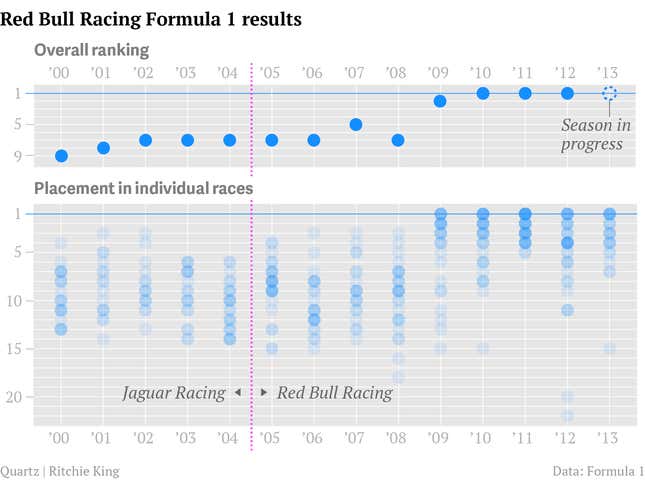

When energy-drink company Red Bull bought Ford’s Formula 1 team Jaguar Racing in 2004, the team was in a shambles. In the five years it was controlled by Ford, its drivers won not a single race. The closest it came to a championship was in 2004 when Jaguar placed seventh in the constructors standings. Out of 11 teams.

Renamed Infiniti Red Bull Racing, the team now dominates Formula 1 racing in much the same way Ferrari did during the glory years of Michael Schumacher in the early 2000s. It has won the double championship—when a team comes first in points both for an individual driver and for the team, or constructor of the car—every year since 2010 and is well on its way to winning its fourth. But advanced engineering accounts only for part of its astonishing success. As important is the way the team uses data.

According to Red Bull’s head of technical partnerships Alan Peasland, some 100 gigabytes of data goes into winning a race. (That’s the equivalent of streaming every episode of the long-running Seinfeld TV series six times over.) A lot of that comes from telemetry, a term that describes data collection on the move. Each car is fitted with around 100 sensors throughout the vehicle. The sensors gather data about temperature, g-forces, spin—and other things—and feed it back to the garage off to the side of the track, where it is analyzed by a team of engineers.

Blazing fast cars… and internet

Data from the race site, wherever it is in the world, also arrives at Red Bull’s UK operations centre in “real time,” something no other team has the ability to do, according to the team’s chief information officer Matt Cadieux. (That also means it is subject to numerous attacks from hackers, though Cadieux says they’re amateurs rather than rival teams.)

The core of Red Bull’s operations is a windowless room in a business park in the English town of Milton Keynes. With space for some 24 analysts sitting in four rows of screens, it has the appearance of a mini-mission control. During every race, experts familiar with different aspects of the car sit here with hefty headphones connected to the drivers, engineers, pit crew, handlers and television sets. In addition to telemetry, they also keep a close eye on the television channels broadcasting the race: Formula 1 regulations don’t allow teams access to other teams’ radio communications or driver cameras but broadcasters have the raw, unedited feed which they often splice into the race.

The other speed

The result is a dramatic increase in the reaction time. In the final race of the 2012 season, Red Bull’s star driver Sebastian Vettel nearly lost the championship after a crash with another car. The team decided against bringing him into the pit to assess the damage. Instead, they kept him on the track while engineers at the off-track garage and in Milton Keynes figured out how bad it was and whether there was a chance of salvaging the race. Vettel went on to finish sixth in the race, enough to win the championship. Peasland attributes that win to his team’s communications.

By contrast, Red Bull lost out in 2009 because of the amount of time it took to identify an illegal maneuver when a rival driver overtook a Red Bull car in the European Grand Prix in Spain. By the time the team put together enough evidence to prove their case—six and a half minutes—their driver had lost so much time and slipped so far back, regulatory action from administrators proved ineffective in helping him regain his position. That wouldn’t happen today; Peasland says data speeds have doubled since 2011, thanks in part to a partnership with AT&T.

As the Formula 1 roadshow descends on South Korea this weekend for 14th race of the season, fans will have their eyes on the track in Yeongam. But a small group of people in Milton Keynes will be just as crucial Red Bull’s success. Increasingly, the speed of the car is not the only speed that matters in Formula 1.