How America fell out of love with writing checks

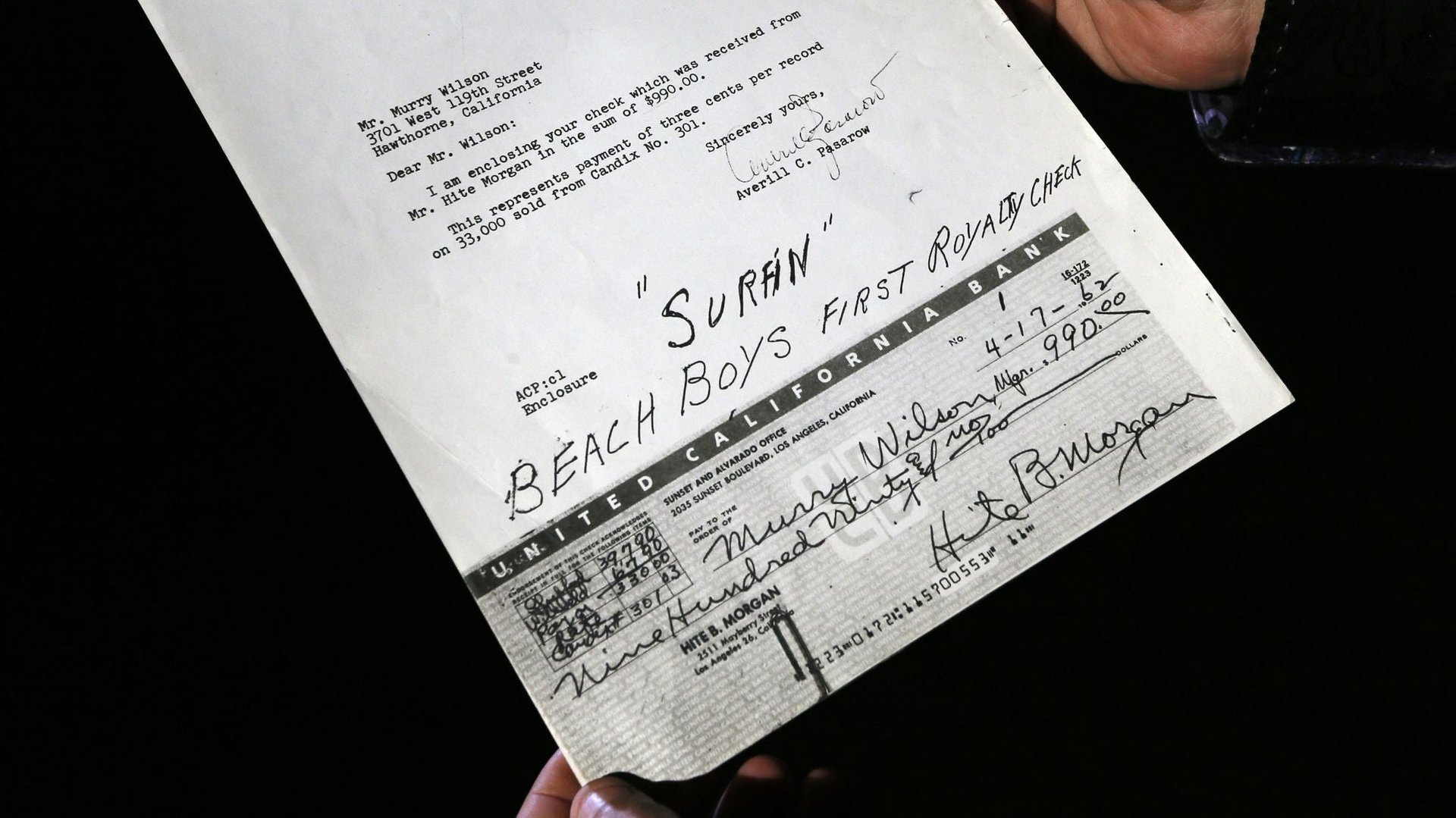

The usage of checks as a payment system has plummeted in the US in recent years. In 2000, checks were used in more than 40 billion transactions, according to a recent report from the Federal Reserve’s Cash Products Office. That number is down to less than 20 billion, according to the Fed’s most recent numbers, which are based on a survey conducted in October 2012.

