How to make electric cars sexy: Race them on the streets of the world’s biggest cities

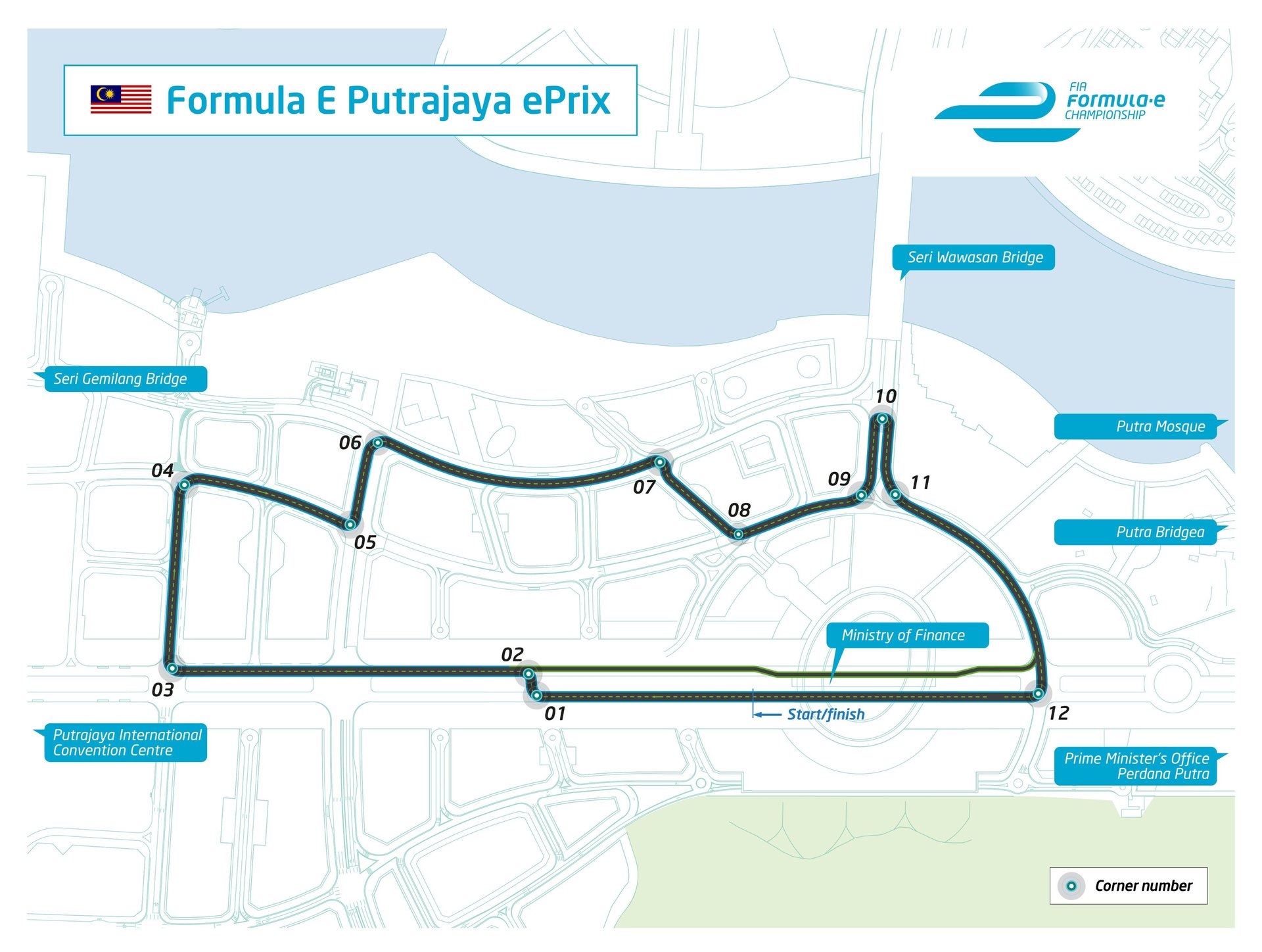

The streets of London are not made for speed. Indeed, they are barely made for cars. Yet on June 27 next year, the British capital will host the closing fixture of Formula E, a motor-racing championship unlike any other: The vehicles zipping through London’s ancient streets will all be electric. And they will have got there after racing the streets of Beijing, Buenos Aires, Berlin, Miami, and five other world cities. The first test runs (on a more conventional racing circuit, Donington Park) start in Britain next month.

