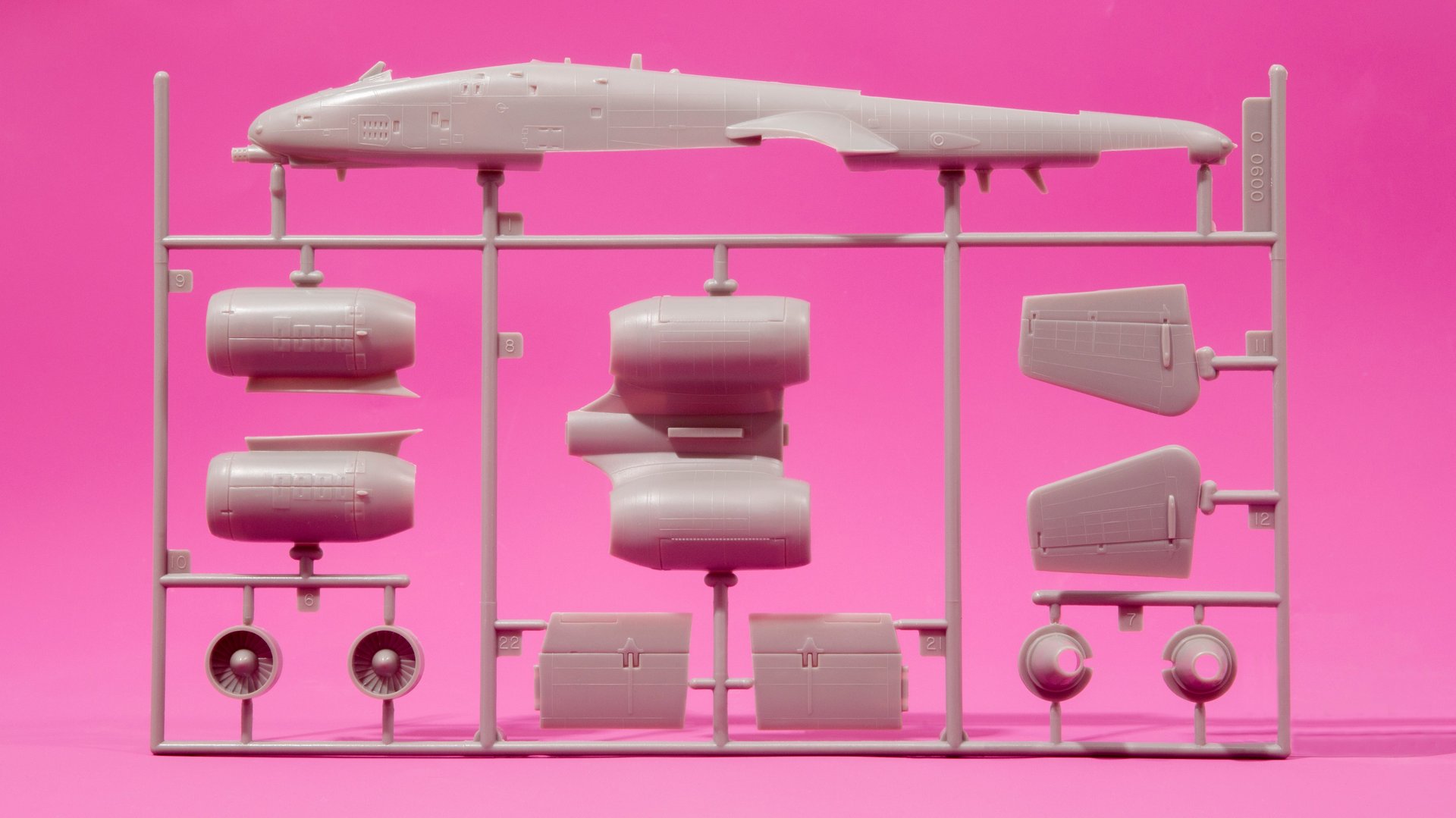

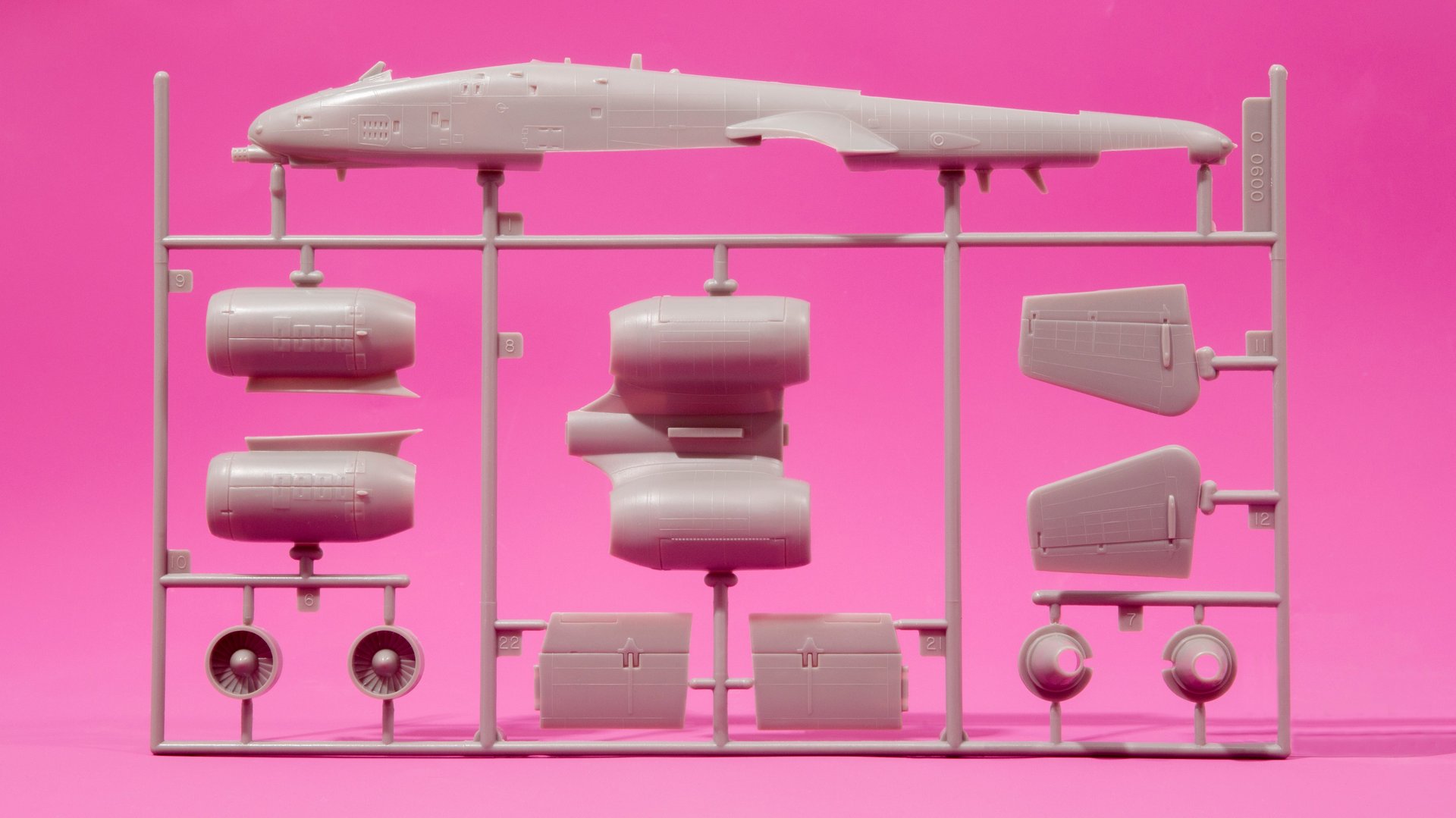

Six Sigma: Manufacturing perfection

In the early 2000s, GE was the world’s most powerful company, and its CEO Jack Welch was a firm believer in the Six Sigma system for eliminating errors in manufacturing. With GE as its poster child, management consultants spread the gospel of Six Sigma to companies everywhere. Now, as GE’s fortunes diminished, so has interest in Six Sigma. But what made this system so special in the first place, and how much is still useful today?

