Despite the pay gap, women in the US now have as much job security as men

American women may still be underpaid, but they now have similar job security to men. In the 1980s, most women had much lower tenure on their job compared to men of a similar age; few women had very long careers with any one employer. But since then tenure rates have converged, even if wages haven’t. That’s because the economy is changing for both genders—career-long employment is more of a rarity but women have formed more stable work relationships.

American women may still be underpaid, but they now have similar job security to men. In the 1980s, most women had much lower tenure on their job compared to men of a similar age; few women had very long careers with any one employer. But since then tenure rates have converged, even if wages haven’t. That’s because the economy is changing for both genders—career-long employment is more of a rarity but women have formed more stable work relationships.

The typical career path of the American worker has changed in the last 30 years. Despite the recent recession, worker mobility—the probability that you will change jobs each year, either through firing or quitting, has been declining, which suggests that Americans are staying in their jobs for longer. This has sparked concerns of a more stagnant labor market bereft of the dynamism and skill formation that once existed. But just because people change jobs less frequently doesn’t mean they are building longer careers with their employers. Median tenure, the number of years on the job has been fairly stable, from 1983 to 2008, hovering around five years, before increasing a small amount following the recession. But economy-wide tenure masks two very different stories for men and women.

Since the 1980s the number of years men worked on their jobs fell, while women’s median tenure increased. This is not totally surprising. In the 1970s and 1980s, more young women entered the labor force with longterm career ambitions that did not preclude having a family. Even in 1980 the labor force participation rate for women between age 25 and 54 was just 64%; now it is 74%. As gender norms changed so did laws that helped keep women in the labor force. Maternity leave became more popular on a state-by-state basis in the ‘70s and ‘80s before it became federal law in 1993.

