A new kindergarten on a tiny island is Beijing’s latest South China Sea incursion

As public tensions between Beijing and its neighbors over disputed territory in the South China Sea simmer, Chinese authorities made a quiet incursion this weekend: construction began for a kindergarten and primary school on the remote, idyllic island of Yongxing, the largest of the Paracel Islands.

As public tensions between Beijing and its neighbors over disputed territory in the South China Sea simmer, Chinese authorities made a quiet incursion this weekend: construction began for a kindergarten and primary school on the remote, idyllic island of Yongxing, the largest of the Paracel Islands.

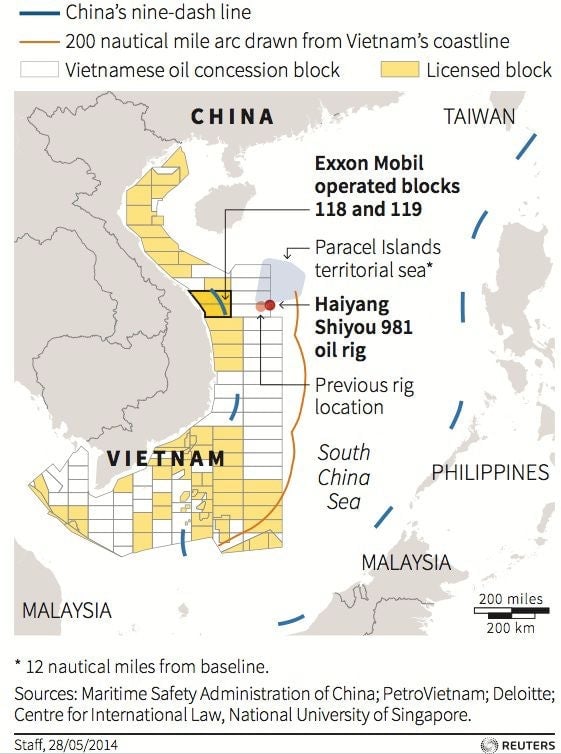

The island, which China calls “Yongxing” (literally “eternal prosperity”), is less than one square mile in size, but it highlights one of the most contentious aspects of international law regarding who can claim what territory in the world’s oceans. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), signed by most of the Asian claimants involved in the South China Sea disputes, says that a state is entitled to explore and exploit all the natural resources within 200 nautical miles of its islands’ baselines via an “exclusive economic zone.” Unfortunately, the 1982 convention never laid out how to determine sovereignty over an offshore island.

That lack of clarity is one reason why China—established the city of Sansha on Yongxing in 2012—along with Taiwan and Vietnam have set up varying forms of outposts on the Paracel and Spratly island chains, believed to be home to untapped oil and gas reserves. (It’s also why countries are resorting to ancient maps and historical texts to make their claims, which as we’ve as we’ve noted, isn’t the best idea.) “China’s end game is to have de facto—if not de jure —control over adjacent waters, the Western Pacific,” Richard Javad Heydarian, a lecturer from Ateneo de Manila University, told Bloomberg.

The Paracels, where Yongxing is located, are about 26 nautical miles from where China has parked an oil rig that has been the source of clashes with Vietnam. China is also reportedly building an artificial island on the Johnson South Reef in the Spratly Islands. (Though, according to the UNCLOS, artificial islands don’t have the same status as natural islands and are not entitled to any exclusive maritime zones.)

But, to gain rights to an exclusive economic zone surrounding, for instance, Yongxing, China has to first prove that this little slice of heaven fits the UN”s definition of an island, namely that it can support human and economic activity. This is likely why China has been pouring billions of yuan into equipping Yongxing with roads, an airport, a hospital, banks, a supermarket, a post office, 24-hour satellite television network and cell phone coverage, and now, a school.

Unfortunately for China, this strategy hasn’t always held up in court. In 2009, Romania and Ukraine were locked in a dispute over whether the rocky islet of Snake Island, home to a small Ukrainian population, counted as an island and permitted Ukrainian jurisdiction in the surrounding waters. Despite Ukraine’s claims that the area was “an island with appropriate buildings and accommodation for an active population,” the International Court of Justice ruled in Romania’s favor.