The usage of checks as a payment system has plummeted in the US in recent years. In 2000, checks were used in more than 40 billion transactions, according to a recent report from the Federal Reserve’s Cash Products Office. That number is down to less than 20 billion, according to the Fed’s most recent numbers, which are based on a survey conducted in October 2012.

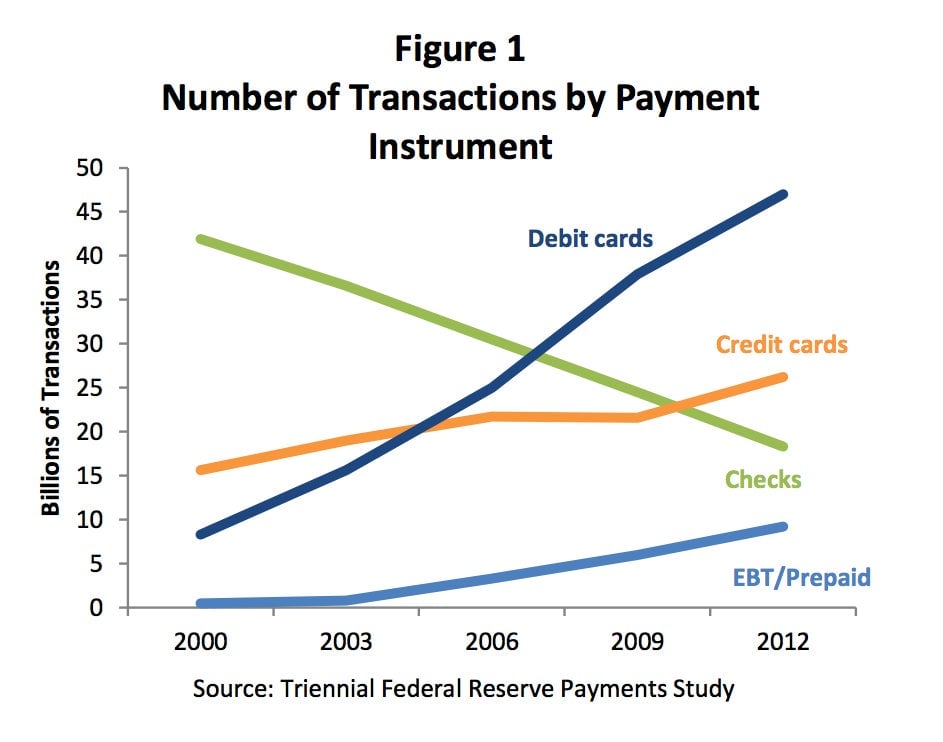

When it comes to American payment preferences, checks run a distant fourth. (At least when you measure the overall number of transactions. Checks are used for about 19% of the value of all purchases, slightly higher than debit or credit cards.)

