The father of 3D printing says it’s overhyped

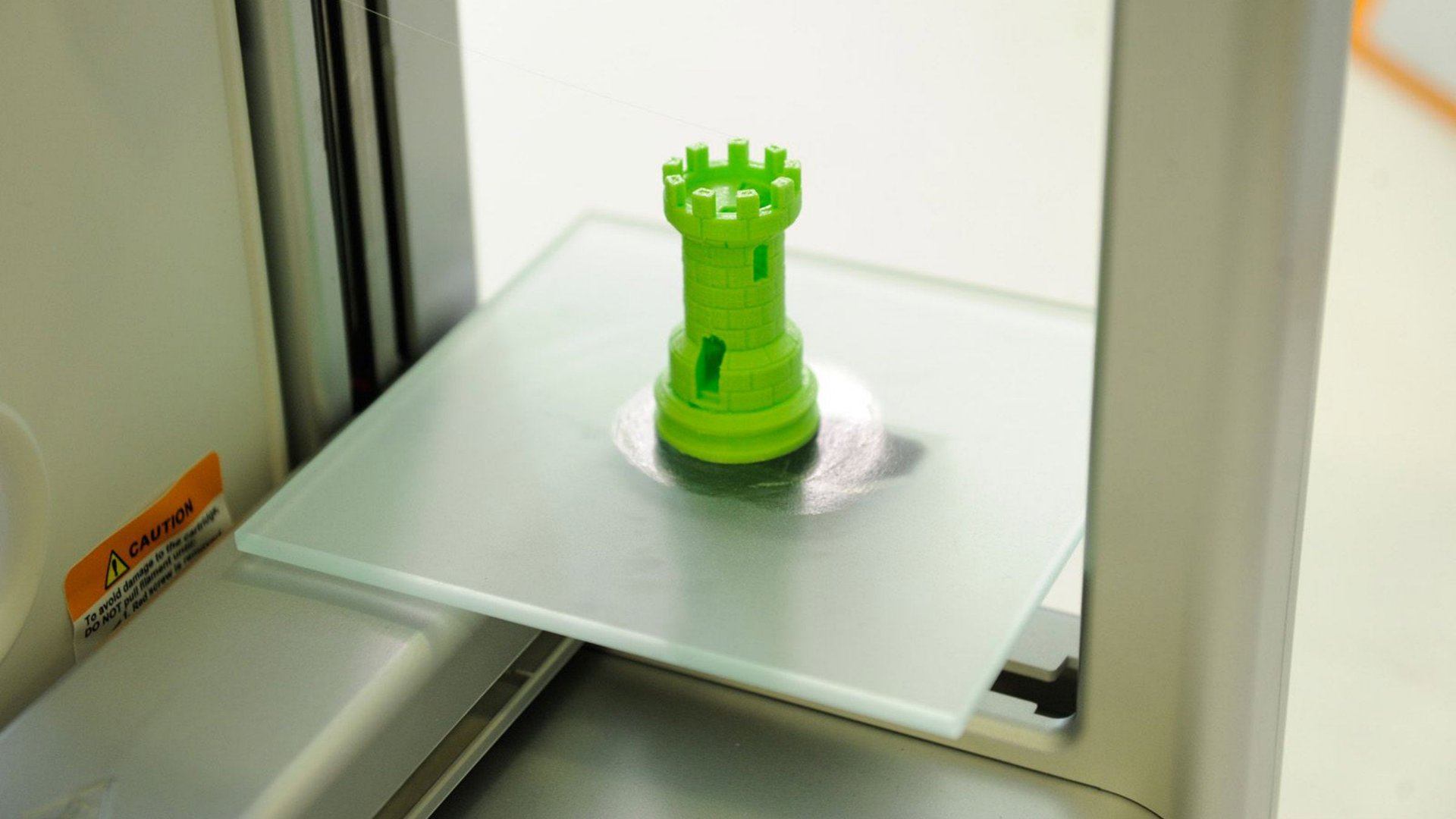

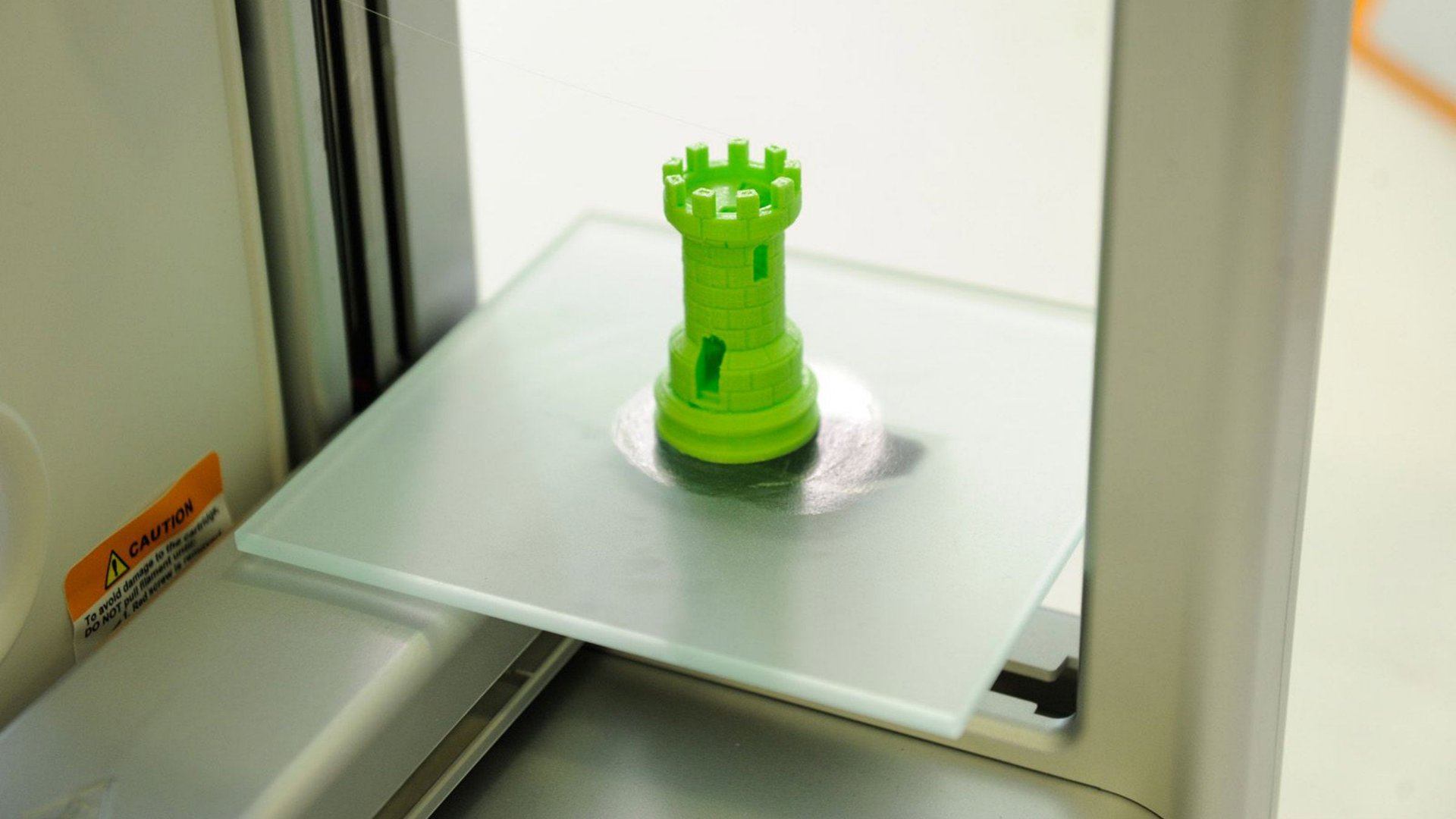

In the 31 years since an engineer named Charles Hull invented 3D printing, it has gone from a way for car companies to quickly prototype plastic parts to something that’s touted as a technological cure-all. Meanwhile, the price of consumer 3D printers has come down dramatically, and last month, office-supply retailer Staples opened a handful of “experience centers” in Los Angeles and New York City where customers can try out the printers before buying them.

In the 31 years since an engineer named Charles Hull invented 3D printing, it has gone from a way for car companies to quickly prototype plastic parts to something that’s touted as a technological cure-all. Meanwhile, the price of consumer 3D printers has come down dramatically, and last month, office-supply retailer Staples opened a handful of “experience centers” in Los Angeles and New York City where customers can try out the printers before buying them.

The claims for the technology have become increasingly grandiose. Proponents say it will be routinely used to build homes, food, and human tissue. 3D printing ”has the potential to revolutionize the way we do almost everything,” US president Barack Obama declared at the 2013 State of the Union.

Maybe—but not yet. And unless you’re an engineer, it’s hard to tell the hype from the reality. So after Hull was nominated for the European Inventor Award from the European Patent Office (he’s up against the inventors of the QR code), we asked him to explain what the biggest fans of 3D printing get wrong, what to do about 3D-printed guns, and where some of the technology’s hidden applications might lie. Here are some extracts of the conversation.

Quartz: 3D printing has become hugely hyped. It’s now shorthand for a kind of techno-utopian thinking. What do you think about some of the rhetoric surrounding it?

Charles Hull: Some writers and people who talk about 3D printing get over-enthused. Most of the stuff they talk about will happen someday—eventually. But there’s the here-and-now and the near-term future, where a lot of that stuff is definitely hype and won’t happen. I’m very steeped into what can happen in the relatively near term. So I just tend not to pay too much attention when the hype gets too obscure.

