Why Africa’s debt downgrades are good news for Africans

Is the honeymoon over for Africa’s debt markets? So said the Financial Times last week (paywall). It argued that the region’s economic boom is coming back to bite it as African governments that ran up large fiscal deficits are now feeling the pain of debt downgrades. That same week, Standard & Poor’s announced that “the heydays of bond offerings from newcomers or from frontier markets, like the African issuers” are over.

Is the honeymoon over for Africa’s debt markets? So said the Financial Times last week (paywall). It argued that the region’s economic boom is coming back to bite it as African governments that ran up large fiscal deficits are now feeling the pain of debt downgrades. That same week, Standard & Poor’s announced that “the heydays of bond offerings from newcomers or from frontier markets, like the African issuers” are over.

But the other way to look at it is that this is exactly what’s supposed to happen.

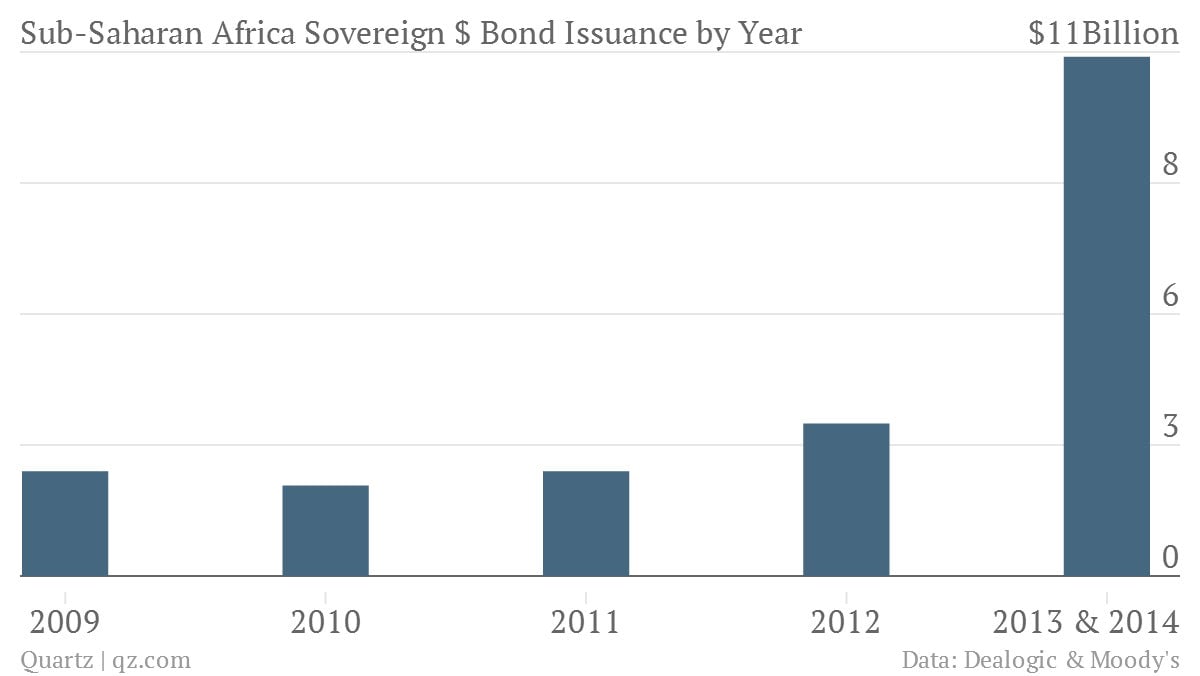

Certainly there’s been a boom in borrowing. Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has issued more sovereign dollar bonds in the past 15 months than the last four years combined. In 2013 and the first quarter of this year, SSA countries issued $8.1 billion in dollar-denominated eurobonds. For bonds announced as well as issued, the figure is $10.9 billion, including Kenya’s maiden launch, anticipated in August.

In fact, you might already be holding SSA bonds in your investment portfolio. Big institutional investors like PIMCO and Fidelity have been increasingly buying them, attracted to higher yields, improved sovereign risk profiles, and a new regional asset class to diversify their portfolios.

