NASA is shaking up its bureaucracy to shoot for the Moon

This week, NASA split its human spaceflight division in two.

This week, NASA split its human spaceflight division in two.

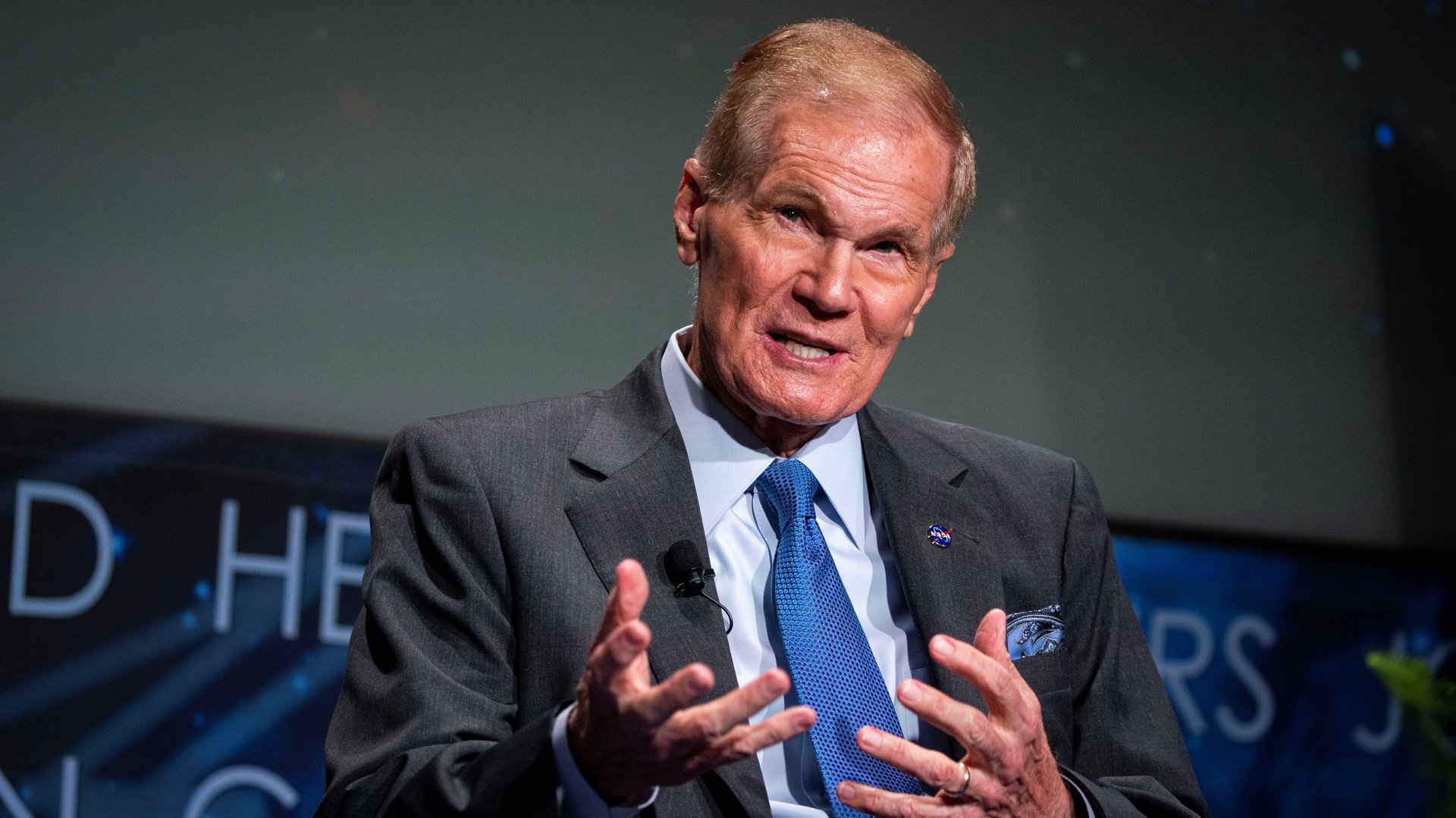

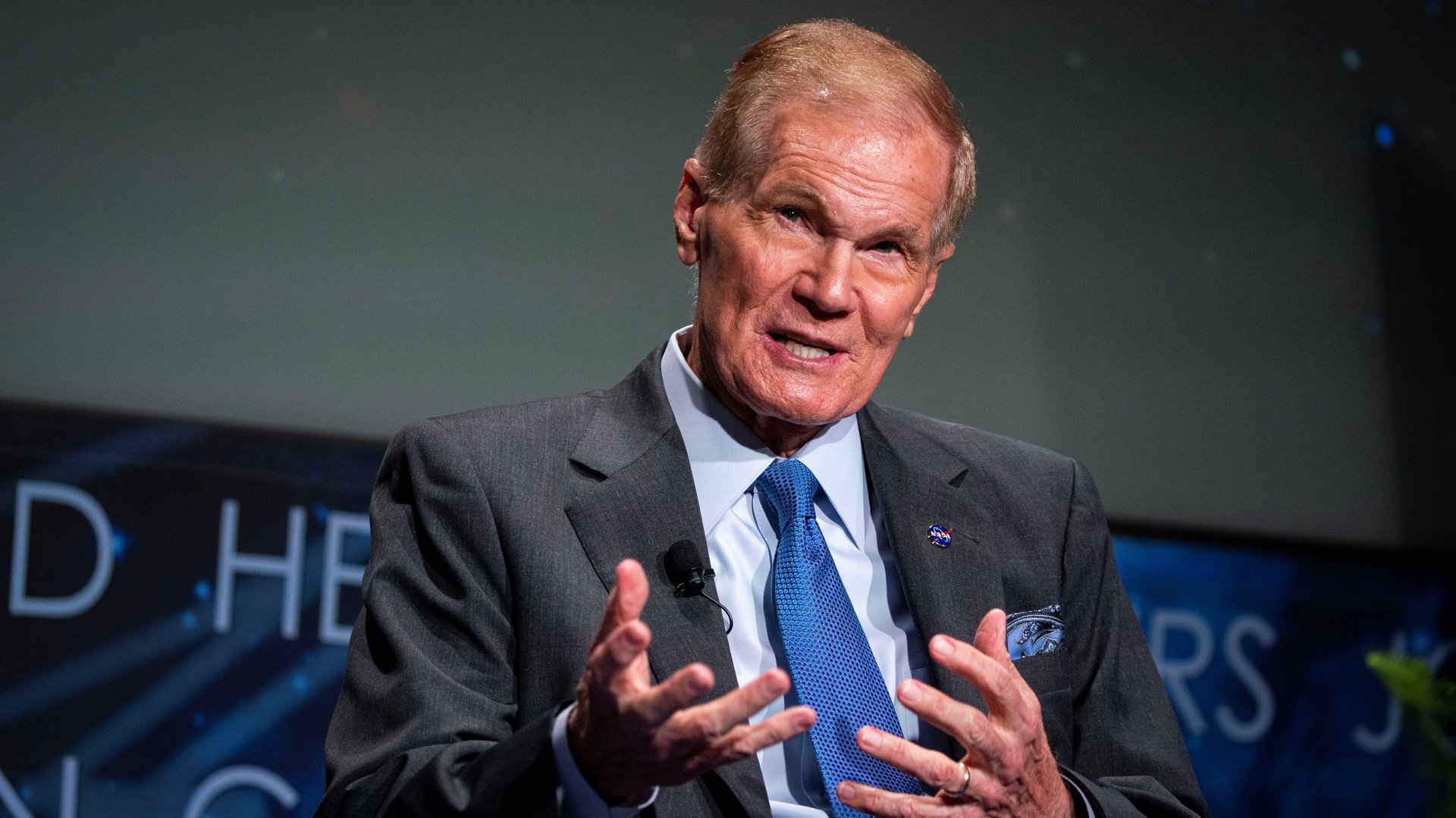

Administrator Bill Nelson said one directorate would focus on operational activities in space, and the other would develop new technologies and concepts for future missions. In effect, the move separates NASA’s work in low-Earth orbit from decisions about how the space agency will return astronauts to the moon through the Artemis program.

