What “Don’t Look Up” gets right—and wrong—about climate change

Climate change is sometimes described as a slow-motion catastrophe, one that often fails to garner enough public concern because it feels vague and intangible, a problem for far in the future. That perception can change quickly, of course, once it’s your house that burns down or gets washed away. But if climate change were plainly visible, and literally hurtling toward the planet, could society rise to the challenge? Leonardo DiCaprio doesn’t seem to think so.

Climate change is sometimes described as a slow-motion catastrophe, one that often fails to garner enough public concern because it feels vague and intangible, a problem for far in the future. That perception can change quickly, of course, once it’s your house that burns down or gets washed away. But if climate change were plainly visible, and literally hurtling toward the planet, could society rise to the challenge? Leonardo DiCaprio doesn’t seem to think so.

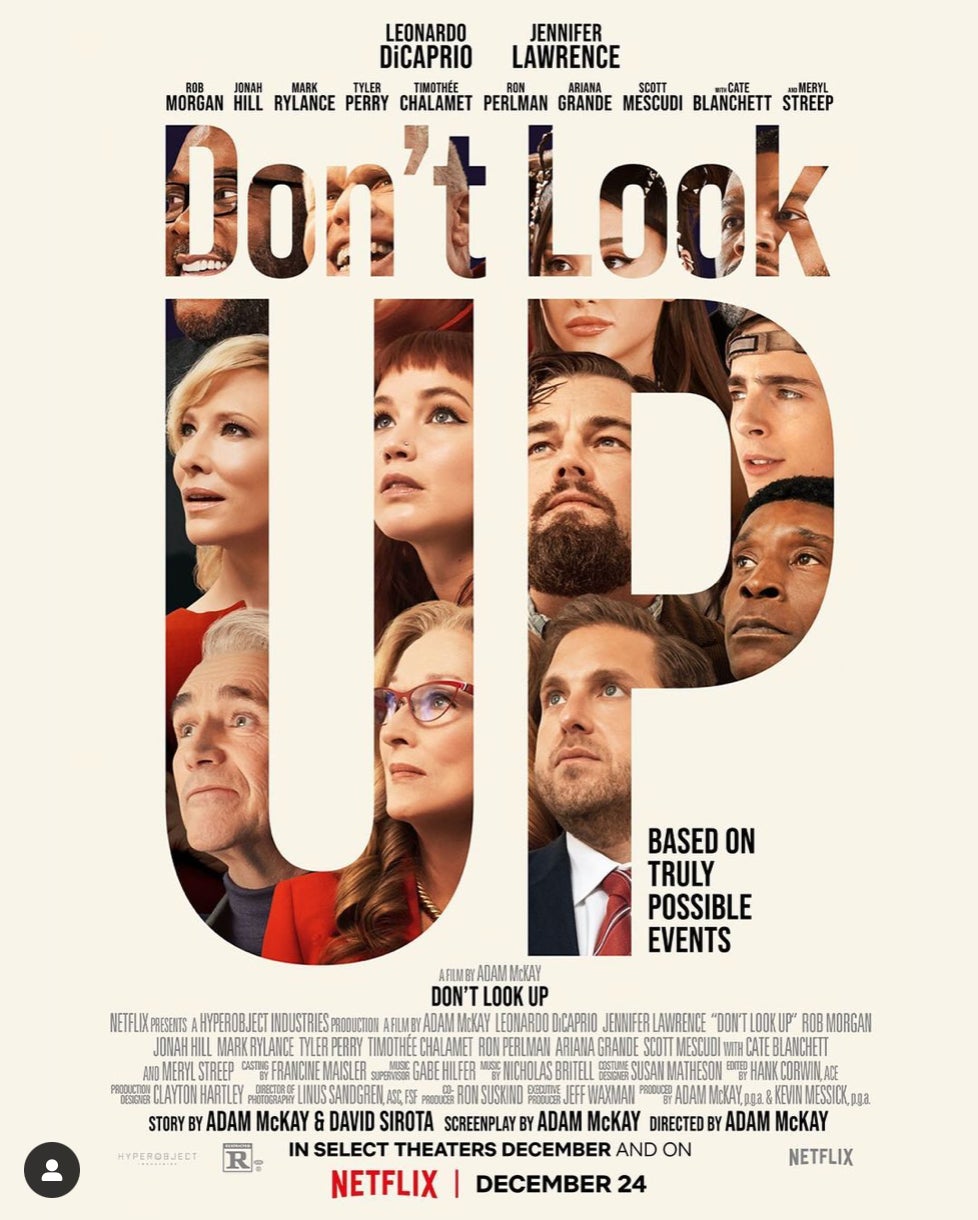

That’s the premise of Don’t Look Up, the latest film from writer/director Adam McKay, who has used snarky wit to unravel other knotty socio-political issues in movies like Vice, about Dick Cheney, and The Big Short, about the financial crisis. Ostensibly a comedy (although viewers should expect more exasperated sighs than laughs), the movie stars DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence as anxiety-riddled astronomers who stumble on a giant “planet-killer” comet making a bee-line for Earth. It’s essentially a reboot of the 1998 Bruce Willis masterpiece “Armageddon,” except no one can agree on what to do about the comet—or whether it even exists. No more spoilers, I promise, but let’s just say it’s not a typical feel-good holiday flick.

DiCaprio has long been an outspoken advocate for action on climate change, and as his character screams about data and pounds the table on network news talk shows, stupefied that no one grasps the gravity of the problem, Leo doesn’t seem to be acting as much as leveraging his stardom to plead directly with his audience. It’s easy to be cynical about celebrity activists, but DiCaprio is one of the only people on Earth who could turn a diatribe about climate change into the number-one streaming movie globally.

From an awareness-raising perspective, Don’t Look Up is clearly a success. And it gets a few key points right about the climate crisis. But the limitations of Hollywood screenwriting and the choice of a comet as a metaphor tend to obfuscate the true nature of the problem. Here’s what Don’t Look Up gets right, and wrong, about climate change.

Right: The science is screaming in our faces

In one scene, DiCaprio’s scientist quibbles with Meryl Streep, playing a Trump-esque US president, about whether or not the comet is 100% certain to hit the earth. The debate recalls that over the scientific consensus on climate change, which is now over 99% in support of the hypothesis that human-produced greenhouse gases are dangerously warming the planet. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report released in August was unequivocal on that point, with 4,000 pages of evidence to back it up. Yet, as sociological research has shown, scientific facts don’t tend to be very effective in changing the minds of climate (or, apparently, comet) skeptics.