Perhaps even more important than what the bonds offer investors, though, is the possibilities they create for the countries that issue them.

Though SSA has been making headlines as the world’s fastest growing region after emerging Asia, much of the earlier two-decade wave that became the globalization of finance passed it by. The entire continent has 29 stock markets, but most of them have under 40 total listings. Before 2011, South Africa aside, SSA’s total stock market capitalization was less than $100 billion, around double that of Starbucks today. Africa’s local-currency domestic bond markets are still nascent.

Connecting to global bond markets gives African governments, which are struggling to deliver infrastructure to match their economic growth and emerging middle classes, a source of financing that isn’t private loans or foreign aid. Nigeria is funding greater electricity output with its $1.5 billion issuances. Kenya will use its 2014 eurobond money to upgrade power, roads, and seaports. Zambia plans to spend on improved healthcare and railways.

Some governments have been able to get national credit ratings for the first time as they’ve become more accountable and transparent, giving them access to the bond markets. “This new SSA bond volume has been greatly facilitated by improved economic conditions and governance, which has supported more governments meeting conditions to receive sovereign credit ratings,” Moody’s senior Africa debt analyst, Aurelien Mali, told Quartz.

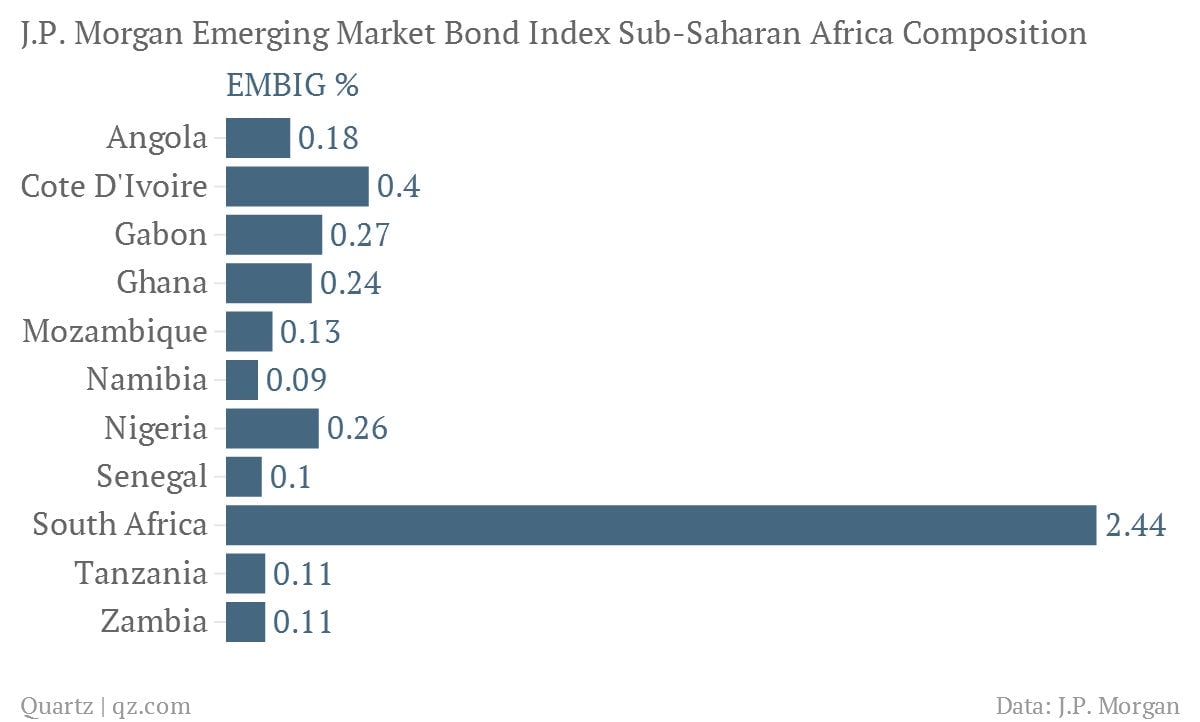

African governments are also benefiting by being included in standard indicators, like JP Morgan’s Emerging Market Bond Index (EMBIG). “EMBIG is a benchmark index. The moment these governments make it to the index they are no longer as exotic as they used to be,” says Pimco’s Francesc Balcells, an emerging-market fund manager.

