A history of design innovations emerging from health crises

It may seem strange to hold an exhibition about design solutions for health crises while the world is still in the throes of one. Such survey will likely be incomplete, and lack the perspective gleaned with time and distance from this latest event. But somehow, Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics, which opened at New York’s Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum around the time covid’s omicron variant emerged in the US, subverts this premise. Its immediacy and iterative spirit is in fact what makes the show worth seeing.

It may seem strange to hold an exhibition about design solutions for health crises while the world is still in the throes of one. Such survey will likely be incomplete, and lack the perspective gleaned with time and distance from this latest event. But somehow, Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics, which opened at New York’s Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum around the time covid’s omicron variant emerged in the US, subverts this premise. Its immediacy and iterative spirit is in fact what makes the show worth seeing.

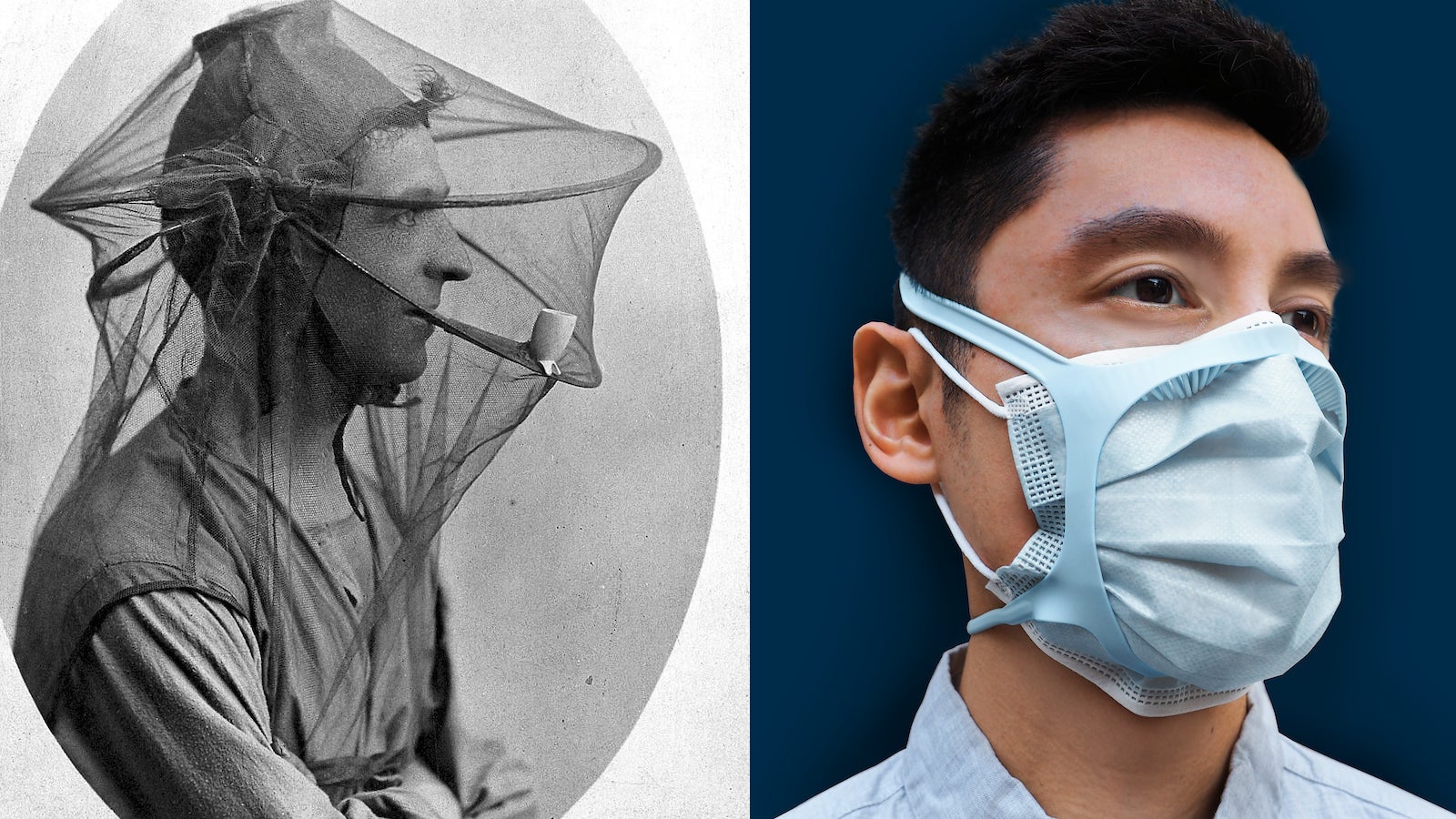

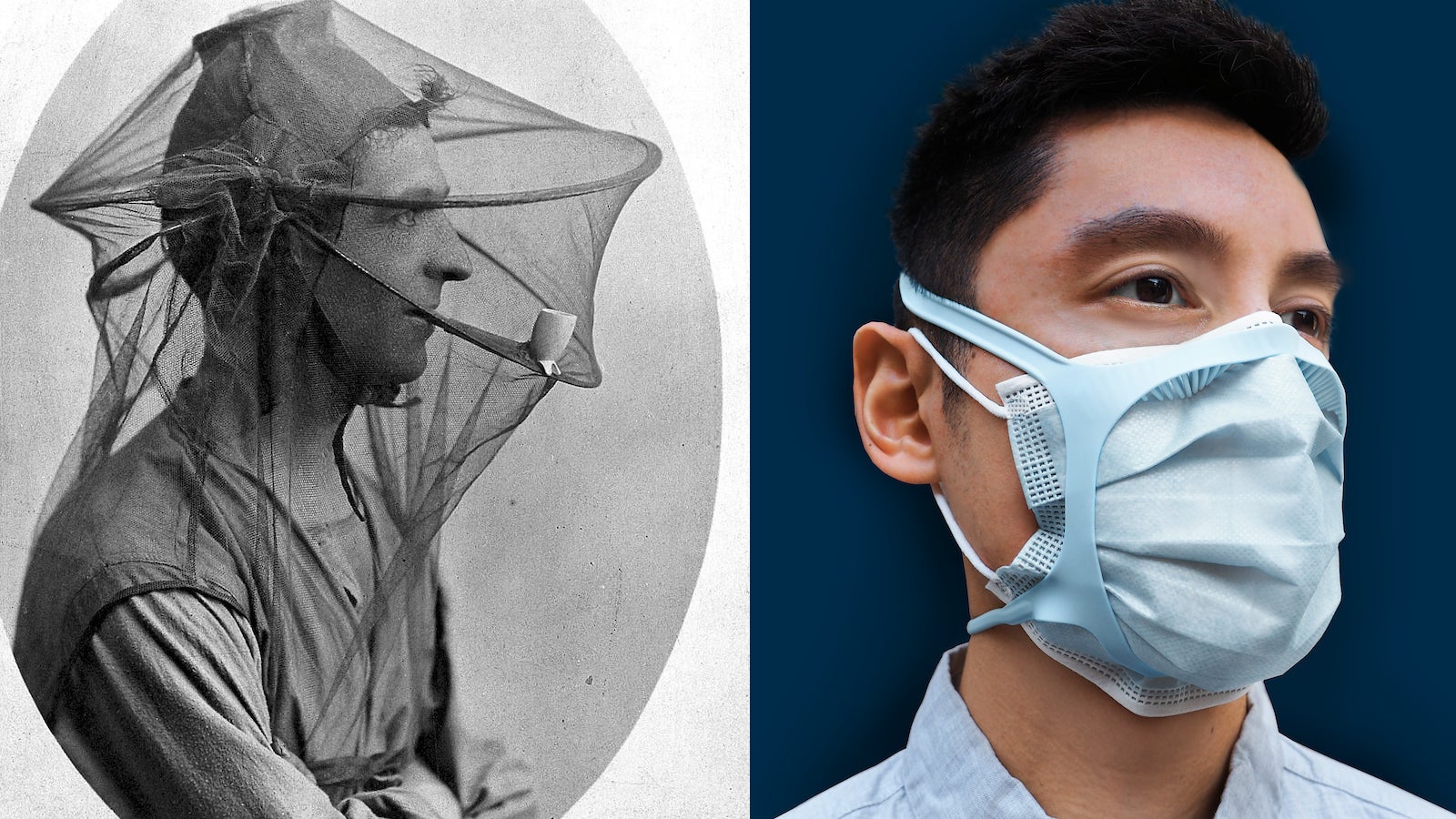

Occupying three rooms at the museum’s first-floor galleries, the exhibition includes about 50 objects and architecture projects, ranging from efficient diagnostic kits to inventive ventilators, homespun face masks, and innovative hospital designs.

Planning for Design and Healing began before the covid-19 pandemic, explains Jeff Mansfield, a principal at MASS Design Group and co-curator of the exhibition. It was meant as a survey of the history of creative breakthroughs that emerged from past epidemics, like Alvar and Aina Aalto’s groundbreaking hospital design during Finland’s tuberculosis crisis in the 1930s, or illuminating data visualizations during London’s 1854 cholera outbreak.

But, as it does, covid altered the museum’s plans. Design and Healing morphed from a historical survey to a showcase of promising solutions for the unfolding and still-evolving global health crisis. “One thing that the exhibit tries to reflect is the idea that we’re in the midst of a huge design charette,” explains Mansfield, referring to focused problem-solving sessions traditionally convened by architects. “We need to be all hands on deck—scientists, designers, anyone who wants to come to the table—to figure out how we can make this planet safer and healthier.”

Ellen Lupton, Cooper-Hewitt’s senior curator of contemporary design, who worked closely with Mansfield and the team at Mass Design on Design and Healing, says they “wanted to include products that have a brilliant idea behind them even if they haven’t been widely-used yet.”

The show also celebrates designers’ instinct to forgo intellectual property rights in times of crisis. “Designers are making use of GitHub and other platforms to share plans to just get it out there,” Lupton explains. The Italian engineers who figured out how to turn a snorkeling mask into a breathing respirator, for example, have open-soured the 3D printed valve for anyone to adopt.

Designing for the mental and emotional toll of the pandemic

MASS principal Jeff Mansfield, an architect who specializes in designing spaces for deaf populations, says that working on the exhibition during the pandemic has also exposed underserved populations. “The western vision of healthcare is privileged,” he says. “But now we see a wide and diverse multitude of experiences.” The erosion of the so-called “ideal user” taught in human factors courses is best exemplified by the array of face coverings included in the exhibition. There’s a face mask for women who wear the hijab, a solution for turban-wearing Sikhs, a clear mask for deaf and hard of hearing populations, and an origami-inspired mask meant to fit different face shapes. “It really shows the plurality of our society,” he says.

Beyond physical solutions, Design and Healing also underscores how designers have been attuned to the mental and emotional wallop of the pandemic. Included in the show are objects like a poster addressing the Sinophobia that flared up during covid-19, Naomi Osaka’s cotton face mask bearing Breonna Taylor’s name, and a hospital in Haiti that features tranquil courtyards for recuperating tuberculosis patients. Curators also commissioned Seattle-based multimedia artist Samuel Stubblefield to compose a soothing melody to play through the galleries. The glass and metal solarium at the Cooper Hewitt mansion (once the home of tycoon Andrew Carnegie) has been recast as a healing room decorated by colorful cushions hand-sewn by New Delhi-based designers Sahil Bagga and Sarthak Sengupta.

“Oftentimes we operate under a survival mindset when we’re facing with a crisis,” says Mansfield. “But one of the things we highlight in the exhibit is the idea that craft and beauty are as important in times of insecurity.” Good design, he explains, can offer a sense of dignity, comfort, and resilience for people under great stress.

Designing for ever-present epidemics

Given the chance to curate another exhibition around the pandemic, Mansfield says he’d like to highlight design solutions meant for entire communities, like family health centers and rural community centers. “If we were to take on a version 2.0 of the exhibit, we’ll be addressing the fact that the pandemic affects us on a personal scale all the way to a systems scale,” he explains.

“Epidemics are probably a new norm,” Mansfield says. “The question is how we build systems that promote community partnership.”