Are US broadband providers already violating new open internet rules?

US telecommunications regulators just approved preliminary rules intended to protect an open internet and ensure investment in its improvement.

US telecommunications regulators just approved preliminary rules intended to protect an open internet and ensure investment in its improvement.

The proposed rules attempt to prevent discrimination while allowing some content to travel over paid “fast lanes.” Broadband companies say the rules interfere too much in their business; advocates for a more open internet say the regulations don’t do enough to protect consumers. Both will spend the next four months lobbying regulators before they approve a final rule in the fall.

One important moment at today’s hearing was when Tom Wheeler, chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, explained the standard of “commercial reasonableness” that would protect consumers from cable company incentives to degrade internet service: “If a network operator slowed the speed below that which the consumer bought, it would be commercially unreasonable and therefore prohibited.”

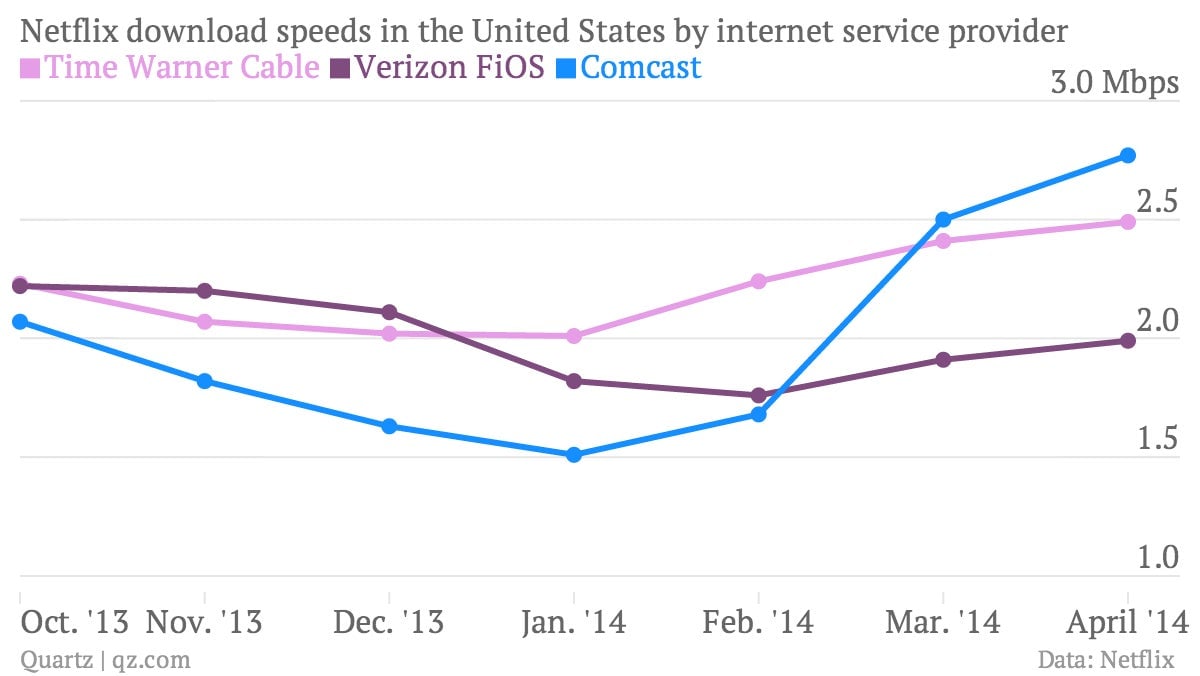

That’s going to be a tough standard to enforce. During the course of its dispute with Netflix over carrying the video streaming service’s traffic, download speeds for Comcast customers fell, but when Netflix agreed to pay for access to Comcast’s network in February, they shot back up:

According to Comcast’s website, its slowest broadband internet plane is marketed at a speed of 3 Mbps; the rest of its plans range from 6 Mbps to 150 Mbps. That suggests that many Comcast customers were receiving “commercially unreasonable” service, especially before it reached a deal with Netflix.

The difference between advertised speeds and what consumers actually receive is a constant bug-bear in the internet business, in part because so many different actors affect internet access and because testing speeds involve an array of considerations about when and how long such tests should last. And, if you read your broadband contract, you’ll find it is full of hedges and caveats about what you can expect compared to what you think you bought.

The FCC already has procedures for this: In September 2012, it found that Comcast was providing advertised speeds of 3Mbps 102% of the time—which might surprise Netflix customers using Comcast, whose average download speed, according to Netflix, was 2.11 Mbps the next month. But not every company met this standard: Even big ISPs like AT&T and Time Warner Cable failed to meet their advertised speeds in certain tiers. Would that put them in violation of the new net neutrality rules?

It’s possible that the most important part of these rules won’t be the standards that companies must adhere to, but the new requirements for what data they must reveal about their technical and business practices. FCC access to internal data about network performance, will be key to making sure that the new paid “fast lanes” don’t result in the anti-competitive and anti-consumer consequences feared by open internet advocates.