Everything that’s wrong with relying on employers for abortion access

In the US, about 50% of Americans receive health insurance through their employer. That means where you work often plays an outsize role in determining the medical care you’re able to receive.

In the US, about 50% of Americans receive health insurance through their employer. That means where you work often plays an outsize role in determining the medical care you’re able to receive.

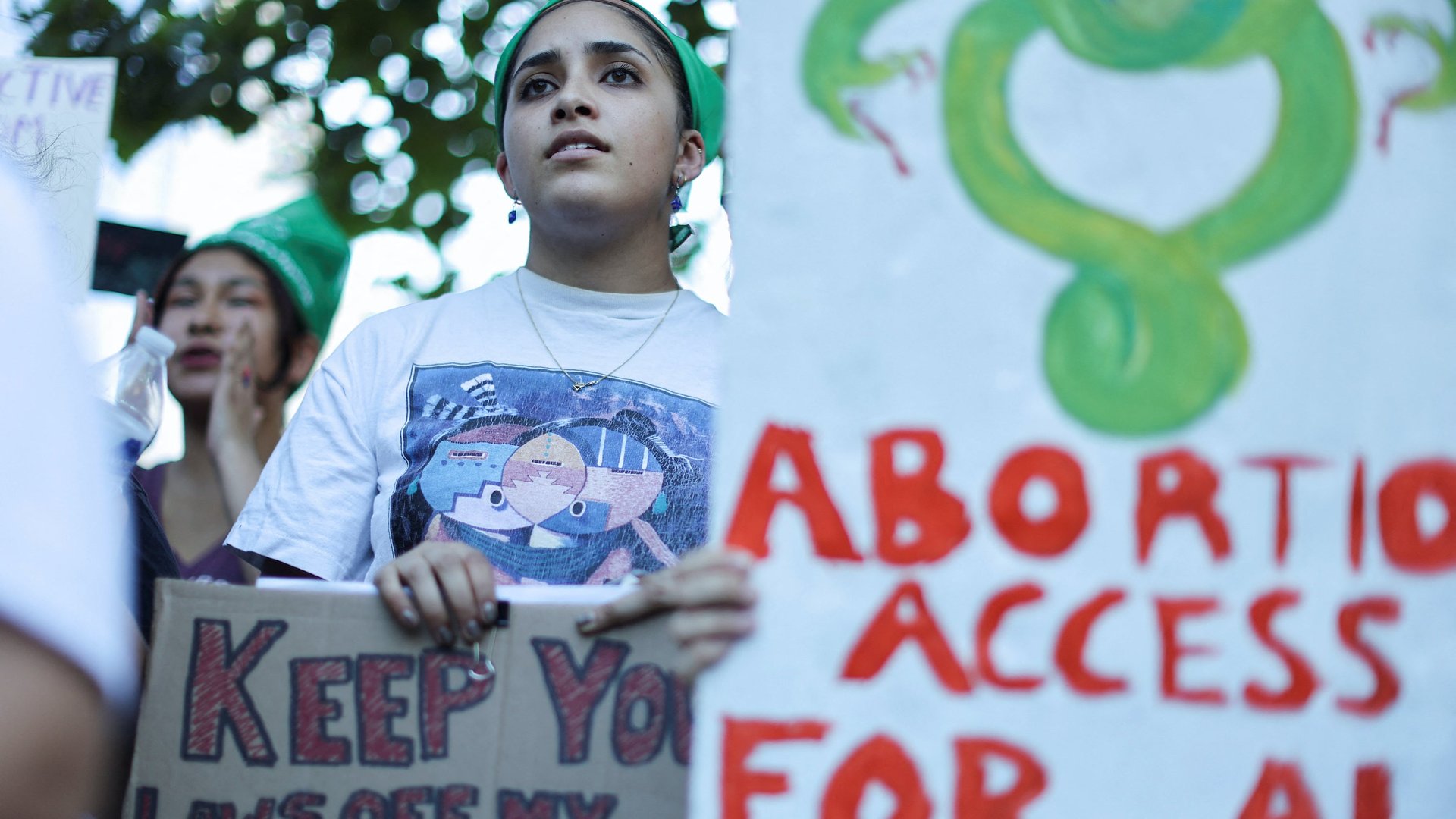

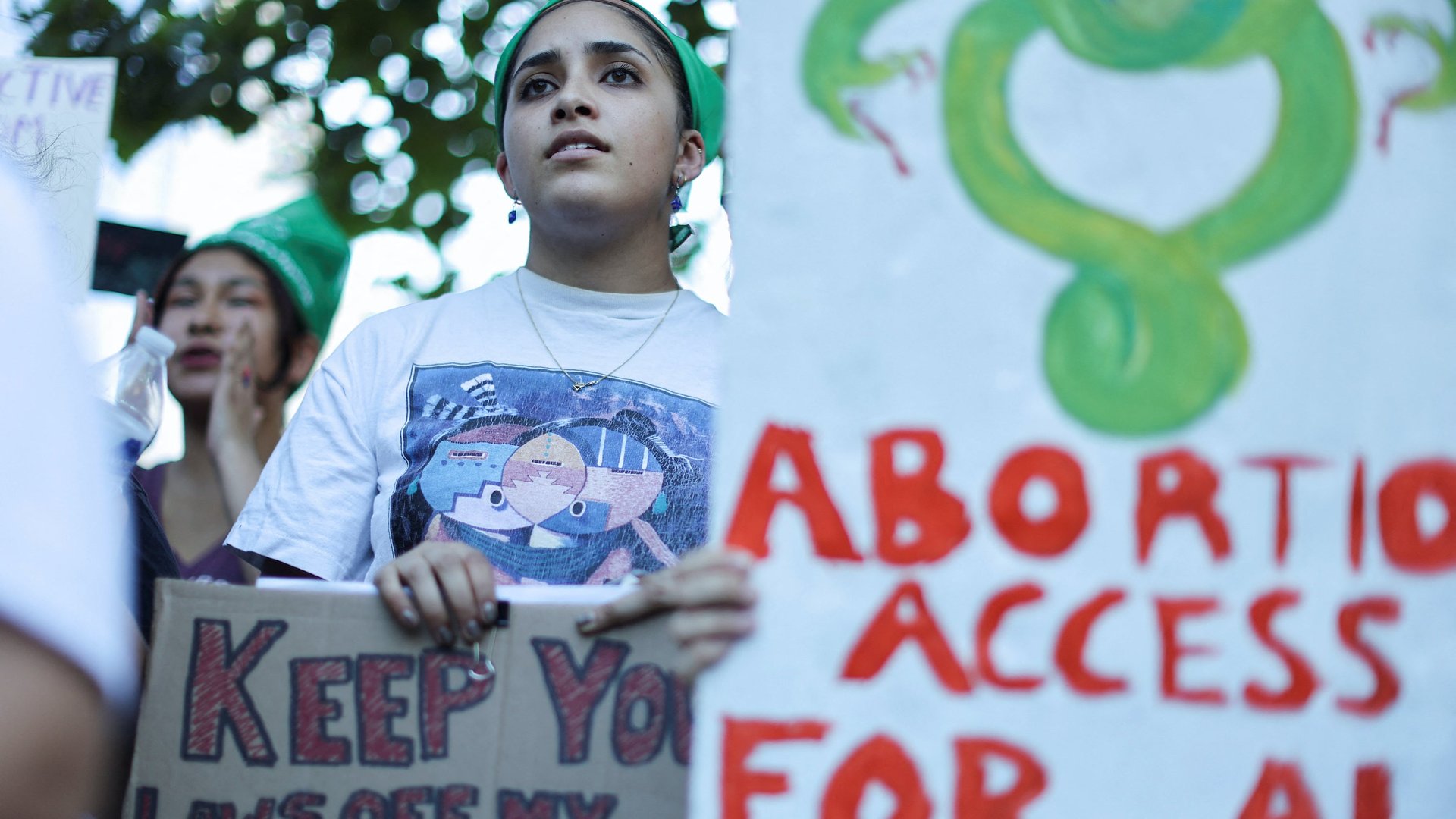

The Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade will only further entrench this dynamic, with companies including Meta, Disney and JPMorgan Chase announcing new travel benefits aimed at helping employees access reproductive healthcare.

This development is troubling on a number of levels. A system in which people can only have an abortion if they happen to work for an employer who is willing to cover their travel costs and give them paid leave has dire implications for exacerbating health and economic inequities in the US. And privacy and confidentiality issues will inevitably arise when employers take on responsibility for helping workers gain abortion access.

“No one is comfortable with this being the backstop on access to reproductive health care, never mind abortion care,” says Erika Seth Davies, CEO of the social impact firm Rhia Ventures, which is focused on women’s and reproductive health. “But that is where we are in the face of this systemic failure of the federal government, which at no point in the last 50 years ensured protection with federal legislation to enshrine abortion access or abortion care as a right.”

What happens to low-income workers who need abortion access?

Anyone with a uterus, including middle-class and wealthy women, may be vulnerable to the fallout from the Supreme Court’s decision. But given that three-quarters of abortion patients are at or near the federal poverty level, lower-income workers (a group that includes a disproportionate number of women of color) are particularly likely to be impacted by the downfall of Roe.

Many of the companies now offering abortion-care benefits, like Salesforce and HP Enterprise, primarily employ white-collar workers. Marginalized people, by contrast, often “work for companies that are not stepping up” with offerings like paid family leave or paid sick leave, let alone travel funding for abortion care, says Shaina Goodman, director for reproductive health and rights at the National Partnership for Women & Families.

Meanwhile, domestic workers, undocumented immigrants, and part-time, contract, and gig workers are all less likely to be eligible for reproductive healthcare benefits through their employers. And lower-income workers who want abortions but can’t access them are likely to face even greater financial difficulties as they struggle to care for expanding families on already-tight budgets, an outcome that will further exacerbate economic inequalities in the US.