In the early 2000s, GE was the world’s most powerful company, and its CEO Jack Welch was a firm believer in the Six Sigma system for eliminating errors in manufacturing. With GE as its poster child, management consultants spread the gospel of Six Sigma to companies everywhere. Now, as GE’s fortunes diminished, so has interest in Six Sigma. But what made this system so special in the first place, and how much is still useful today?

Sponsored by American Express

Listen on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher

Featuring

Kira Bindrim is the host of the Quartz Obsession podcast. She is an executive editor who works on global newsroom coverage and email products. She is obsessed with reality TV.

Oliver Staley is the business and culture editor at Quartz, working with reporters covering the entertainment, fashion, travel, and lifestyle industries. He used to report on management, business, and economics. He’s obsessed with climbing the highest mountain in each state and owning every issue of the Fantastic Four comic book.

Jack Welch’s 2003 autobiography, Jack: Straight from the Gut

This episode uses the following sounds from freesound.org:

Karate Class.wav by Digital Gold Pictures

synth-and-flutes by Frankum

choir HALLELUJAH.wav by klankbeeld

Transcript

Kira Bindrim: If someone told you they got a black belt, you’d probably think they were talking about karate. But for people who follow the weird world of management theory, there’s actually another colored belt system, a way nerdier one, it’s called six sigma. Now, you might recognize Six Sigma if you’re a fan of 30 Rock. On the show, it’s constantly the butt of jokes. Jack Donaghy, the media executive played by Alec Baldwin, is a passionate fan of Six Sigma principles. He describes them not entirely accurately as teamwork, insights, brutality, male enhancement, hand-shakefulness, and play hard. But Six Sigma isn’t just a punch line. It’s a real set of techniques to help a company achieve manufacturing perfection. And that Jack Donaghy character, he learned Six Sigma at General Electric, which really did adopt it in the 1990s. GE CEO Jack Welch was obsessed with Six Sigma. He based promotions, bonuses, and stock options on the belt system. Six Sigma basically became GE’s religion. And because GE was the most valuable company in the world, Six Sigma got crazy popular. But when GE started a long, slow decline, so did Six Sigma. These days, you won’t see nearly as many black belts on LinkedIn profiles. And that fading popularity says something about business today. In a world that celebrates innovation is there room for a system that’s laser focused on perfection?

This is the Quartz Obsession, a podcast that explores the fascinating backstories behind everyday ideas, and what they tell us about the global economy. I’m your host Kira Bindrim. Today, Six Sigma, and what happens when a management theory loses its edge. I’m joined now by Oliver Staley, who is the business and culture editor at Quartz. He is based here in New York.

Is Six Sigma still relevant?

Kira Bindrim: So Six Sigma is a pretty wonky topic to get into. And I would say like at Quartz, we do not have a highly structured management system as it were. So I know that you didn’t get into this because you needed it for your work at Quartz as a manager. How did you get into this topic of Six Sigma?

Oliver Staley: As much as I’m obsessed with defect reduction in my editing, I have not applied a Six Sigma process to my to my stories. But I first encountered Six Sigma, I think like everyone else did, just in the popular press in like the in the 90s. General Electric was the most sort of celebrated company, and, you know, Jack Welch, who was sort of the Jeff Bezos of the time. I don’t recall any specific article, but I am fairly sure Six Sigma crossed my radar when Jack Welch was on the cover of Business Week, like every six months. I specifically recall a moment when I thought Six Sigma had entered into a different phase when my girlfriend at the time, who was in business school, asked me to proof her resume. She had inserted Six Sigma into her resume at various points to attract or signal her sort of fluency and management culture. So when I was thinking about story ideas, I remembered how sort of prevalent Six Sigma was in the culture and how it basically had vanished. And I wondered, why?

Kira Bindrim: What is it? What are we talking about?