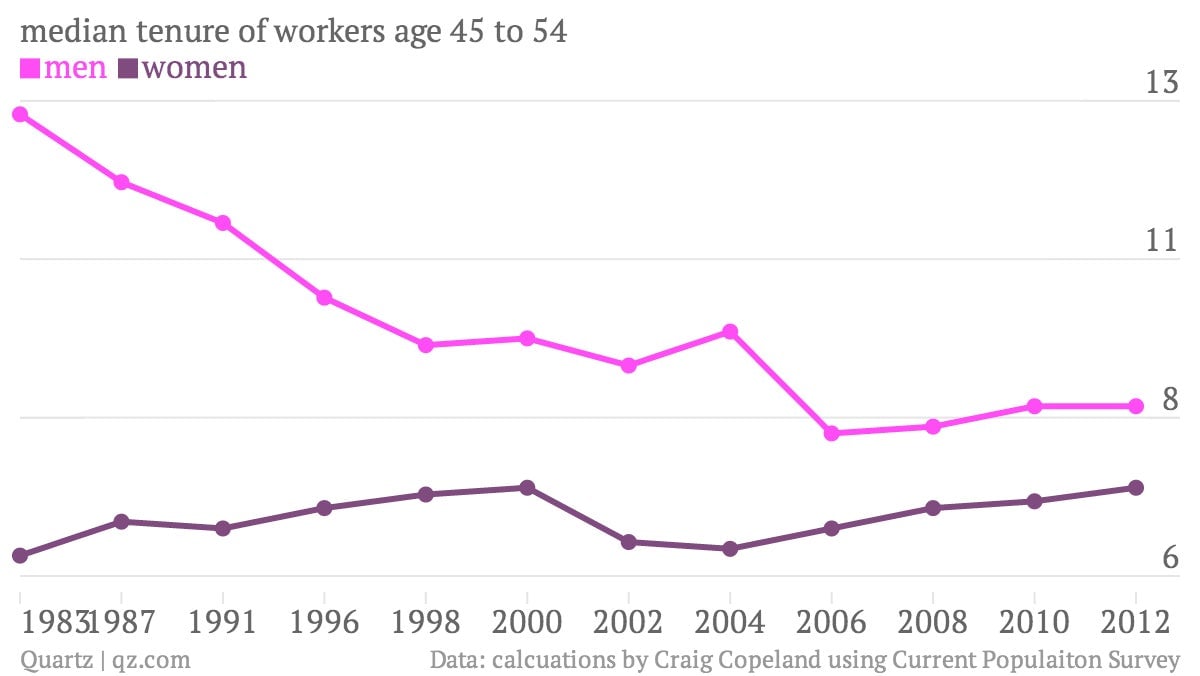

In 1983, just 4.9% of women had more than 20 years of tenure at their job compared to 12.4% of men. But by 2012 these rates converged—10.10% of women and 11.9% of men had been in their jobs for more than 20 years. It’s remarkable that male tenure fell considering the population has aged more than seven years, since tenure normally increases with age. The decline in tenure is more apparent when you account for age. Median tenure of men between ages 55 to 64 was 15.3 years in 1983. It fell nearly five years to 10.7 years by 2012. Men ages 45 to 54 also lost five years of tenure. Meanwhile average tenure among women rose slightly (about one year) for all age groups.

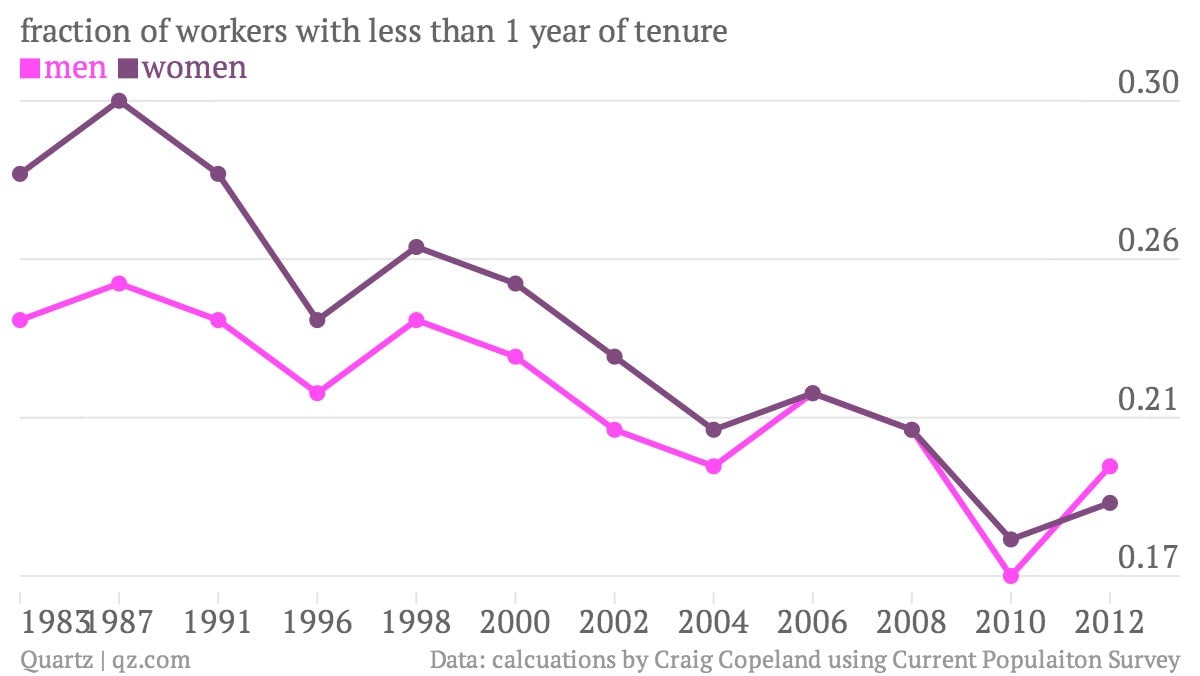

So how can we reconcile stable tenure with the fact that people change jobs less frequently? In part, it comes from women spending more time in their jobs, which is driving the economy-wide mobility rate. But it also reflects differences in how we work. It used to be young people, especially women, would often go through different jobs that didn’t last very long. In the 1980s, more than a quarter of workers were in their job for less than one year. But now, Americans, both women and men, are less likely to leave their job after less than a year.