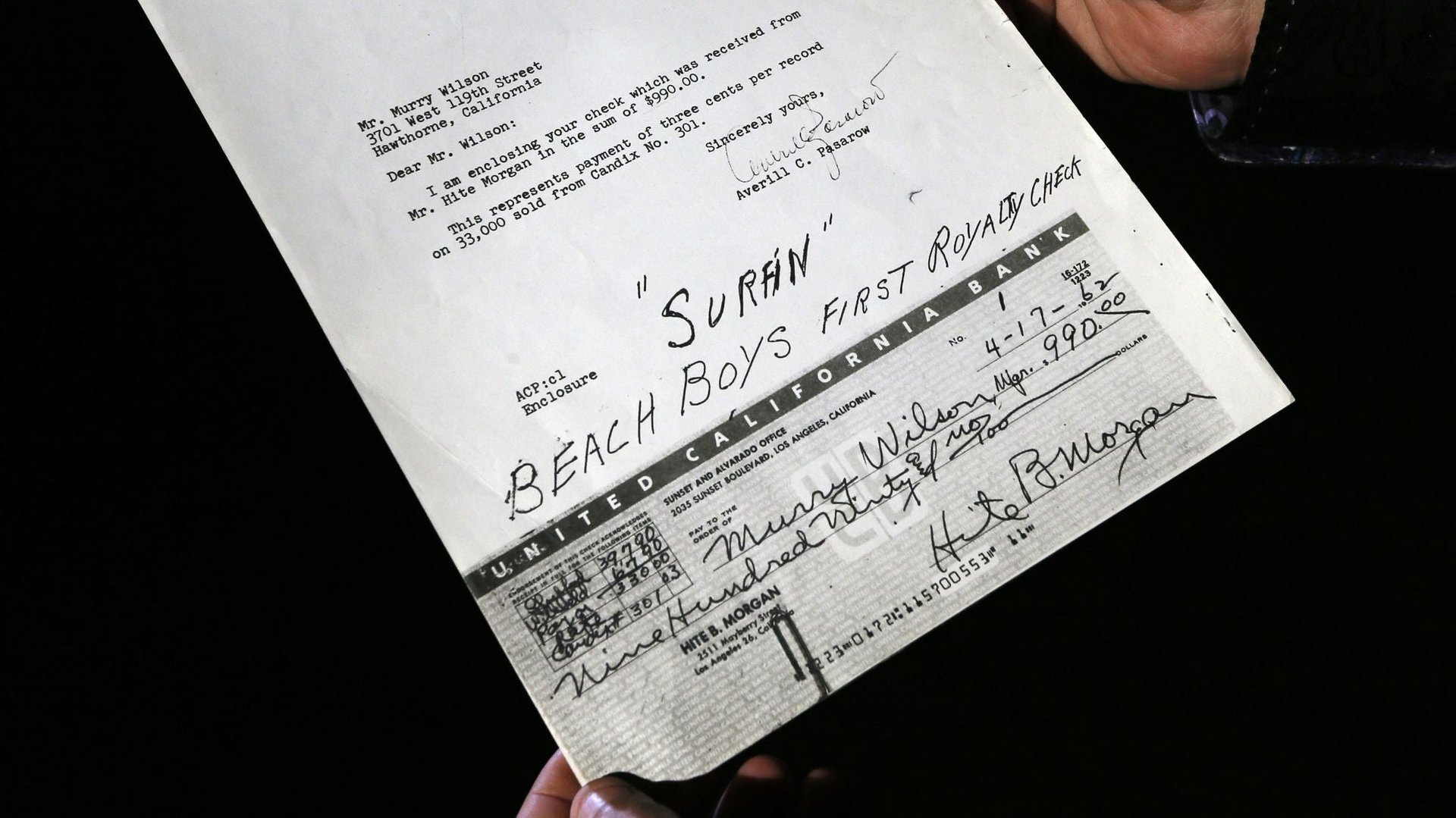

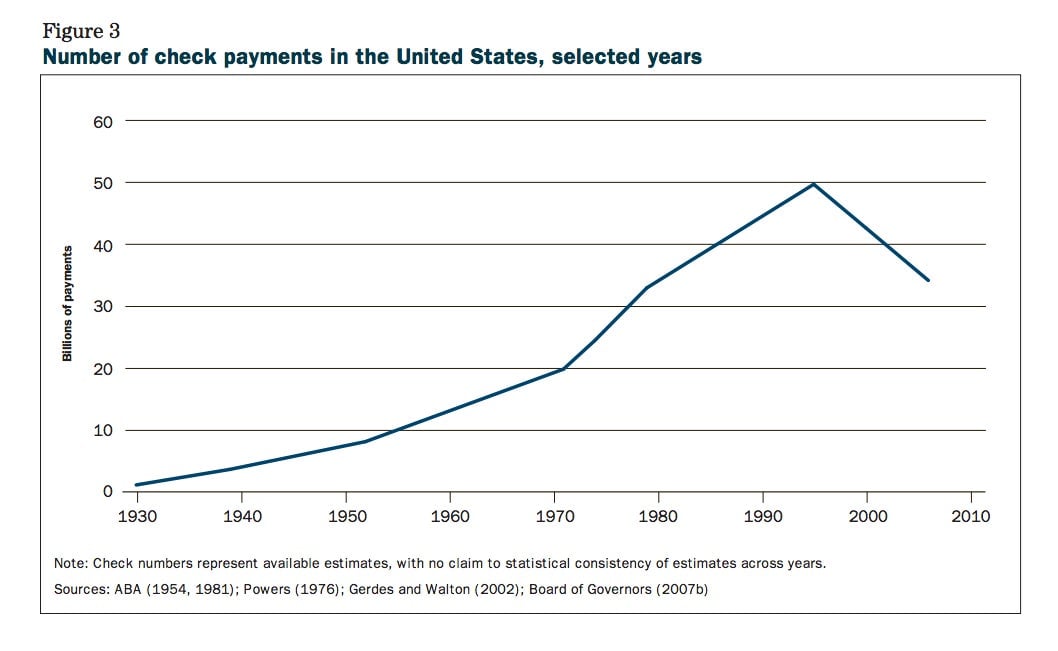

There was a time when checks were the hot new payment technology. In the years after World War II, newly affluent American households adopted check writing like never before. The overall number of checking accounts in the US doubled between 1939 and 1952, rising to 47 million. The number of checks written hit about 8 billion in 1952.

At the time, checks were still processed manually. Some 28 million checks were being written every day, with each one having to go through an average of 2.5 banks to be processed, according to one study. Unless a check was deposited at a bank that was home to both parties in a transaction, it had to be sorted by hand and tallied on an adding machine at least six times before it was cleared. At a 40-person bank branch, at least seven people worked to tally, process, and bundle checks. A solution was needed.

Officials at Bank of America were the first to try to do something about it. In the 1950s they asked the Stanford Research Institute to come up with a solution. The result? The Electronic Recording Machine, Accounting system, or ERMA, which was introduced in 1955. Along with ERMA came those funny-shaped letters—the font is known as E13B—that are still used at the bottom of checks. Known as magnetic ink character-recognition code, or MICR, this code enabled computers to read and process checks. (ERMA was one of the first large-scale general computing systems designed for the financial industry, setting the stage for everything from ATMs to e-commerce.)

