So much for being “bossy”—women are called “pushy” twice as much as men

During her three-year tenure, former New York Times executive editor Jill Abramson was described (anonymously, of course), as many things, including “brusque,” “condescending,” and of course, “very, very unpopular.”

During her three-year tenure, former New York Times executive editor Jill Abramson was described (anonymously, of course), as many things, including “brusque,” “condescending,” and of course, “very, very unpopular.”

But none of these attributes seemed to sting women as a whole quite like the one used by another anonymous staffer in an interview with the New Yorker’s Ken Auletta.

After Abramson was fired last week, Auletta wrote that Abramson had long believed she was being paid less than her male predecessor, Bill Keller, and that she had both asked for a raise and hired a lawyer to look into the disparity:

“She confronted the top brass,” one close associate said, and this may have fed into the management’s narrative that she was “pushy,” a characterization that, for many, has an inescapably gendered aspect.

In the ensuing media storm, writers (including me) seized on the word “pushy,” arguing that it’s unlikely a man would have been thus described for his aggressive tendencies.

Others even took it up as a badge of honor:

“One day, we’ll be grateful to Jill Abramson for being so pushy,” wrote Jill Morgenthaler in Quartz. Re/Code editor Kara Swisher wrote a faux letter “From One Pushy Media Dame to Another.”

Of course, it’s possible to be “pushy” and a bad manager, and it’s conceivable that Abramson was a terrible one. In an interview with Vanity Fair, Timespublisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr. said several newsroom staffers had complained that Abramson alienated her colleagues and made unilateral decisions.

But there’s still the question of whether a male editor’s Abramson-style imperiousness or outbursts would have been similarly frowned upon—or even if they would have registered. In other words, what do we call it when a man is “pushy?”

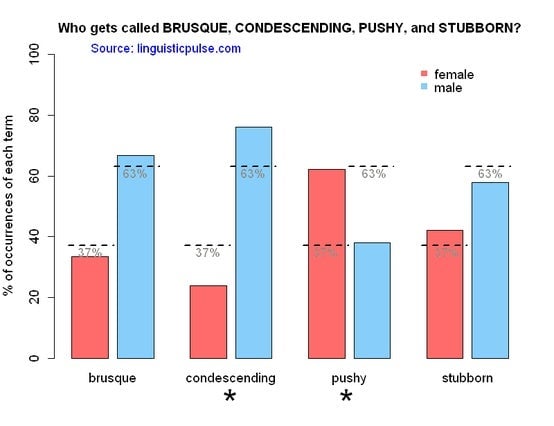

Georgia State University linguistics PhD student Nic Subtirelu, who runs the Linguistic Pulse site, gathered a random sample of 200 to 300 occurrences of each of the above adjectives from the Corpus of Contemporary American English, a repository of 450 million words from fiction and nonfiction texts published between 1990 and 2012. He isolated the adjectives that were used to describe a person or their personality, and he discarded the instances that referred to something other than the subject (e.g. “Her parents were extremely pushy.”) He was left with about 120 uses of each term, each pulled randomly from the modern American zeitgeist.

Women are only mentioned about 37% of the time in the Corpus, so to determine whether writers use a certain adjective to describe them disproportionately, Subtirelu had to see whether it was used significantly more than 37% of the time.

“Brusque” and “stubborn” were equal-opportunity, he found:

I did not find that brusque or stubborn were used in a gendered manner, at least not to a significant degree … These two words were used for men and women at about the rate we might expect.

That was not the case, however, for “pushy,” which was aimed at women far more frequently than men:

Women are labelled pushy about twice as frequently as men in COCA even though men are mentioned nearly twice as frequently as women.

Men, meanwhile, were far more likely to be labeled “condescending.”

Subtirelu argues that this doesn’t mean some sort of perverse gender balance has been struck, with women considered overly pushy and men overly condescending:

Condescending seems to differ from pushy and bossy in an important way, namely that it seems to acknowledge the target’s authority and power even if it does not fully accept it.

That is to say, “condescending” implies someone is abusing power they already have. “Pushy” suggests an improper attempt to charge through a barrier.

In the aftermath of the “Ban Bossy” campaign, Subtirelu ran the same analysis with “bossy” and found a similar phenomenon—it was used for women and girls about one and a half times more than for men and boys.

To Subtirelu’s smart analysis, I would only add that these trends are about more than just observed behavior, or even pervasive sexism—they’re about expectation. People, including people like Sulzberger and Abramson’s newsroom colleagues, expect women to be communal leaders and men to be autocratic ones. When women violate those norms—or “push” past them, if you will—they still suffer consequences.

This post originally appeared at The Atlantic. More from our sister site: