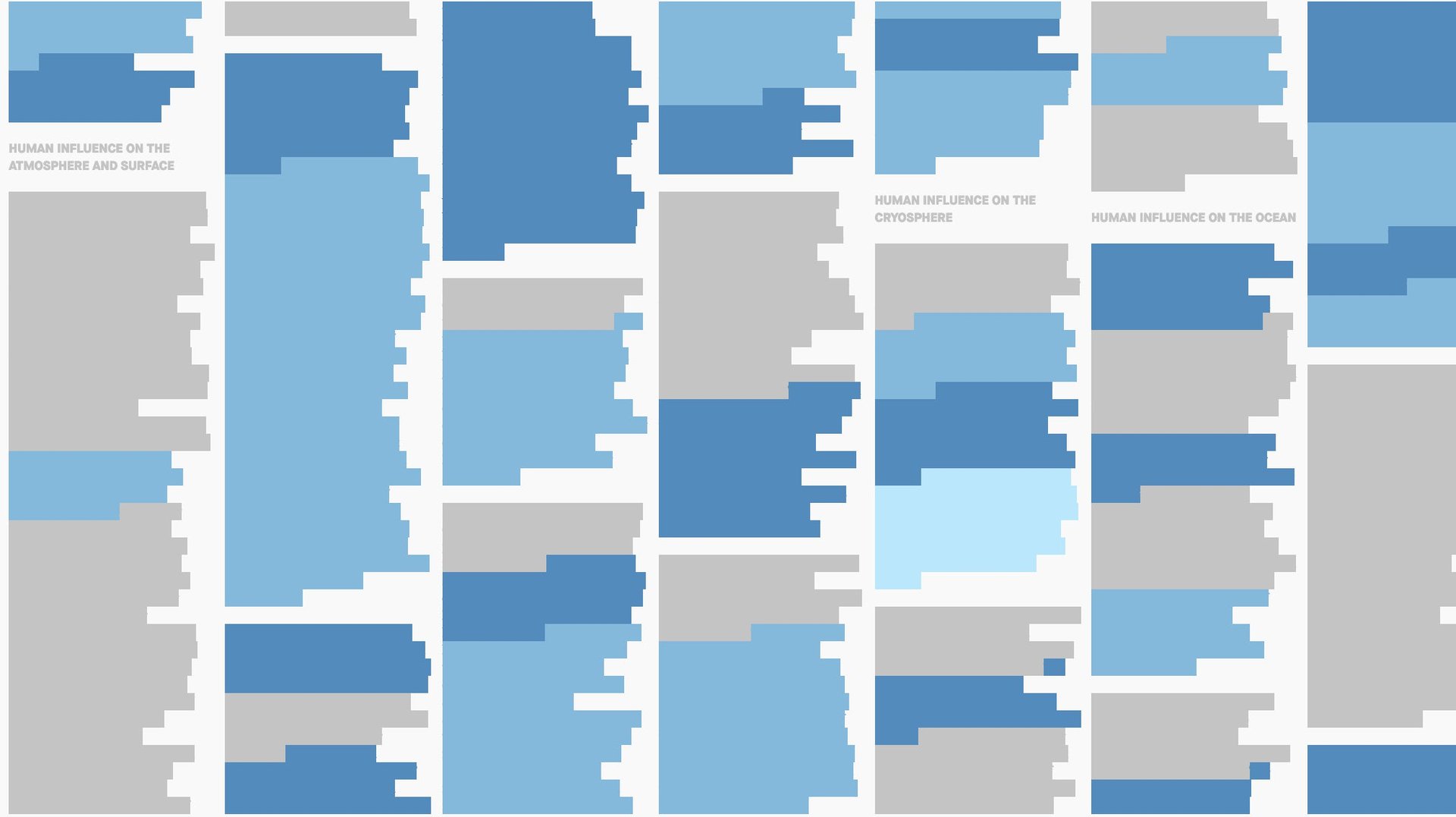

The final Aug. 9 report is nearly 4,000 pages long. While much of it is written in inscrutable scientific jargon, if you want to understand the scientific case for man-made global warming, look no further. We’ve reviewed the data, summarized the main points, and created an interactive graphic showing a “heat map” of scientists’ confidence in their conclusions. The terms describing statistical confidence range from very high confidence (a 9 out of 10 chance) to very low confidence (a 1 in 10 chance). Just hover over the graphic and click to see what they’ve written.

Here’s your guide to the IPCC’s latest assessment.

CH 1: Framing, context, methods

The first chapter comes out swinging with a bold political charge: It concludes with “high confidence” that the plans countries so far have put forward to reduce emissions are “insufficient” to keep warming well below 2°C, the goal enshrined in the 2015 Paris Agreement. While unsurprising on its own, it is surprising for a document that had to be signed off on by the same government representatives it condemns. It then lists advancements in climate science since the last IPCC report, as well as key evidence behind the conclusion that human-caused global warming is “unequivocal.”

CH 2: Changing state of the climate system

Chapter 2 looks backward in time to compare the current rate of climate changes to those that happened in the past. That comparison clearly reveals human fingerprints on the climate system. The last time global temperatures were comparable to today was 125,000 years ago, the concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide is higher than anytime in the last 2 million years, and greenhouse gas emissions are rising faster than anytime in the last 800,000 years.

CH 3: Human influence on the climate system

Chapter 3 leads with the IPCC’s strongest-ever statement on the human impact on the climate: “It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the global climate system since pre-industrial times” (the last IPCC report said human influence was “clear”). Specifically, the report blames humanity for nearly all of the 1.1°C increase in global temperatures observed since the Industrial Revolution (natural forces played a tiny role as well), and the loss of sea ice, rising temperatures, and acidity in the ocean.

CH 4: Future global climate: Scenario-based projections and near-term information

Chapter 4 holds two of the report’s most important conclusions: Climate change is happening faster than previously understood, and the likelihood that the global temperature increase can stay within the Paris Agreement goal of 1.5°C is extremely slim. The 2013 IPCC report projected that temperatures could exceed 1.5°C in the 2040s; here, that timeline has been advanced by a decade to the “early 2030s” in the median scenario. And even in the lowest-emission scenario, it is “more likely than not” to occur by 2040.

CH 5: Global carbon and other biochemical cycles and feedbacks

Chapter 5 quantifies the level by which atmospheric CO2 and methane concentrations have increased since 1750 (47% and 156% respectively) and addresses the ability of oceans and other natural systems to soak those emissions up. The more emissions increase, the less they can be offset by natural sinks—and in a high-emissions scenario, the loss of forests from wildfires becomes so severe that land-based ecosystems become a net source of emissions, rather than a sink (this is already happening to a degree in the Amazon).

CH 6: Short-lived climate forcers

Chapter 6 is all about methane, particulate matter, aerosols, hydrofluorocarbons, and other non-CO2 gases that don’t linger very long in the atmosphere (just a few hours, in some cases) but exert a tremendous influence on the climate while they do. In cases, that influence might be cooling, but their net impact has been to contribute to warming. Because they are short-lived, the future abundance and impact of these gases are highly variable in the different socioeconomic pathways considered in the report. These gases have a huge impact on the respiratory health of people around the world.

CH 7: The Earth’s energy budget, climate feedbacks, and climate sensitivity

Climate sensitivity is a measure of how much the Earth responds to changes in greenhouse gas concentrations. For every doubling of atmospheric CO2, temperatures go up by about 3°C, this chapter concludes. That’s about the same level scientists have estimated for several decades, but over time the range of uncertainty around that estimate has narrowed. The energy budget is a calculation of how much energy is flowing into the Earth system from the sun. Put together these metrics paint a picture of the human contribution to observed warming.

CH 8: Water cycle changes

This chapter catalogs what happens to water in a warming world. Although instances of drought are expected to become more common and more severe, wet parts of the world will get wetter as the warmer atmosphere is able to carry more water. Total net precipitation will increase, yet the thirstier atmosphere will make dry places drier. And within any one location, the difference in precipitation between the driest and wettest month will likely increase. But rainstorms are complex phenomenon and typically happen at a scale that is smaller than the resolution of most climate models, so specific local predictions about monsoon patterns remains an area of relatively high uncertainty.

CH 9: Ocean, cryosphere, and sea level change

Most of the heat trapped by greenhouse gases is ultimately absorbed by the oceans. Warmer water expands, contributing significantly to sea level rise, and the slow, deep circulation of ocean water is a key reason why global temperatures don’t turn on a dime in relation to atmospheric CO2. Marine animals are feeling this heat, as scientists have documented that the frequency of marine heatwaves has doubled since the 1980s. Meanwhile, glaciers, polar sea ice, the Greenland ice sheet, and global permafrost are all rapidly melting. Overall sea levels have risen about 20 centimeters since 1900, and the rate of sea level rise is increasing.

CH 10: Linking global to regional climate change

Since 1950, scientists have clearly detected how greenhouse gas emissions from human activity are changing regional temperatures. Climate models can predict regional climate impacts. Where data are limited, statistical methods help identify local impacts (especially in challenging terrain such as mountains). Cities, in particular, will warm faster as a result of urbanization. Global warming extremes in urban areas will be even more pronounced, especially during heatwaves. Although global models largely agree, it is more difficult to consistently predict regional climate impacts across models.

CH 11: Weather and climate extreme events in a changing climate

Better data collection and modeling means scientists are more confident than ever in understanding the role of rising greenhouse gas concentration in weather and climate extremes. We are virtually certain humans are behind observed temperature extremes.

Human activity is more making high temperatures and extreme weather more intense and frequent, particularly rain, droughts, and tropical cyclones. While even 1.5°C of warming will make extreme events more severe, the intensity of extreme events is expected to at least double with 2°C of global warming compared to today’s conditions, and quadruple with 3°C of warming. As global warming accelerates, historically unprecedented climatic events are likely to occur.

CH 12: Climate change information for regional impact and for risk assessment

Climate models are getting better, more precise, and more accurate at predicting regional impacts. We know a lot more than we did in 2014 (the release of AR5). Our climate is already different compared to the early or mid-20th century and we’re seeing big changes to mean temperatures, growing season, extreme heat, ocean acidification, and deoxygenation, and Arctic sea ice loss. Expect more changes by mid-century: more rain in the northern hemisphere, less rain in a few regions (the Mediterranean and South Africa), as well as sea-level rise along all coasts. Overall, there is high confidence that mean and extreme temperatures will rise over land and sea. Major widespread damages are expected, but also benefits are possible in some places.

What we did:

The visualization of confidence is only for the executive summary at the beginning of each chapter. If a sentence had a confidence associated with it, the confidence text was removed and a color applied instead. If a sentence did not have an associated confidence, that doesn’t mean scientists do not feel confident about the content; they may be using likelihood (or certainty) language in that instance instead. We chose to only visualize confidence, as it is used more often in the report. Highlights were drawn from the text of the report but edited and in some cases rephrased for clarity.