Oliver Staley: So Six Sigma literally refers to deviations on a bell curve. If you can picture a bell curve, it’s all the way to the side, you know, where it’s basically a straight line. In terms of manufacturing, it refers to a near perfect process that’s 99.999% accurate. Three defects per million, something like that. Prior to the introduction of Six Sigma as a concept, companies were sort of operating at a three or four sigma level of defect reduction, which would make them something like 95% defect-free.

Kira Bindrim: And a sigma is one deviation?

Oliver Staley: Yeah. But don’t ask me more, because that’s all I know. That term is sort of indicative of the whole thing about Six Sigma, which is that it is taking some fairly sophisticated statistical concepts and allowing laymen to use them as if they know what they’re talking about. Evidence would suggest that not everyone who uses that term appreciates statistical significance and has an understanding of it.

Kira Bindrim: So if you asked 100 Six Sigma practitioners to really break down what Six Sigma means, they might not all nail it?

Oliver Staley: I wouldn’t say 100 would, no.

Six Sigma belts

Kira Bindrim: Let’s talk a little bit about where the Six Sigma system actually came from. Like, what is the origin story of this management theory?

Oliver Staley: So I think the important thing to remember here is that this came out of a manufacturing process. So the origin begins in Japan, after World War II. Because of the war, Japan’s industrial base had pretty much been wiped out, and so they were sort of rebuilding. They were very eager for ways to catch up in a hurry. So an American statistician named W. Edwards Deming ended up in Japan, and he was an evangelist of statistical analysis to eliminate defects in production. His systems were adopted and widely embraced, and the companies that adopted them did really well. So Japan quickly became an industrial powerhouse and by the 60s, and certainly the 70s, Japanese products were rapidly becoming the gold standard. You know, that was sort of the rise of Honda and Toyota and American car manufacturers like General Motors and Ford were building these massive, clunky, inefficient cars. And so there was a lot of attention being paid on how did Japan do this? During this period, you know, American companies were very eager to adopt Japanese systems. And one of the catalysts was a NBC documentary titled something like “if Japan can do it, so can we.”

Sample: In a recent American study of one type of integrated circuit, the best American product failed six times more often than the best Japanese product. Now, with our productivity in decline, more American companies are sending officials to Japan to see for themselves.

Kira Bindrim: So an American statistician goes to Japan, develops these principles, they really catch on in Japan because Japan is post-war, highly focused on reviving manufacturing. And now we have Six Sigma. Who names it Six Sigma?

Oliver Staley: It was a guy at Motorola, I believe his name is Bill Smith.

Kira Bindrim: So if I am a practitioner of Six Sigma, if I am a true believer, what does that mean? How does that manifest day-to-day?

Oliver Staley: Well, this is this gets into sort of both the appeal and the flaws of Six Sigma as a broader management concept. If you are involved in manufacturing and you’re trying to build a better airplane engine, you would be using Six Sigma to make sure that every time a jet engine comes off the assembly line it doesn’t have flaws. It gets a lot fuzzier when you’re involved in management, or human resources, or sales when you are trying to apply this process to your day-to-day function as a salesperson. And frankly, this is how Six Sigma sort of collapsed—it was extended into processes that had no use for it.

Kira Bindrim: Where do the belts come in? You know, I want to know about these belts.

Oliver Staley: The belts were basically borrowed from, as you mentioned, karate, or kung fu. Initially, there were just two, but then they’ve added, you know, every color of belt you can imagine has been added. These courses will sell you…

Kira Bindrim: Chartreuse? You talked about Motorola being one of the first companies that have coined the phrase, how did we go from Motorola to the widespread popularity that we’re saying happened in the US?

General Electric and Six Sigma: A case study

Oliver Staley: So a lot of it has to do with General Electric. Jack Welch was always looking for an edge. And Welch had already been hearing from his managers that quality control was becoming an issue at General Electric. I think the company was growing really fast at that point and they were doing a lot of different things. He was told that the company could save billions of dollars by weeding out defects and improving quality control. So at that point, he was all in, and Six Sigma became like the corporate religion at General Electric.

Kira Bindrim: What does that corporate religion aspect look like in the day-to-day, how did they implement it?