This is not an unusual structure on its face; a similar organization was used by NASA prior to 2011, and the US military separates the people responsible for developing and testing new technology from those who operate it.

Instead, the decision is controversial because of its context: It removes responsibility for plotting out the Artemis mission from associate administrator Kathy Lueders, who previously oversaw all human spaceflight programs, and now will focus on operations. A former NASA official, Jim Free, came back from the private sector to take on the job of developing plans for going to the moon and Mars.

The troubled history of Artemis

During the Trump administration, NASA set a goal of landing astronauts on the moon in 2024. The date is seen as arbitrary, explained either by the White House’s political purposes or, per NASA, to create deadline pressure to accelerate the mission. But Congress has never supported that deadline with necessary funding, and NASA has yet to explain how it will achieve its goal. Free is arguably the fifth person tasked with doing that.

In 2019, the previous NASA administrator, Jim Bridenstine, attempted a similar reorganization to put deep space exploration under an executive named Mark Sirangelo, but Congress frowned on the plan’s cannibalization of other NASA funding and Sirangelo resigned. Then Bridenstine fired Bill Gerstenmaier, an associate administrator, over the slow pace of lunar development. Former astronaut Ken Bowersox took on the job on an acting basis, and then was replaced as the top human spaceflight official by Doug Loverro, a Pentagon space expert.

But Loverro resigned over his handling of Artemis contracts, after it emerged that he improperly assisted Boeing’s plans to bid on lunar landers, prompting a grand jury investigation. That led to Lueders taking the job. But after she awarded a lunar lander contract to SpaceX, Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin challenged her decision and took NASA to court, adding months, at least, of new delays.

Does an organizational change mean a policy shift?

Lueders is respected inside and outside of NASA for seeing through the space agency’s work with private companies to fly cargo and astronauts to the International Space Station. The Artemis architecture has adopted some components of those partnerships, hiring private companies to put robots on the moon, ship supplies there, and build the landers that will carry astronauts to the surface.

Now, she’s been replaced by Free, who boasts decades of NASA experience, but mainly in traditional NASA programs, including Orion, the over-budget spacecraft that is expected to take astronauts from Earth to lunar orbit. Deals that guarantee profits and include extensive NASA requirements are beloved by contractors and lawmakers who prioritize in-district spending by the space program. Some observers, including NASA employees, see the split as a sign the space agency is turning away from the only model that has delivered working hardware in recent years.

Nelson denied that this is the case, insisting that the decision was “obvious” because the portfolio of human spaceflight activities, about half of NASA’s annual budget, could not be managed by one person. Lueders and Free said they would, by necessity, work closely together, but ultimately the path forward will be set by the official developing plans and issuing first contracts.

Defining lunar landings down

Observers of the space program had expected Nelson to deliver some of kind of update on the return to the moon, perhaps the long-awaited acknowledgment that a moon landing in 2024 isn’t feasible. Asked about timing, he offered a sleight of hand.

“Artemis 1 will be at the end of this year or the first part of next year,” he said. “Then we are going to the moon with humans in late ’23 or early ’24. Then, if you have a coin, you can flip it, as to what’s going to happen with the legal wrangling that’s going on right now…once we have answers about that, we can answer about Artemis 3 or Artemis 4.”

The second Artemis mission, to fly astronauts in an obit around the moon, was originally planned for 2022 or 2023, ahead of Artemis 3, which was to put humans on the surface in 2024. Nelson appeared to suggest that NASA would act as if the orbital mission fulfilled its initial proposal. I asked if it is NASA’s view that an orbit around the moon would fulfill the agency’s promise to land by 2024.

“Do you remember Apollo 8?” the 78-year-old former senator replied, referencing the 1968 test mission. “It was humans going to the moon for the first time…the pictures of the moon looking back at Earth, a perspective we had never had, that was a major achievement. After Apollo 17, we have not been back to the moon. We are, in Artemis 2, [launching] a mission that will be…way out beyond the moon, further than any human has ever been.”

It wasn’t quite an answer, but it’s a far from the original promise of Artemis as articulated by Nelson’s predecessor: “What we don’t want to do is recreate Apollo.”

A version of this story originally appeared in Quartz’s Space Business newsletter.