“I think, unfortunately, this will result in two tiers: the people who have the resources to get the care they need, and the people who don’t,” says Davies. She says that the deepening link between employment status and abortion access is particularly concerning given that under the Hyde Amendment, first passed in 1976, federal funds cannot be used for abortions—further limiting access for people on Medicaid and other government health insurance programs.

There are steps companies can take to try to mitigate the inequity of abortion access. Goodman recommends that companies take a close look at their political contributions, and consider long-term investments in abortion funds and reproductive justice organizations. As just one example, online dating companies Bumble and Match, both of which are women-led firms based in Texas, created relief funds in the wake of the state’s abortion ban, channeling money toward organizations that offer support for people seeking abortions.

“It’s wonderful but insufficient to do things that just take care of your own workforce,” Goodman says.

Employer-provided abortion benefits raise privacy concerns

As employers take on new roles in providing access to reproductive healthcare, privacy and confidentiality issues are another obvious concern. “If I want to access a travel fund that my employer has set up, what am I going to have to disclose and where is that information going to go?” Goodman asks.

People seeking abortions, or helping others to access them, could face the risk of civil or criminal prosecution in some states. And given the stigma still associated with the procedure, many people might also worry about facing backlash if they have to inform their manager or HR department that they need to tap into the travel funds. (Employers can’t legally discriminate against workers for having an abortion or for choosing not to have one, but biases might well manifest anyway.)

In an effort to get ahead of such complications, the US Office of Personnel Management announced two privacy measures accompanying a new policy that will allow federal employees to use paid sick leave to travel for healthcare. Employees won’t be required to provide any medical documentation or reason for absences under three days. And doctor’s notes provided for longer sick leave need not provide specifics about the nature of the procedure or treatment.

As a practical means of distancing themselves from knowledge about which employees are using which benefits, many companies will likely lean on third-party insurance providers they already use for healthcare and other benefits, according to Jen Stark, co-director of the BSR’s Center for Business & Social Justice. The online directory Yelp has already announced one such plan. “Companies will want to stand up systems where they’re a step removed, where there is no expectation that workers would have to reveal any kind of healthcare procedure,” Stark says.

What abortion benefits mean for the future of employee organizing

In a May 2022 survey conducted by Gartner, 60% of 78 employers said that they did not have plans to offer any new healthcare benefits if Roe v. Wade was overturned. Such employers may not be aware of how employees are being affected by restrictions on reproductive care, given that abortion is a sensitive subject for workers to broach.

“People are already anxious about taking sick leave,” Davies points out. “Who’s going to go to HR demanding abortion coverage for themselves or other people?”

Amid rising interest in unions and other forms of employee activism in the US, collective bargaining could provide workers with a way to gain abortion benefits without putting any one individual in a vulnerable position. But Davies says she’s also concerned about the possibility of employers holding benefits over employees’ heads as a means of shutting down union activity. “What’s to stop any employer that has agreed to provide travel vouchers but is opposed to union organizing from using that as a bargaining chip?” she asks.

Some confusion over this very point is currently playing out at Starbucks, which has confirmed that travel benefits for workers who need abortion will be available to employees at unionized stores. But the company also says in a letter posted on its website that it “cannot make promises or guarantees about any benefits” in stores represented by unions: “For example, even if we were to offer a certain benefit at the bargaining table, a union could decide to exchange it for something else.”

This caveat has been interpreted by some as a scare tactic meant to dissuade employers from organizing, particularly in the context of reports that some Starbucks managers have told employees that trans healthcare benefits could be taken away if they unionize. Starbucks says that it’s not threatening to take benefits away, but rather making the point that “it’s difficult to predict the outcome of negotiations.”

Abortion access and the future of work

Reproductive-rights advocates say it’s commendable that some businesses are coming forward with ways to support abortion access and, in the cases of companies like Yelp and Conde Nast, outright condemnations of the Roe decision and the impact it will have on women’s health. Patagonia has even promised to bail out employees who are arrested while participating in peaceful protests for reproductive rights, noting that “caring for employees extends beyond basic health insurance.”

But Stark says that seeing companies come forward now is also a reminder that businesses, long hesitant to wade into discussions about abortion, could have done more to prevent the overturning of Roe and state abortion bans in the first place. “If companies had engaged this robustly a decade ago, we wouldn’t be where we are now,” Stark says.

That said, it’s not too late for companies to engage in political pushback against abortion restrictions. “If companies don’t want to be in this position, they need to get on the phone with policy makers and ensure the Women’s Health Protection Act is enacted,” Davies says, referring to legislation that would enshrine federal protection for abortion rights in US law. The bill was passed by the House last fall but voted down by the Senate in May.

For everyone else, the ways in which the Supreme Court’s decision has made workers even more dependent upon their employers may underscore the need to push for a bigger, better social safety net. Says Goodman: “I think this opens up a much, much bigger question about the future of work, and what does it mean for so much of our lives to be structured around where we’re employed?”