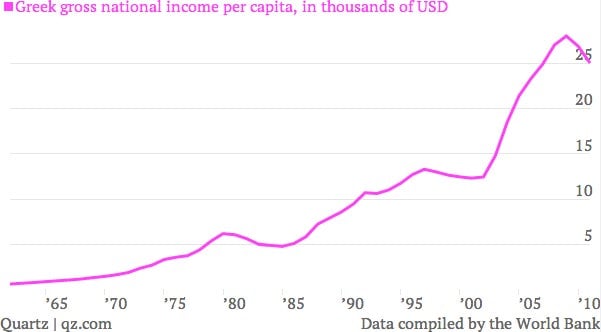

This chart shows why Greece still wants the euro even though it’ll hurt

As we noted earlier this week, Greece recently got an extension of two years to put in place the painful reforms that it needs to comply with the international bailout deals that are keeping the country afloat.

As we noted earlier this week, Greece recently got an extension of two years to put in place the painful reforms that it needs to comply with the international bailout deals that are keeping the country afloat.

Historically, when a country gets into the situation Greece finds itself in—with a massive overload of debt—it prints money to pay off its obligations. Such devaluation of a currency isn’t a perfect solution. Creditors are unhappy because they get paid back in currency worth a lot less than the money they originally lent. And consumers get hurt because they usually have to deal with a nasty bout of inflation that decreases their standard of living.

Nobody really likes the other option either. That option is known as “internal devaluation.” Essentially, it means the government cuts spending and raises taxes—that’s austerity. Austerity lowers economic growth and forces much of the country to stomach a steep pay cut. (In reality, inflation too amounts to a pay cut , because the cost of everything rises faster than people’s pay. But it’s not as hard to take because people still see the number on their paycheck rising even if it buys them less. Or at least that’s what economists think.)

That second path of internal devaluation is what Greece is trying to follow this time around. Why? Because the country ceded its right to print its own money by joining the euro zone.

And if the chart above is any indication, there’s a lot more Greek pay to be cut. You can see how sharply Greece’s national income per person shot up on the country’s adoption of the euro in 2001. Between 2001 and 2009, income per capita jumped 127% to more than $28,000, according to World Bank data.

The near immediate growth in national income after dropping the drachma and adopting the euro is a big reason why many Greeks remain eager to stay in the European monetary bloc. The paradox is, in order to stay, they’re likely going to have to watch a lot of those income gains slip away.