Oliver Staley: So they basically required every manager to undergo Six Sigma training, so thousands of managers, they spent, I think, something like a billion dollars over the first couple of years in training all these managers. Then they tied it to managers bonuses, like so stock options were reserved for managers who I think had gotten a black belt in Six Sigma. There’s a very telling anecdote in Welch’s autobiography: They were going to promote some guy to like be head of their nuclear unit. And he was good but they were not convinced of his devotion to Six Sigma principles. So he had to fly from California to Hartford, Connecticut, and essentially convince the muckety mucks at General Electric that he was sufficiently committed. It’s easy to draw parallels between Six Sigma and religion, but there is a certain like, you know, you need to be committed to this to this practice and its rituals and its faith in order to advance at General Electric.

Kira Bindrim: Okay, tell me a little bit about Jack Welch. He strikes me as a bit of a character.

Oliver Staley: He was sort of this like pugnacious, Boston, Irish guy who embraced a kind of ruthlessness but with a very sort of cheerful quality. And you know, he loved the media and the media loved him.

Kira Bindrim: Did he understand the statistical background to Six Sigma?

Oliver Staley: No, he admits he did not in his autobiography, but he knew enough to hire the people who did.

Kira Bindrim: Are there other companies that we know were at one point really invested in Six Sigma?

Oliver Staley: It became every company. Like, it was not just companies, but nonprofits, and government. It became like pixie dust that everyone wanted to sprinkle on their business and consultants began just selling it. It’s easy to make fun of, but you want to be on a plane that’s going through a Six Sigma process. You don’t want planes with a lot of defects, you don’t want your products to fall apart. And you know, what’s happened is like, we’ve just sort of assumed these things work as well as they do. But that’s because there’s been processes like Six Sigma to make sure that they do.

Kira Bindrim: After the break, Six Sigma takes on the world.

[ad break]

Six Sigma certification frenzy

Kira Bindrim: So before the break, we were talking about how GE got really invested in Six Sigma, and you started to talk about kind of the like cottage industry that blew up around it. Talk a little bit more about what that actually looked like.

Oliver Staley: So an easy way to think about it is like in 1999, there were zero books with Six Sigma in the title, I think, in 2000, there were three and in 2001, there were like 24. And, you know, there are Six Sigma for dummies, Six Sigma for healthcare professionals, Six Sigma for dog walkers—like there was like this explosion of Six Sigma related books, and a parallel explosion in courses and trainings to get you and your company up to speed. And for someone looking for a job, it became like an imperative that you have Six Sigma in your resume.

Kira Bindrim: Who is the keeper of the Six Sigma lore, like is there no central authority?

Oliver Staley: There really isn’t. And that is, I would think, for the people who are invested in it, I think it’s a big problem, because it really, is anyone who can put out a shingle and claim to be a Six Sigma instructor. You could take courses at various universities, but you could, if you type into Google, Six Sigma training, you can get some online course, for like $60, and it may or may not be any good. And there’s no authority or a creditor to tell you it is or it isn’t.

Kira Bindrim: How prevalent is Six Sigma right now?

Oliver Staley: If you are an engineer, you are either using Six Sigma or something like Six Sigma. The statistical analysis of your manufacturing and using data to sort of understand what is and isn’t working and how you’re making something, I think that’s fairly standard now.

Kira Bindrim: In the course of your reporting, have you talked to Six Sigma acolytes, or people whose perception of it has changed over time in some way?

Oliver Staley: I think the people who were invested in it recognize that it got out of control, and that it began to be applied to job functions where there wasn’t any real application for it. And I think, if they’re honest with themselves, they would recognize that like, you don’t really need to Six Sigma a sales person’s role. You know, there are certain functions that it makes a lot of sense for and a lot of functions it doesn’t make any sense for.

Does GE still use Six Sigma?

Kira Bindrim: what is the process of GE losing faith in Six Sigma?

Oliver Staley: Well, Jack Welch was replaced by Jeff Immelt, but, you know, I don’t think Immelt was as as much of a believer as Welch was but it was a “if it’s not broke, don’t fix it” kind of thing. One of the not very hidden secrets about General Electric is they were really a financial services company that also made stuff. Basically they were they were lending money, and that all collapsed during the financial crisis. And Six Sigma did not help them recover from that. So Six Sigma really started to wither at General Electric, and Immelt started searching for other systems and theories that could help rescue the company.