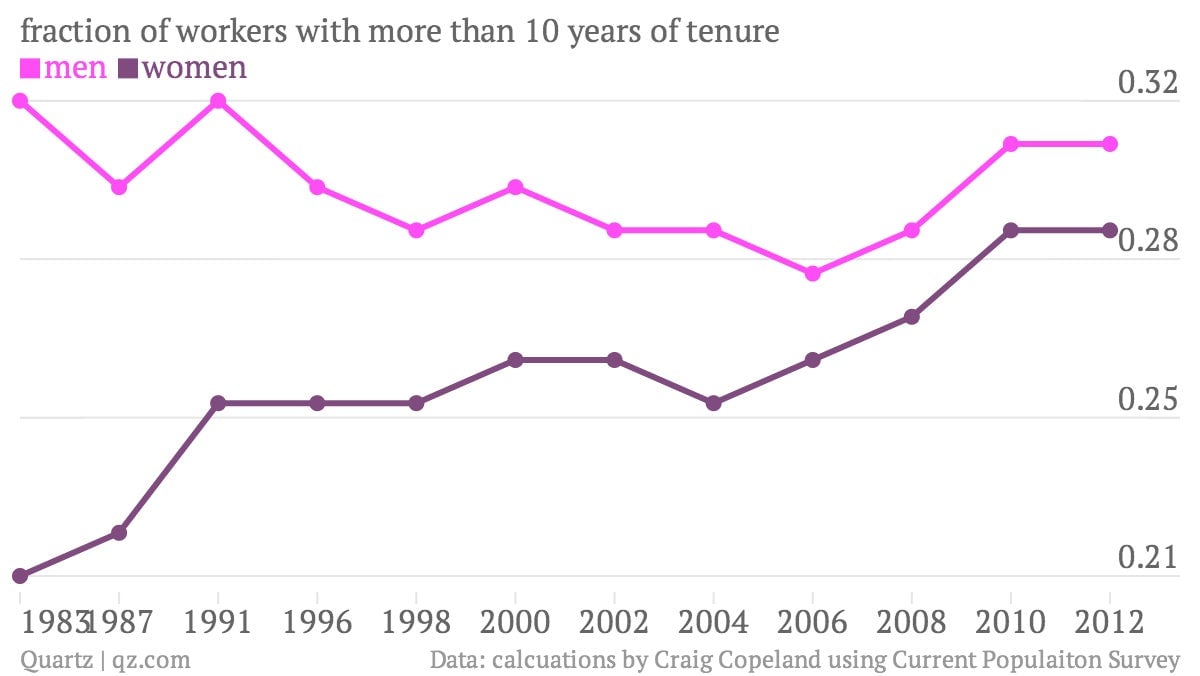

For men at least, once they found a longer-term job, it tended to stick. But that is less likely to be the case today. The evolution of tenure diverges for men and women when you look at very long rates of tenure. The figure below is the fraction of workers with more than 10 years on the job.

Up until the recession, long tenure was becoming less common for men but much more common for women. The rates are now similar across genders. Male tenure may be falling and women’s is increasing, but women will probably not overtake men. The figure below controls for the aging population. It shows median tenure for people age 45 to 54, the age when people normally have settled into a long-term job.

Women’s tenure has increased but lately seems to be leveling off. Both very short and very long-term employment has fallen out of fashion. That suggests that the dynamism in the labor market is not dead because people are not necessarily stuck in their jobs for too long. Workers still change jobs, they just stay in them a little longer than they used to and that’s probably a good thing. Few skills are learned in less than a year of work—it normally signals a bad match. It seems that we are getting better at matching workers to companies and then the worker moves on after a few years. That could be because the labor market rewards skills that require several years at a few different jobs, rather than a long career at just one job. It also probably reflects a shift away from manufacturing jobs, which encouraged very long employment though benefits.

It’s remarkable that the gender wage gap started to narrow staring in the late 1970s. But it’s leveled off and hasn’t gotten much smaller since the mid-1990s. But during the same period, the tenure gap did continue to narrow—it’s only flattened since the recession. We expect seniority to translate into higher pay, but the fact that the tenure gap narrowed while the pay gap hasn’t suggests that it’s still not the case for women.