Is the design sector really still an all-boys club? A new report from the UK Design Council implies as much.

The Design Economy: The People, Places and Economic Value, published by the London-based charity this week, found that 77% of the country’s estimated 1.6 million designers identify as male—an imbalance that has persisted since 2016. The report’s authors consulted data from the UK Office for National Statistics and workforce sites like the O-Net labor database. They also polled 1,300 UK-based designers, party to account for transgender or non-binary respondents that the publicly available data don’t account for. In the survey, 2% identified as non-binary and 0.8% as transgender.

While the 77% number is alarming, understanding the Design Council’s findings requires digging into the nuance.

First, design is a broad sector. It encompasses a hodge-podge of disciplines like architecture, graphics, typography, fashion, furniture design, web design, theater design, pottery, urban planning, even advertising—and men don’t dominate every specialization.

For instance, while 88% of product and industrial designers in the UK identify as male, 80% of dressmakers are female. Similarly, 81% in architecture are male, but females dominate graphic design.

The tech design sector is mostly male

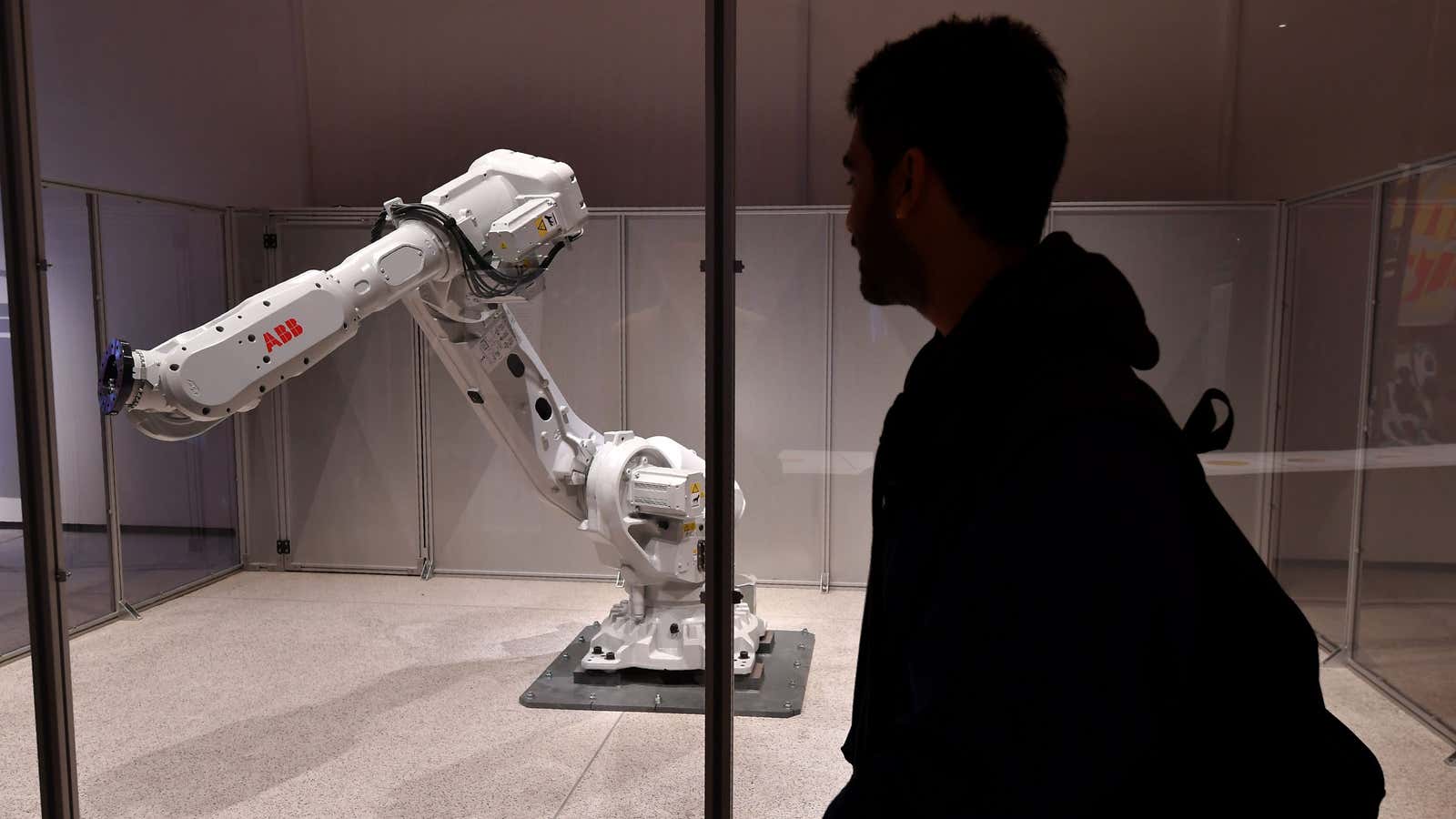

The gender disparity is most glaring is the male-dominated digital design sector, which now represents the largest subset of design professionals in the UK, filling 870,000 jobs. Digital design encompasses tech sector workers who go by titles like app designers, front-end web developers, systems architects, or video game designers. Design Council’s research mirrors the well-known gender imbalance in the broader tech industry.

Why does diversity in the digital design sector matter?

With tech seeping into every aspect of our everyday life, we need a diverse pool of digital designers more than ever, the Design Council argues. “The design workforce needs to reflect the diversity of the world it designs for,” they explain. “If it does not, the design of products, places, and services can overlook the aspirations, assets and needs of many people, excluding them and reinforcing existing inequalities and forms of marginalization.”