A 900-year-old map isn’t the best way to draw borders in the South China Sea

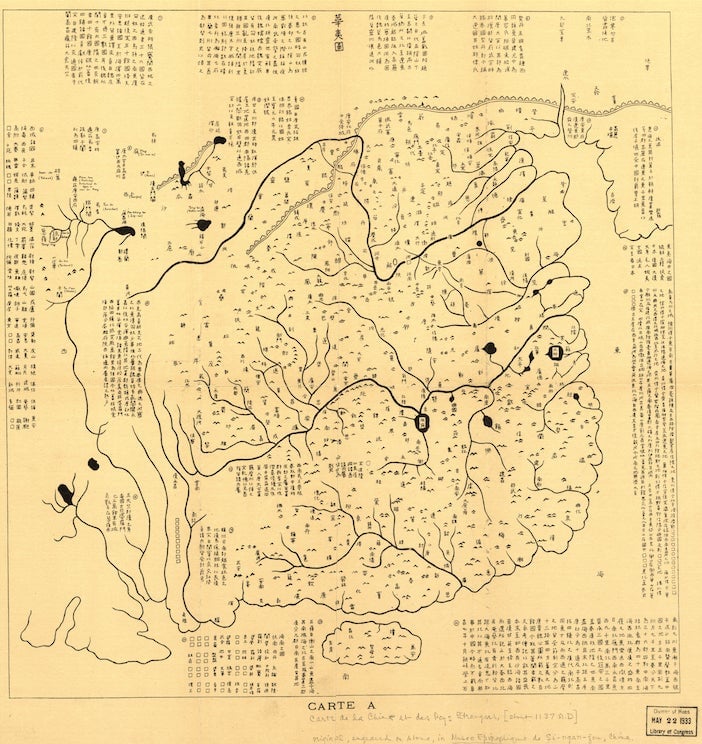

This Chinese map, made from rubbing of a stone engraved in 1136 AD, depicts China’s reach as described in the Yu Gong, an ancient text that dates back to the fifth century B.C. Even though the drawing is clearly ancient history, it and other maps from dynasties and centuries past are resurfacing in the volatile debate over the South China Sea.

This Chinese map, made from rubbing of a stone engraved in 1136 AD, depicts China’s reach as described in the Yu Gong, an ancient text that dates back to the fifth century B.C. Even though the drawing is clearly ancient history, it and other maps from dynasties and centuries past are resurfacing in the volatile debate over the South China Sea.

In a lecture last week in Manila, a Supreme Court judge in the Philippines said the map and other old texts provide clear proof that the China’s extensive claims in the South China Sea are a “giant historical fraud.” That’s because they show China’s southern territorial reach traditionally ended at the island of Hainan.

As China has moved more aggressively on its claims in the South China Sea in recent months, putting an oil rig in disputed territory with Vietnam and building permanent structures on islands claimed by the Philippines, Southeast Asian nations have responded with a combination of entreaties to the United Nations and a full-on publicity campaign. The latter includes everything from YouTube videos to lectures, many of which rely on cartographic records from hundreds of years ago.

This particular map, which can be viewed in the US Library of Congress’s vast online archive, is titled Hua Yitu (华夷图), which directly translated means “Map of China and the Surrounding Countries.” (Because the character yi can be read to mean minority groups, or at least non-Han Chinese, the diagram could also be called “Map of the Han People and the Minorities.”) An explanation on the map says that the southern border of the empire’s reach is the Zhang Sea, which many scholars believe is an ancient Chinese name for the South China Sea.

But that doesn’t carry much weight in the current territorial dispute, analysts say. When it comes to international law of the seas, most maps are “just information,” Francois-Xavier Bonnet, a geographer with Bangkok’s Research Institute on Contemporary Southeast Asia told the Voice of America. “They give information for one period and it’s not a legal document,” he said. By the early 1900s, China had included the Paracel Islands to its maps as the southern-most border, and it added the Spratley Islands in 1935 (today, the control of both is a matter of dispute), he pointed out.

The ancient stone map is part of a larger carving that is itself drawn from the Yu Gong, which “describes an archaic, unified China defined by rivers and mountains,” as Time magazine explains. So even when it was made, the map reflected a “legendary, lost China,” not the country’s borders at the time.

That’s probably a good thing for China’s neighbors. The map the Philippines is using to try to prove China’s territory ends at Hainan Island also claims that “Rinan Jun” belongs to China. Rinan Jun is an ancient Han Chinese prefecture that is now firmly in central Vietnam.