The streets of London are not made for speed. Indeed, they are barely made for cars. Yet on June 27 next year, the British capital will host the closing fixture of Formula E, a motor-racing championship unlike any other: The vehicles zipping through London’s ancient streets will all be electric. And they will have got there after racing the streets of Beijing, Buenos Aires, Berlin, Miami, and five other world cities. The first test runs (on a more conventional racing circuit, Donington Park) start in Britain next month.

Formula E was established after a report commissioned by the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA), the governing body for auto racing, argued that an electric-car championship would meet a business need for electric-car manufacturers looking for a platform. In August 2012, the FIA awarded the contract to run the franchise to Alejandro Agag, a London-based businessman.

Agag, a self-confessed “petrolhead,” is no Elon-Musk-style electric-car evangelist; we talk in the back of his black Mercedes S Class, which manages about 15 miles to the gallon (6.3 km/liter) in the city. But the handsome Spaniard is well-placed to make a success of the championship. A former member of the European Parliament, soccer club chairman, and boss of a GP2 (another motor-racing championship) team, Agag is well connected in European sports. He counts among his friends Formula 1 impresario Bernie Ecclestone, as well as Lakshmi Mittal, the richest man in Britain, with whom he bought the Queens Park Rangers football club. He also brought Formula 1 to Spanish television in 2002, growing its audience from next-to-nothing to 10 million in five years (paywall).

Agag put together the brand-new championship at astonishing speed. Starting Sept. 13 at Beijing’s Olympic stadium, just 25 months after Agag took up the franchise, 20 drivers from 10 teams will race 40 custom-built electric cars around 10 major world cities—rising to 12 cities in 2015 and 14 in 2016.

If it works, the most optimistic projections, according to an Ernst and Young study (pdf)—admittedly, one commissioned by Agag’s company—are that Formula E could help the auto industry sell between 52 million and 77 million additional electric vehicles (EVs) over the next 25 years, generate an extra €142 billion ($193 billion) in worldwide sales, and create 42,000 permanent jobs, thanks to the championship’s ”strategy to encourage technological innovations, social awareness and infrastructure development.”