Kira Bindrim: So General Electric is now going to church on Easter and Christmas only.

Oliver Staley: Yeah, if. There mouthing the hymns.

Kira Bindrim: On the one hand, like over the past 20 or 30 years, it’s easy to imagine that a management theory that worked in the 90s might be relevant today, like the fundamentals of running a business are not that dramatically different. But on the other hand, like it does feel outdated, almost hearing about it today, or just not as relevant. What do you what do you kind of make of these management theory ebb and flows?

Oliver Staley: Well, I think I think management theory fits the business culture of the time. And so what what happened essentially over the last 20 years is that industrial manufacturing became less and less sexy, and software and engineering and the internet sort of became the business world, and all the energy and excitement, and business is around online and software. The emphasis became much less on quality control, and much more on innovation, and disruption, and speed. And the, you know, the famous Mark Zuckerberg quote, “move fast and break things” is kind of the, in many ways, the opposite of Six Sigma, which is “move slowly and and make sure nothing breaks.”

Kira Bindrim: So in some ways, like the process of creating the iPhone, making the iPhone in a production sense, is logically Six Sigma-ed, the process of developing iOS is maybe not logically Six Sigma-ed, might even be hurt by it.

Oliver Staley: Yeah, I think that folks now think that that kind of methodical statistical analysis gets in the way. But a manufacturing engineer would probably recoil at that idea. Like, they want to make sure everything works perfectly before they start running the assembly line.

Kira Bindrim: In our reporting at Quartz, we are talking a lot about like stakeholder capitalism, and sort of the folding into company values of things that aren’t just about the bottom line, or the actual success of the company from a financial perspective. Do you think that we will see a management theory that speaks to that, that’s almost like more empathetic or inclusive, or internally rewards people for doing things that sort of lead to that kind of success?

Oliver Staley: Possibly. We might already be in the midst of that forming. Management theories are only as good as the people who are employing them, you know, and then it starts with the CEO. And if the CEO is not buying in, then that theory is gonna wither and fade. Yeah, I do think you could construct a management theory based on a more inclusive and holistic view of the world and your stakeholders. And, you know, that’s not just about rewarding shareholders. But whether that’s durable, you know, the proof is in the pudding.

Kira Bindrim: It seems like it really comes down to how dogmatic you are about it and for how long. Because ultimately, you know, the world around you changes, and if your company is so stuck on one management theory that it can’t move forward with the world, that’s going to be a problem.

Oliver Staley: Yeah, it’s interesting, because I think all companies, especially old ones, like to refer to their history and tradition and their values. And yet, I think companies are as interested in their values and their tradition to the extent that they are useful for making money today. And when those are no longer useful, they move on to something new.

Kira Bindrim: Okay, I have one more question for you. What is your favorite fun fact about Six Sigma?

Oliver Staley: This is a surprise question. So I didn’t come prepared with a fun fact about Six Sigma

Kira Bindrim: You’re not just full of fun facts about Six Sigma?

Oliver Staley: What I think was interesting is how closely it was tied to General Electric. And that as General Electric began to slide, first slow and then very quickly, Six Sigma sort of fell out of favor. If General Electric maintained its success for another decade or two, Six Sigma may have maintained its relevancy in the business culture.

Kira Bindrim: Super interesting. See, that’s a fun fact. Thank you for joining me Oliver.

Oliver Staley: Thank you for having me.

Kira Bindrim: That is our obsession for the week. This episode was produced by Katie Jean Fernelius. Our sound engineer is George Drake, and the theme music is by Taka Yasuzawa and Alex Suguira. Special thanks to editors Oliver Staley and Alex Ossola in New York. If you liked what you heard, please leave a review on Apple podcasts or wherever you’re listening. Tell your friends about us, ask them who has the most colorful belt collection, and then listen to the podcast together. Then head to qz.com/obsession to sign up for Quartz’s weekly obsession email.