Seven of the world’s most unusual bus stops are in this small Austrian town

In most cities, the bus stop is the lowliest piece of urban infrastructure. Not so in Krumbach, a small, rural town in a region of Austria known as Bucklige Welt (“hunchbacked world”) because of its hilly landscape. Last year, the town’s cultural association invited seven architects from Chile, Russia, China, Norway, Spain, Belgium, and Japan to design bus shelters for its 1,000 residents. Instead of their typical fees, the architects were offered vacations in Krumbach. (The Schloss Krumbach, an 11th-century castle converted into a hotel, is a popular local attraction; it offers a wellness spa, as well as tours of its former dungeons.) The bus stops opened this month, accompanied by an exhibition at the Vorarlberg Architecture Institute.

In most cities, the bus stop is the lowliest piece of urban infrastructure. Not so in Krumbach, a small, rural town in a region of Austria known as Bucklige Welt (“hunchbacked world”) because of its hilly landscape. Last year, the town’s cultural association invited seven architects from Chile, Russia, China, Norway, Spain, Belgium, and Japan to design bus shelters for its 1,000 residents. Instead of their typical fees, the architects were offered vacations in Krumbach. (The Schloss Krumbach, an 11th-century castle converted into a hotel, is a popular local attraction; it offers a wellness spa, as well as tours of its former dungeons.) The bus stops opened this month, accompanied by an exhibition at the Vorarlberg Architecture Institute.

The funds for the project were mostly raised privately, which perhaps doesn’t make it the best model for (non-libertarian) city planners. But it does put the bus stops squarely in the tradition of follies, structures that split the difference between architecture and sculpture.

A popular feature of 18th- and 19th-century garden architecture, follies are primarily meant as ornament, or at least subordinate their practical purposes to the novelty of their form. Follies were given new life in the 20th century by self-reflexive architects like Philip Johnson (who planted them around his New Canaan estate like garden gnomes) and Zaha Hadid (whose acclaimed fire station in Weil am Rheim, Germany, was only ever briefly in use). Follies allowed avant-garde architects to build when clients weren’t forthcoming or the political climate wasn’t favorable. The Russian architect Alexander Brodsky, whose Krumbach bus shelter is at the top of this story, was limited in his early career to designing installations and even 2-D buildings; he was a leading figure of the so-called “paper architecture” movement.

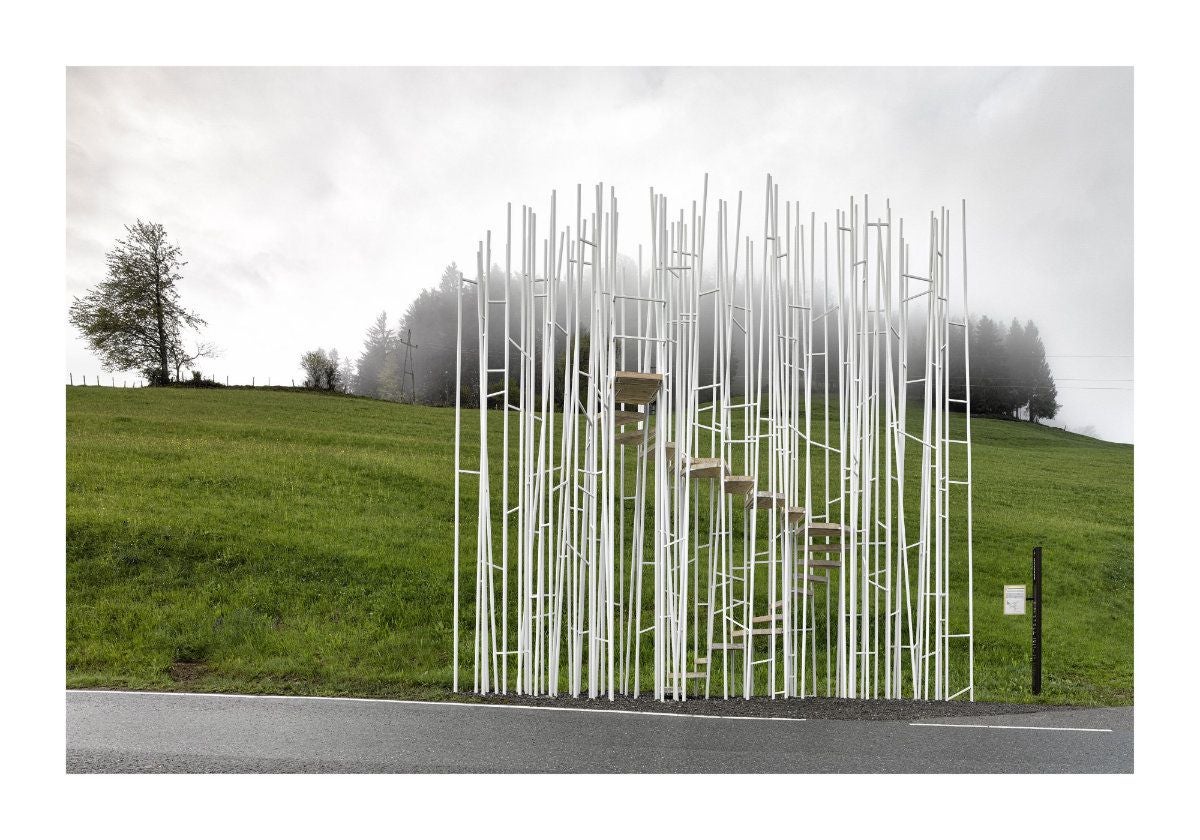

The Krumbach bus stops are all the more winking because their conceptual flights of fancy are firmly grounded in quotidian purpose. Except perhaps for Sou Fujimoto’s open, grove-like structure (below), which doesn’t offer much in the way of shelter at all. But at least the bus won’t miss it.

