Alibaba and JD.com are battling for a huge emerging market: poorer, inland China

China’s two biggest e-retailers—Alibaba and JD.com—have built multi-billion-dollar businesses on the online shopping craze that’s swept China’s big cities in the last decade. Both companies are raising capital: JD.com debuts today on the Nasdaq, and Alibaba, the top dog, will IPO in New York sometime this summer.

China’s two biggest e-retailers—Alibaba and JD.com—have built multi-billion-dollar businesses on the online shopping craze that’s swept China’s big cities in the last decade. Both companies are raising capital: JD.com debuts today on the Nasdaq, and Alibaba, the top dog, will IPO in New York sometime this summer.

They’re going to need it. The Chinese e-commerce markets with the most promising growth are the ones outside of those wealthy but saturated metropolises where both companies now operate with ease. But what separates the rich coastal cities from fast-growing hinterland markets is a thicket of inefficiency. As Alibaba’s and JD.com’s prospectuses reveal, penetrating that thicket while maintaining quality control and speedy service is going to be incredibly expensive.

Converging models

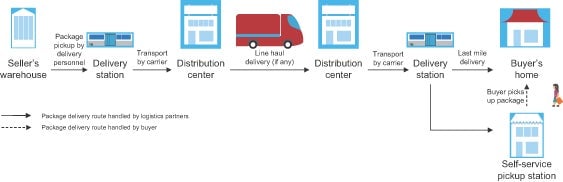

First, though, a review of the two companies’ differences: Alibaba makes most of its profit from its online marketplaces, where it charges third parties for advertising and, in some cases, pockets commissions on sales (not unlike eBay). JD.com delivers electronics and other goods from its warehouses directly to consumers (like parts of Amazon).

But their models are growing more similar. In 2013, Alibaba began rapidly building out a joint-venture logistics network (paywall). JD.com, meanwhile, now has 29,000 third-party sellers on its online marketplace, some of which use its existing delivery infrastructure. Most of the capital JD.com raised last night will go toward expanding that infrastructure even more.

Why the shared emphasis on “logistics”?

The ability to guarantee speed and reliability will win market share in China. But that’s easier said than done. Consumer complaints about online retail services already number the hundreds of millions, and are rising fast. Inefficiencies are a particularly big problem during peak shopping periods like Singles Day, Nov. 11. That day last year, Alibaba users bought 35 billion yuan ($5.8 billion) worth of goods, while JD.com made sales of 10 billion. Combined, that’s nearly five times the sales volume of the US’s Cyber Monday, when shoppers are offered online deals in advance of the winter holiday season. But that massive volume overwhelms China’s domestic express delivery industry, which can handle only about half the orders placed on and just before Nov. 11, causing rampant delays—and prompting Jack Ma, Alibaba’s founder, to identify logistics as something he was “most concerned about.”

And while the record-breaking sales numbers of Singles Day might be good press for the online retail platforms, it’s less rosy for the express delivery companies that partner with them. Because the e-commerce companies control pricing, they’re stuck eating the costs of extra staffing, says Xu Yong of China Express Consulting.

