Progressive new legislation meant to improve gender diversity on India’s corporate boards risks being undermined by a traditional bedrock of business in India—family.

In 2013, India enacted a new Companies Act, replacing the original 1956 law. It mandated that all companies listed on stock exchanges must have at least one woman on its board of directors. The rationale was obvious. When it came to gender balance, India’s corporate boards came woefully short. More than 60% of the 1,461 companies listed on the National Stock Exchange do not have a single woman member on their board of directors.

Yesterday, India’s second-largest private sector conglomerate by market cap, Reliance Industries Ltd, named a woman to its board, well ahead of the October deadline to comply with the new norms. She is married to billionaire company chairman Mukesh Ambani.

Reliance can of course name to the company board whoever its shareholders deem fit. But the move by the large corporation confirmed what many feared would be the route companies would chart to comply with the law—nominate members of the promoter family to the board.

“It shows corporates are not ready to diversify in the true sense of the word,” says Ranjana Agarwal, India chair of Women Corporate Directors, a global community of women directors, and a former president of the FICCI Ladies Organisation. “They don’t want any dissent on their board and want to remain an old boys’ club.”

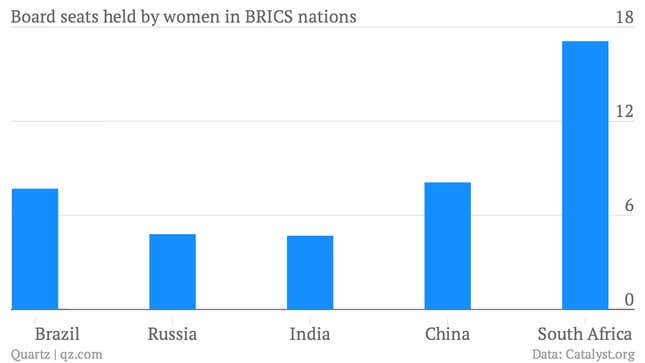

Even though India is Asia’s third largest economy, companies here have not made much of an effort to include women in their growth story. Women in India, according to research firm Catalyst, hold barely 5% of board seats—lower than all other BRICS countries. In the United States, 17% of the board members are women.

Norway is the leader in corporate gender diversity. Women hold more than 40% of the board seats in the European country. In 2006, Norway passed a law requiring 40% of boardroom seats to go to women.

India is not even close to that sort of an inclusion.

Most corporates had protested against mandating the appointment of even a single woman director because they felt that the pipeline of qualified women is small, according to Agarwal. As a result of their lobbying, they got the next best option: a chance to keep it all in the family and not have to search for an independent woman director.

The industry body, PHD Chamber, conducted a survey on gender diversity by interviewing 66 board members in India in 2011. Almost one-fourth of companies without female directors felt that women are not mentally tough enough to handle the job.

If more companies end up taking the family route, the well-intentioned law will result in a perverse consequence—boards with greater representation from the promoter family.