The skeptical crowd

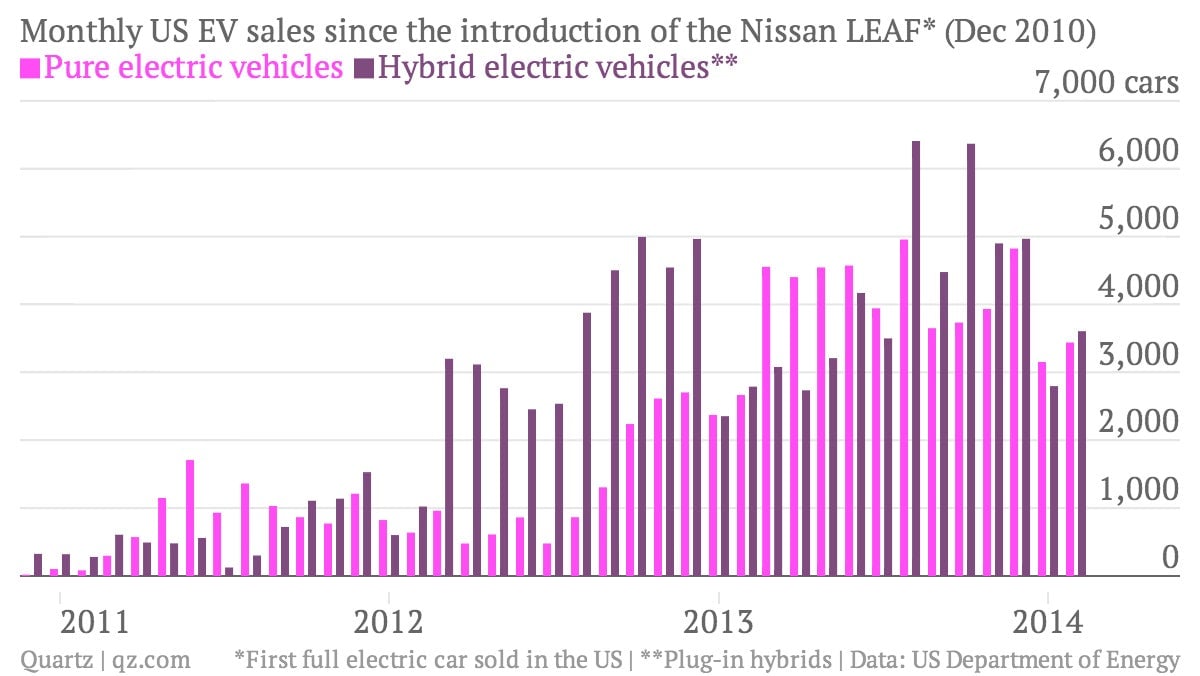

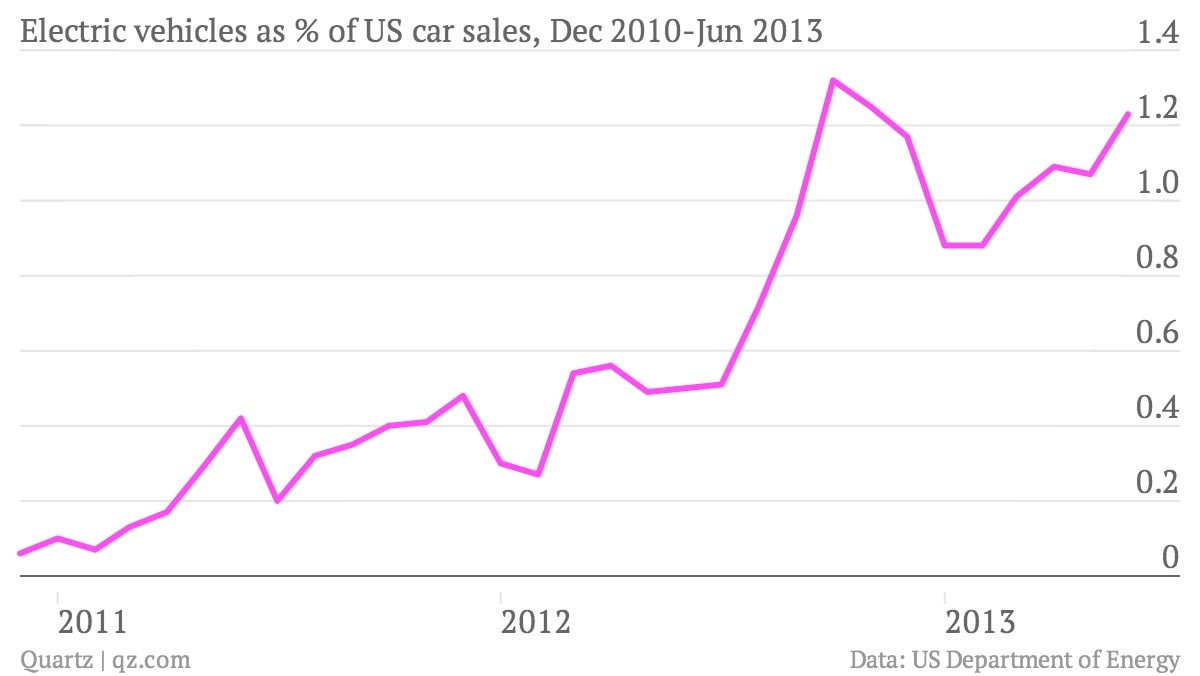

Last year, Americans bought some 48,000 pure electric vehicles. Throw in another 49,000-odd hybrids, like the Toyota Prius Plug-in, and that’s just over 97,000 new cars that can take power from a wall outlet. That’s a healthy jump from the roughly 53,000 sold in 2012. But it’s still a rounding error in the 15.5 million automobiles (pdf, p.8) sold in America in 2013.

The picture in the rest of the world is no rosier: Even including cars that can’t be plugged into a charger but generate electrical power from braking (such as the original Prius), EVs accounted for just over 200,000 (pdf) of the global tally of nearly 83 million cars sold in 2013. That’s 0.24%.

The oft-cited shortcoming of electric cars is that they don’t go far on a single charge—typically less than 100 miles (160km). They also tend to be expensive to buy, even if cheaper to run. And then there are “few public charging stations, expensive residential fast-charging equipment and the fear of new technology,” reports (pdf) the US National Automobile Dealers Association.

But an even bigger hurdle to adoption is that, with the notable exception of the Tesla (which was asked to participate in Formula E but declined), electric cars inspire no passion. No one dreams of hitting the road in a Nissan Leaf. The BMW i3 inspires no odes. No great novels start in a narcotic haze (pdf) in the back of a G-wiz. Inasmuch as the internal combustion engine defined the 20th century, the electric vehicle has singularly failed to capture the imagination of the 21st.

Besides pushing technological innovation, then, the goal of Formula E is to make electric cars sexy. Motor racing has been used to get people revved up since the earliest days of the car, says Paul Drayson, who served on the FIA commission that recommended Formula E and owns Drayson Racing, one of the competing teams. He cites the example of the Paris-Rouen race of 1894, which John Heitmann, president of the Society of Automotive Historians and a professor at the University of Dayton calls “among the most important technological demonstrations” in automobiles. ”We think that by seeing these cars racing, that alone will change a lot of perceptions of people,” says Agag.