Big growth beyond the coast

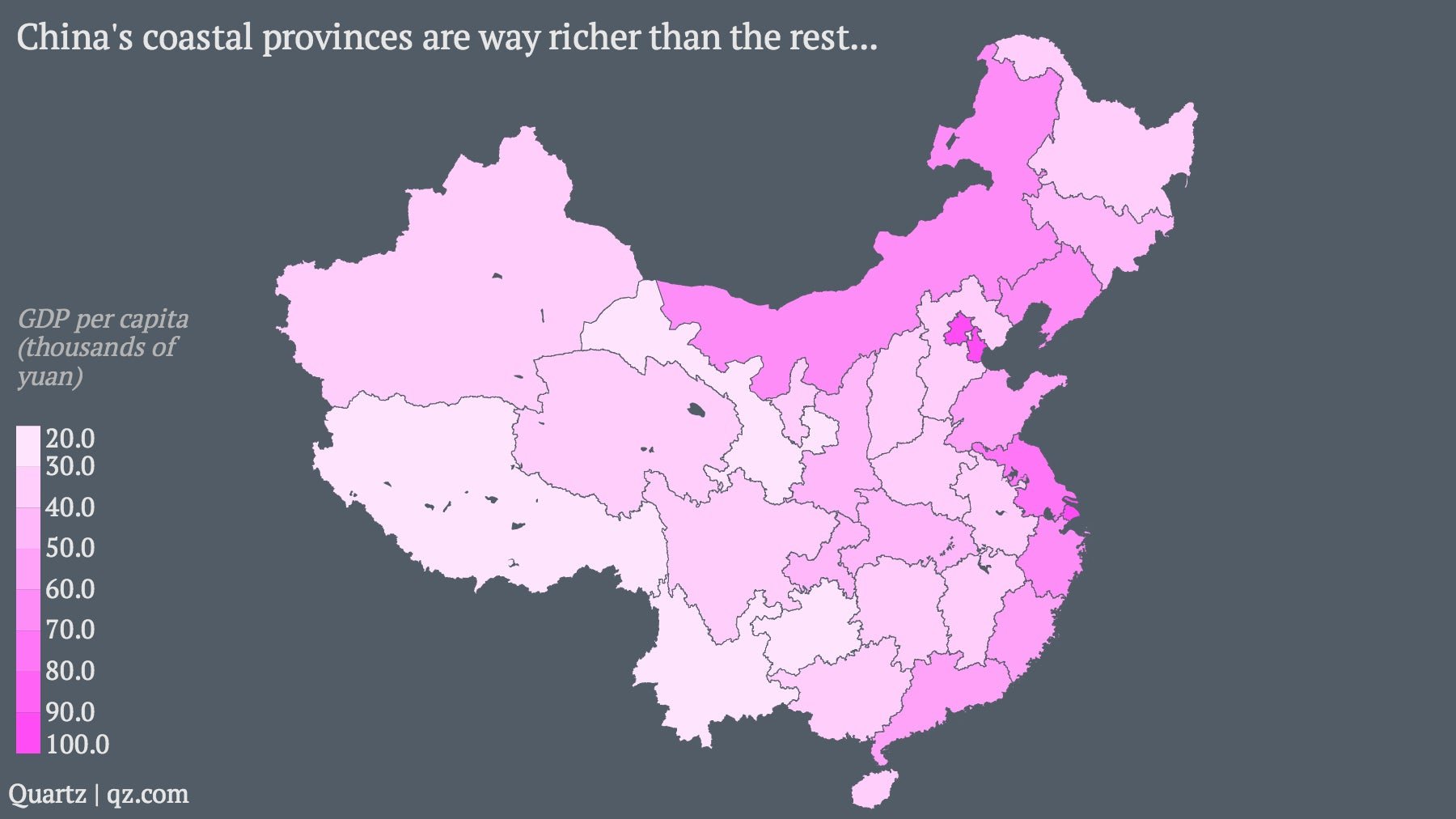

These problems will only intensify as online shopping habits spread beyond China’s urban hubs and into the harder-to-reach provinces. But that’s where the big opportunities lie. While the biggest volume of online retail sales comes from the early-adopting coastal provinces such as Guangdong, Jiangsu and Zhejiang, according to iResearch, the sector’s growth is fastest in smaller inland provinces. The top three are Ningxia, Qinghai and Guizhou, where disposable incomes are surging.

Though GDP per capita doesn’t necessarily reflect average disposable income, this map should still give you a sense of how much room there is to grow beyond the richer coastal provinces:

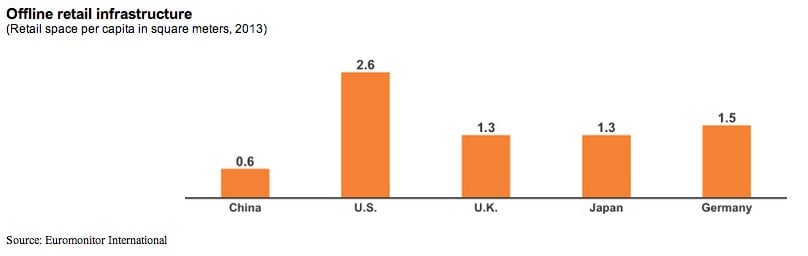

And we’re not talking about thinly populated farmland here. Outside the 35 biggest cities—megalopolises like Shanghai and provincial capitals like Chengdu—there are still 125 other cities whose populations exceed one million residents, and many hundreds more with populations of more than 500,000. Brick-and-mortar shopping options there are much scarcer than in the coastal major cities, limiting the quality, safety and selection of available products, says Alibaba’s prospectus (p.130).

Lots of red tape

But freight infrastructure and well-trained personnel in these promising new inland markets are also much scarcer. Logistics networks are fragmented and unreliable, smothered by thick layers of bureaucracy. Parcel delivery services must obtain courier permits from postal bureaus in each province, says JD.com’s prospectus, as well as separate permits for cross-province delivery. They must also earn road freight permits from each provincial-level transport ministry.