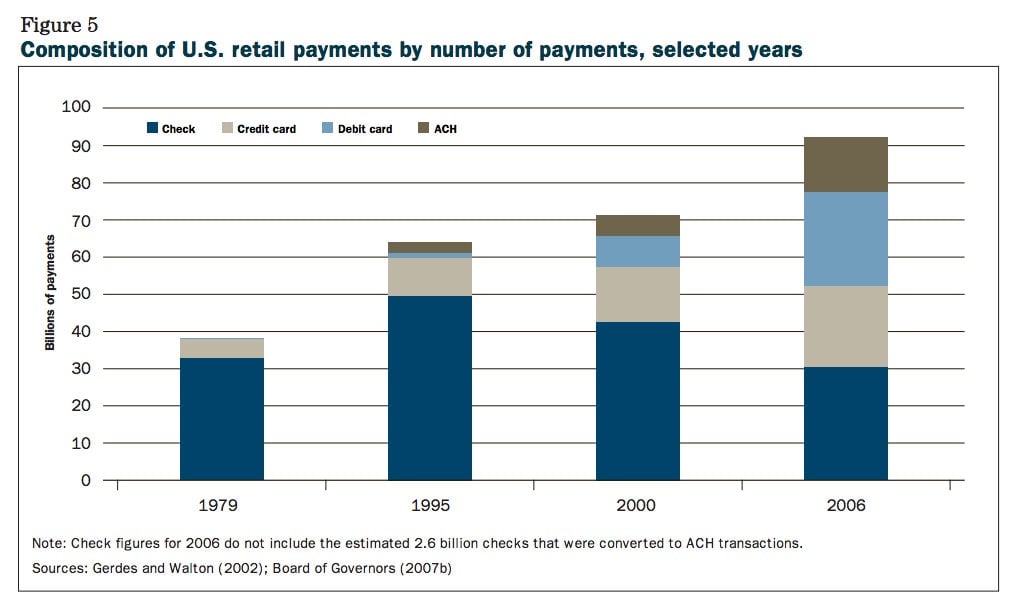

The arrival of MICR, which became the industry standard in 1967, helped drive check-processing times below two days during the 1970s, according to a Fed report (pdf). Those improvements in processing times made checks a more viable option for a range of household payments. The number of checks written surged to nearly 33 billion by the end of 1979. That year, checks made up roughly 86% of all non-cash payments, according to a separate report (pdf).

But the check’s days as king of the cash alternatives were numbered. While the number of check payments continued to rise into the mid 1990s—they peaked at an estimated 49.5 billion in 1995—checks began to lose significant market share to alternative forms of payment like debit and credit cards and direct, electronic, automatic clearinghouse payments (ACH).

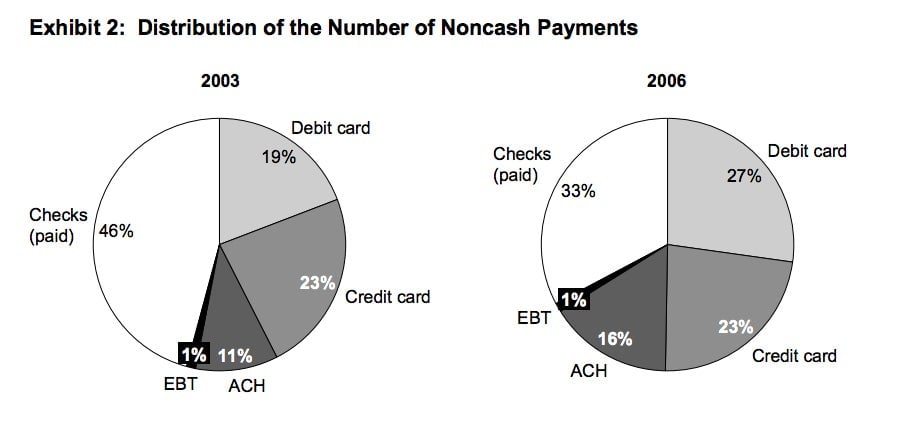

The trend toward electronic payments only gathered pace, and by 2003, the Fed estimated (pdf) that other forms of payment had overtaken checks in usage. And by 2006, checks accounted for barely one-third (pdf) of non-cash payments in the US.

Consumer preferences seem to be a key driver of the trend. According to the Fed, debit cards and credit cards are by far consumers’ favorite way to make payments. Some 43% of the consumers surveyed by the Fed said debit was their preferred method of payment. Another 22% preferred using credit cards. A solid 30% preferred cash. Checks? Only 3% of the people who took part in the Fed study preferred using checks. (Check preference was highly correlated with older consumers.)

And interestingly, the Fed study notes that consumers who do prefer using checks actually end up using cash twice as often. “This may reflect subtle (and not so subtle) social pressures to use a faster alternative to the check for the point of sale transactions that make up a large share of consumers’ everyday expenditures,” the Fed study said.

For banks and retailers, the very distinction between checks and electronic forms of payment has become blurry. Checks are now regularly scanned for MICR information and converted into automated clearinghouse transactions. The passage of a new law in 2003 also enabled payments to be made using electronic images of checks; previously, the physical check itself had to be transported and presented for clearing. A 2007 survey estimated about 40% of checks were “electronified,” according to the Fed, which admits that likely understates the true number. “Industry observers widely predict that traditional paper processing will be phased out over the next few years,” concluded the Federal Reserve back in 2008 (pdf).