A combination of convenient new technologies (the cars won’t need to be plugged in, but will stand over an electrically conducting pad for wireless charging), speed (Formula E cars can do 0-60mph in 3 seconds, barely slower than the 2.5 seconds it takes an F1 car) and glamor (the international locations) may convince people that electric cars can be more than glorified golf carts for the supermarket run. “As the old maxim goes: Racing on Sunday sells cars on Monday,” says Heitmann.

Moreover, the technology will likely find its way to consumers too. Heitmann cites fuel injection and supercharging as inventions that originated in racing. Camshafts and valves, which allows internal combustion engines to breathe, came from the Vanderbilt Cup Racing of the early 20th century. But for casual watchers of the sport, says Drayson, “The point is to convince people that electric cars are the future, that the technology is here, that it works, that it’s exciting.”

A very 21st-century sport

The sport certainly sounds futuristic. Agag has been making a big deal about the noise the cars make; he compares it to the pod racers in Star Wars, in an effort to head off criticism from auto enthusiasts that the electric championship lacks the vroom vroom of traditional racing.

Formula E is also both more global and more online than its predecessors. Unlike the teams of Formula 1, which are primarily European, the teams of Formula E were chosen for geographical diversity. Two of the 10 teams come from the United States, one each from China, India and Japan, two from Britain, and the rest from Monaco, France and Germany.

The organizers plan to make heavy use of social media and games. A video game will allow fans to race against the drivers in real time. And a feature called “tweet to boost” will even let them influence the outcome of the race: Each driver has a set number of “power boosts,” which he can use to briefly increase the car’s power output. The driver whose name is tweeted the most will get an extra boost, probably in the very last lap, which in a tight race could make all the difference.

The choice of street—rather than track—races was also part of the plan. Cities are keen to reduce emissions and are happy to promote clean technologies, says Drayson. London, for example, has mandated that all new taxis plying in the center of the city from 2018 must be zero-emission. In the US, governors of eight states are pushing to put 3.3 million zero-emissions vehicles on their roads by 2025. By holding the races on city streets, cities can promote electric vehicles and appeal to the people most likely to use them. (They also stand to boost their local economies by up to $10 million in spending by visitors on race day, according to Ernst & Young.)

The other reason for holding the races in cities is to reach urban 20- and 30-somethings, who are likely to start buying electric cars as they grow older, and who are also a prize audience for advertisers preaching sustainability and innovation. DHL will push its “green logistics.” Qualcomm, which bills itself as “the world leader in next-gen mobile technologies that accelerate wireless life,” will showcase its wireless charging technology.

A new economics of racing

Still, nobody involved in Formula E is in it just for the good of mankind. The numbers need to add up. Though the championship’s name is a deliberate nod to Formula 1, it has only a fraction of the budget. “Our business model is to have 3% of the cost of F1,” says Agag. “And on the other hand to have revenues higher than 3%” of F1’s revenues.

Running a Formula E team will also be cheaper. An F1 team can cost up to £300 million ($500 million) a year to run, says Drayson. By contrast, the operating budget for Formula E teams has been capped at €3.5 million ($4.75 million). That means more teams might even make a profit, in contrast with Formula 1, where only three of the nine teams that revealed their numbers made any money in 2012.

Among the championship’s cost-cutting measures is that all teams must use the same car in the first year, supplied by Agag’s company. (The outcome of the race will depend on the set-up of the car and the skills of the driver.) Another is that telemetry—the harvesting and analysis of reams of data from the car during the race, which in Formula 1 requires large teams of people and fancy equipment—is being kept to a minimum.

And once teams start building their own cars, they must make them available to other teams for no more than €350,000. That may seem like a guaranteed way to lose money, but the intellectual property the car-makers develop in the course of building and refining their cars will be hugely valuable for other applications, reckons Drayson. ”It is a right-size budget,” says Chetan Maini of Mahindra, the Indian team. Maini is the creator of the Mahindra Reva, an Indian-made electric car that sells in Europe as the G-Wiz.

Ready… set… charge!

On paper, it sounds like the perfect sport: an event that promises exposure for worthy new technology, profits for its backers, and a better planet for everybody else. Indeed, it is hard to find someone skeptical about Formula E. Big corporations have signed up to sponsor the event. Leonardo DiCaprio is an investor. Even the notoriously skeptical bunch at Top Gear, a popular television show about cars, seem convinced.

One reason could be that the risks are small. The money involved is not huge; its start-up nature means there isn’t very much glamor; there is little prestige in winning a brand new championship. But if it works, ”there’s inordinate promise for technology transfer to go from racing to production,” says Heitmann, the car historian. That is good reason to hope Formula E succeeds.