Into China’s big backyard

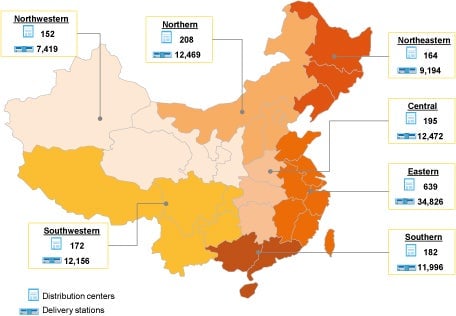

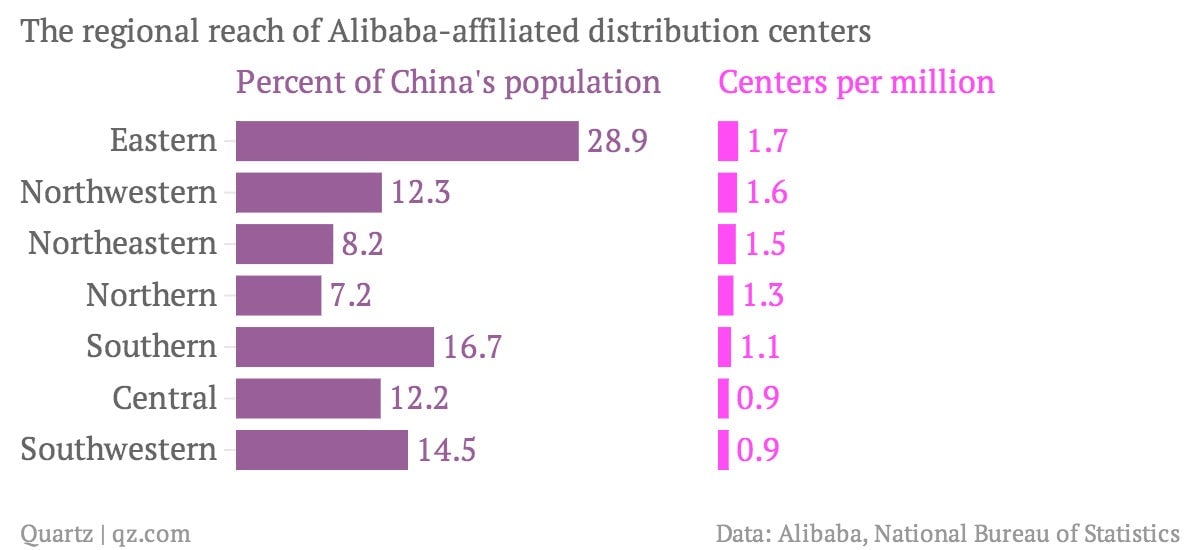

The fact that Alibaba’s network is run through 14 “strategic delivery partners”—Alibaba doesn’t own the infrastructure—has helped it expand fast, with 1,700-plus delivery centers now operating. Last year, the network delivered 5 billion parcels in more than 600 cities:

But as you can see, beyond the wealthy coastal corridor, Alibaba’s presence is thinner on the ground:

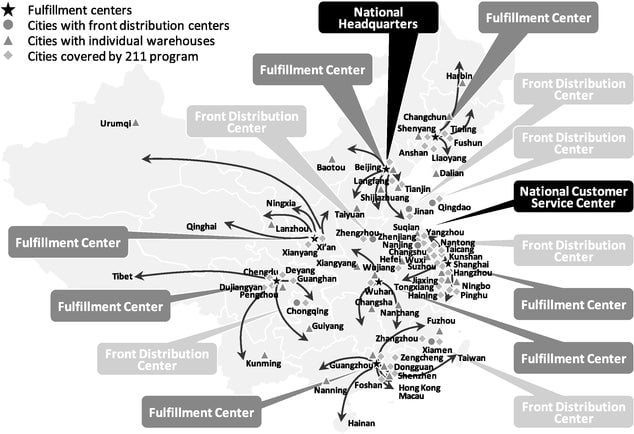

Though JD.com has been building its logistics empire for more than half a decade, it has fewer delivery centers than Alibaba—1,620 in 36 cities. But it actually operates these, which allows it to promise same-day delivery in 43 cities and next-day delivery in a whopping 256. Delivery time averaged three days on Alibaba’s network.

Expensive expansion

Whether Alibaba’s lean approach to logistics will prevent it from turning orders around as fast as its competitor remains to be seen. But JD.com’s experience makes it clear why Alibaba selected the cheaper route: JD.com’s logistics buildout has been remarkably expensive.

How expensive? As Huxiu, a Chinese tech magazine, notes in this must-read analysis of JD.com’s prospectus (link in Chinese), though it’s attracted $1.8 billion in financing in the last few years alone, the company reports 3.6 billion yuan ($583 million) in fixed assets, including 599 million yuan in land use rights, 1.3 billion yuan worth of construction in progress and 1 billion yuan in property. For reasons that are unclear, this buildout has also been messy: JD.com’s prospectus says 18% of the warehouses and 39% of the delivery stations it leases have never verified that they actually own the property.

And geographically speaking, it has a ways still to go. For instance, its fulfillment center in Xi’an currently serves Qinghai, Xinjiang and Ningxia. That implies JD.com’s couriers must travel 547 miles (880 kilometers) to reach Xining, Qinghai’s capital. Deliveries bound for Urumqi face a 1,585-mile journey:

The spending race ahead

That’s probably why JD.com plans to spend up to $1.2 billion of its new capital on building its delivery infrastructure further into China’s backcountry—a plan that could mean it takes years before the company turns a profit. Investors don’t seem too worried; JD.com just raised $1.78 billion.

Investors will probably feel even more confident in China’s online retail outlook when Alibaba lists publicly (it filed initial paperwork with the US securities regulator on May 7). JD.com’s heady valuation suggests that Alibaba, which has long been profitable, will be worth even more than many imagined—perhaps as high as $200 billion (more than Facebook). What they might not realize is that the business models that they’re banking were built for the swath of China that’s now essentially a middle-income country. Whether those models will work as smoothly and cheaply in the emerging market that is the rest of China is an open question.