There are going to be tremendous advances in manufacturing capabilities with 3D printing, but you need to understand that it’s in concert with other advances in automation and computing and so forth. So 3D printing isn’t necessarily the only component. There’s a lot of things in the digital-manufacturing world that are advancing together to really improve local manufacturing. Sometimes 3D printing is used as a substitute word for the whole digital-manufacturing field. And you kind of have to be in the manufacturing realm to understand or appreciate that. It may be OK that 3D printing is used as a shorthand, but it’s only a part of a broader movement.

Also, how soon will all those advances in manufacturing happen? The answer is that it’s a very evolutionary process with lots and lots of relatively minor advances. So from a day-to-day working in the field, it’s more working on the particulars without too much vision for the longer-term totality of it.

When you hear stories about guns being made by 3D printing, or speculation about printing human tissue, does that concern you at all?

Yeah, it’s a concern. That’s where the people who come up with and enforce the public-safety laws, that’s their concern and responsibility. 3D printing is probably not the best way to make a gun these days. If somebody wants to make guns, there are lots of technologies to do it with. I think the fact is that people who want to make guns now can make guns. It’s maybe the responsibility of the people who police legal issues to adapt to the technology.

I’m curious about some of the less glamorous but maybe more useful applications of 3D printing.

You might have seen the Google Ara phone that’s being developed. All the enclosures for the modules of the phone will be 3D printed, with the idea that they can be customized and individualized for each person. So everybody can have a phone that they themselves helped style. Maybe that actually is glamorous, but it’s more along the lines of what 3D printing can do, because as you get the technology into manufactured applications, then complexity and customization are freed. But my perspective is improving the production speed of 3D printing and getting all the hardware and software established so this can happen.