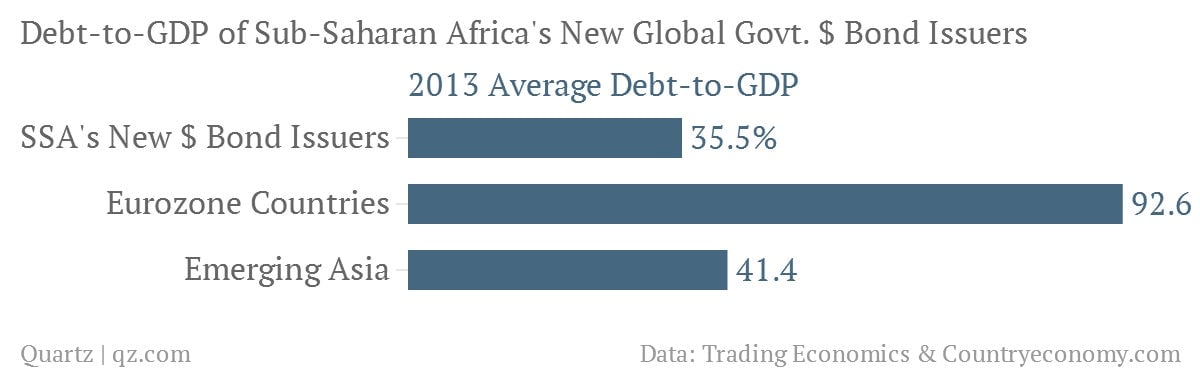

Improved public finances have also proven vital. While richer countries were on a pre-financial crisis leverage binge, Africa had weathered much of its own debt calamity. In debt-to-GDP terms (though admittedly, perhaps not in debt-to-tax-revenue terms), fiscal houses of many SSA issuers are in pretty good shape compared to the rest of the world, especially euro-zone countries like Spain and Greece. There are many ways for investors to assess sovereign bonds, says Ballcells, but one of the most basic—comparing the yield to the debt-to-GDP ratio—makes many of the EMBIG names “relatively attractive.”

The risks of easy money

Still, it’s no surprise that several economists, most notably Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz, have sounded alarms to Africa’s sovereign borrowing spree. They warn that bonds impose fewer conditions and monitoring on governments than multi-lateral lending from other countries. And they point to possibilities of a new African debt crisis, as both deficits and—consequently—borrowing costs rise.

That’s certainly a risk. A good example is Zambia, which issued its first bonds at 5.375% less than two years ago. Since then its finances have deteriorated and investors in those bonds have lost money. It had to price its latest issue at 8.625% last month.

But the naysayers to African debt have yet to suggest better ways for Africa to pay for crucial infrastructure. And Zambia’s problems also show that there is no better way to foster accountability than connecting governments to national credit ratings and the scrutiny of global bond markets. Sovereign credit ratings and variable bond yields provide instant, and economically tangible feedback. Global business headlines love a downgrade. Too much corruption or bad economic policy will cause investors to dump their bonds and drive up borrowing costs. The Nigerian government realized this too during its recent Sanusi central bank whistleblower corruption scandal, which sparked widening spreads on its new bonds, a drop in its stock market and currency, and a Standard & Poor’s sovereign credit downgrade.

There will certainly be ups and downs; some SSA nations will find it difficult to meet investor and fiscal needs. But European countries like Greece, only just getting back into the bonds game, face the same problems. And to wean themselves off foreign aid and move from “frontier” to “emerging” market status, countries need sovereign debt markets.

Moreover, connecting to sovereign bond markets and credit ratings could improve SSA countries’ markets for other kinds of capital, like stocks and corporate and municipal bonds. The African Development Bank is working on highly anticipated Diaspora Bonds, funded by increasingly affluent African expats. Remittances from these Africans overseas may already represent the greatest source of external funding for SSA, exceeding both foreign direct investment and foreign aid.

Sub-Saharan Africa can surely benefit from its new international debt financing. And just like other regions of the world, its governments could benefit from the lesson that hell hath no fury like a bond investor scorned.