Scroll down for the rest of the designs and statements about them from their architects. Sou Fujimoto, Japan: “Everyone may climb the tower-like bus stop to enjoy panoramic views of Krumbach. A transparent forest of columns can create interesting scenery in a site surrounded by nature.” (Photo: Adolf Bereuter/BUS:STOP Krumbach)

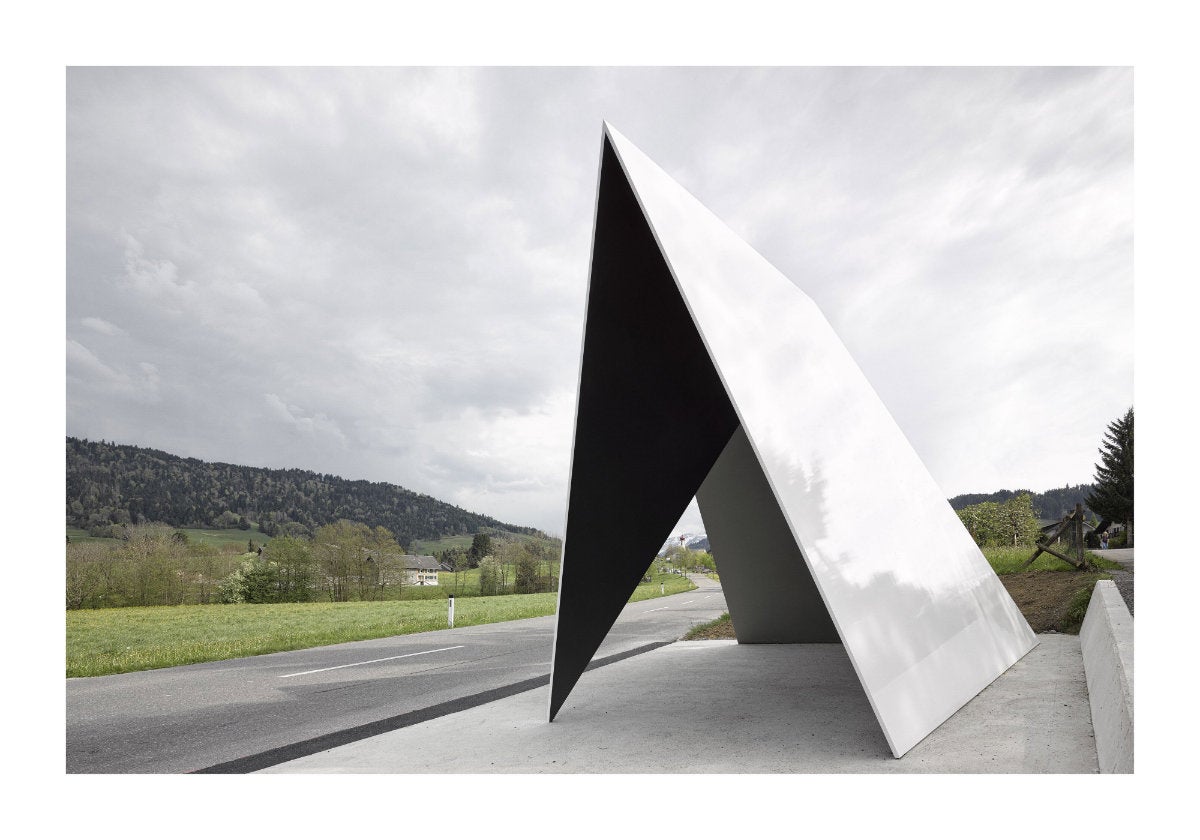

Smiljan Radic, Chile: “Urban exteriors seem to be the natural extension of small, protected interior spaces. Zwing BUS:STOP seeks to express this domesticity.” (Photo: Adolf Bereuter/BUS:STOP Krumbach)

Ensamble Studio, Spain: “Ensamble Studio’s BUS:STOP for Krumbach explores the appropriation of a local technique used to stack wood planks in the drying barns in the region.” (Photo: Adolf Bereuter/BUS:STOP Krumbach)

Architekten de Vylder Vinck Taillieu, Belgium: “How it is possible that a simple idea of a roof originates from a constantly re-occurring vision of a Sol LeWitt drawing…” (Photo: Adolf Bereuter/BUS:STOP Krumbach)

RintalaEggertsson Architects, Norway: “The structure becomes the sum of these viewing activities, a gathering and organization of paths of attention.” (Photo: Adolf Bereuter/BUS:STOP Krumbach)

Amateur Architecture Studio, China: “It is like a 120 SLR folding camera that people can sit in.” (Photo: Adolf Bereuter/BUS:STOP Krumbach)