Right: Critical minerals are the next gold rush

Mark Rylance has a delightfully creepy turn as a Musk/Jobs/Zuckerberg-esque eccentric tech billionaire, who discovers that the comet is rich in rare earths and other critical minerals for electronics, batteries, and clean energy hardware. This twist is spot-on: Demand for these minerals, which are essential for the tech needed to replace fossil fuels, is exploding, and a gold-rush mentality has gripped mining investors in China, central Africa, South America, and other regions where these minerals are present. It’s very likely that trillion-dollar fortunes will soon be made in critical mineral mining, in spite of the ubiquity of labor and environmental concerns at such mines. The movie captures that paradox: That the solution to the climate crisis carries a high risk of instigating other forms of environmental catastrophe.

Wrong: Technology alone will fix the problem

On Twitter on Dec. 28, McKay noted correctly that most of the technology we need to slow climate change already exists. Blowing up a comet, by contrast, requires a lot of novel innovation. But the deeper flaw in the comet metaphor is that technology, existing or not, is only part of what’s needed to address climate change. The earth system is already permanently altered, and there will never be a button someone can push that will “fix” climate change and return nature to a pre-warming state. Climate change will require communities and corporations to adapt to new environmental conditions and constraints on natural resources, and to re-evaluate their economic and political norms and values, for generations to come. The complexity of that collective action challenge goes a long way to explaining why progress on climate is so slow. If it really was as straightforward as blowing up a comet, it would be done already.

Wrong: The US can/will solve the problem by itself

One of the movie’s stranger plot choices is that geopolitics are almost totally absent. We see flashes of global news audiences following updates about the comet, but until the very end it is framed as the exclusive purview of the White House. Climate change clearly requires more global buy-in; again, it can only be addressed through collective action. The comet metaphor also dodges the question of responsibility, of who caused the crisis (God, maybe, according to Timothée Chalamet’s character in the movie; US and European fossil fuel companies, mainly, in the case of climate change), and how the collective response should be shared.

Still, the comet metaphor may be useful as a thought experiment for considering the ethical implications of geoengineering: In the face of catastrophe, does one country have the right to do something that could affect the globe, like spraying aerosols into the atmosphere? Kim Stanley Robinson’s recent sci-fi novel The Ministry for the Future also tackles this question.

By the end, there’s one point Don’t Look Up nails that applies equally to climate change and the pandemic: In a time of crisis, sometimes the best thing you can do is turn off your phone and enjoy a glass of wine and a good meal with your friends and family.

🎧 For more intel on popular movies, listen to the Quartz Obsession podcast episode on sequels. Or subscribe via: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher.