The Publicis-Omnicom mega-merger unravelled for entirely predictable reasons

The $35 billion merger of advertising giants Publicis and Omnicom is no more. The companies called off the deal late last night in a terse statement (pdf), saying that despite the botched combination they “maintain a great respect for one another.”

The $35 billion merger of advertising giants Publicis and Omnicom is no more. The companies called off the deal late last night in a terse statement (pdf), saying that despite the botched combination they “maintain a great respect for one another.”

This respect was hard to see during the merger integration process, with a wide range of gripes between the French and American groups now leaking out. Tax issues, culture clashes, and the balance of management control in the proposed “merger of equals” have loomed large since the deal was announced last July and reckoned to wrap up by the end of 2013.

Publicis boss Maurice Lévy and his Omnicom counterpart John Wren (pictured above) were slated to run the combined group as co-CEOs for 30 months after the merger. But in a conference call today Lévy, who is 72 years old, said that he would have been happy to step down earlier, leaving Wren, 60, to run the group on his own. This meant that Publicis was pushing for its CFO, Jean-Michel Etienne, to become finance chief of the combined company.

This was seen as the crucial factor in whether the group would follow Publicis’s more centralized business model or Omnicom’s looser federation approach. But the groups couldn’t decide on a CFO—a seemingly mundane sticking point for an industry built on big egos and creativity—before they called the deal off. “You cannot have a merger of equals where you have the CEO, the CFO, the General Counsel coming from the same company,” Lévy said.

Another one bites the dust

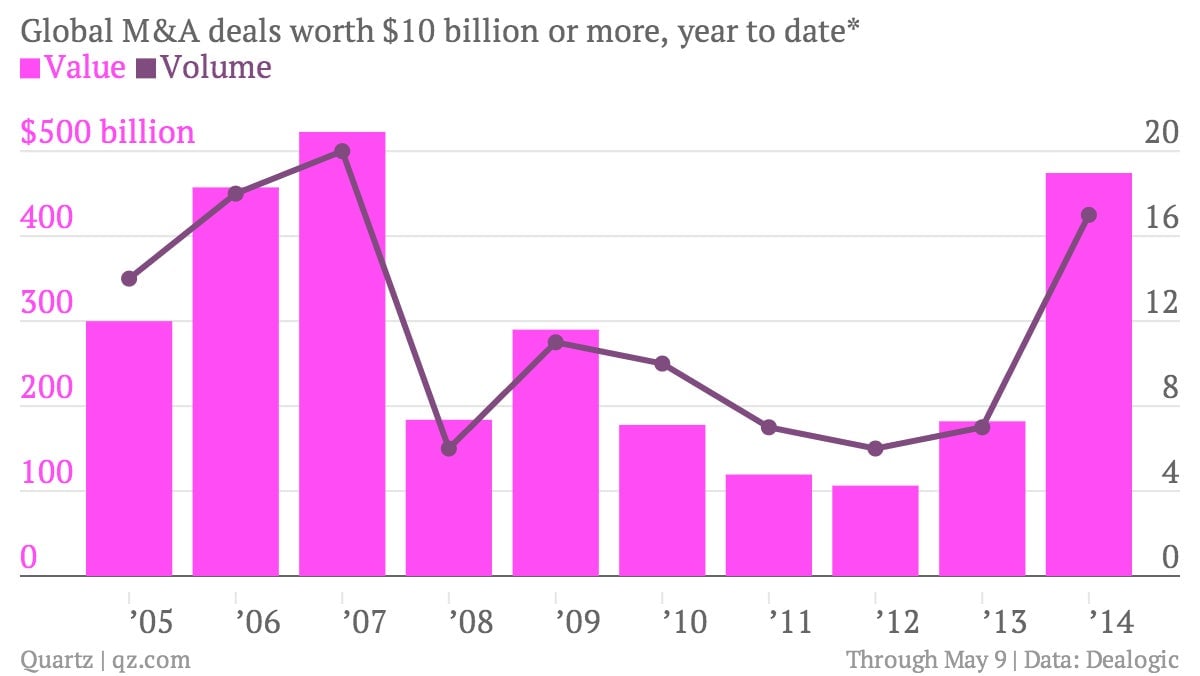

Notwithstanding the ins and outs of this particular deal in this particular industry, don’t say that we didn’t warn you. The history of mega-deals is not a happy one, as we wrote recently. And yet the urge to merge is rising; the number of deals worth more than $10 billion so far this year is approaching the all-time record set in 2007:

On the other hand, the number of cancelled deals is also up 30% on a year ago:

“Transformational” deals appeal to the empire-building instincts of company bosses, but they rarely pay off as routinely as smaller “bolt-on” acquisitions where the balance of control and power between parties is more clear. Martin Sorrell, who runs WPP, Publicis and Omnicom’s biggest rival, has been quick to point this out.

Sorrell told Reuters, sarcastically, that he was a big fan of the Publicis-Omnicom merger, since it meant the equally-sized rivals would be distracted “fighting with one another about who’s running the company.” According to filings, WPP spent £221 million ($374 million) on 62 acquisitions last year; it bought another 20 companies in the first quarter of this year, and expects to spend £300-400 million on “strategically targeted small and medium-sized acquisitions” in 2014.

Lévy said in a statement (pdf) that the decision to terminate the merger with Omnicom was “neither pleasant nor an easy one to make.” But it’s telling that the two companies’ share prices are little changed so far today, as if the cancelled merger didn’t come as too much of a surprise to the markets.

But the fact that it took them nine months to decide to scrap the deal might discomfit the bosses behind other mega-mergers, like last month’s proposed tie-up between construction giants Holcim and Lafarge. Will they too take months to realize that bigger isn’t always better?