The not-so-surprising secret to happy children: parents who smile

The other day, a mother of a 15-month-old walked into Andrew Garner’s office, oozing frustration.

The other day, a mother of a 15-month-old walked into Andrew Garner’s office, oozing frustration.

“Is it normal for them to never sit still?” she asked.

Garner, a pediatrician in Westlake, Ohio, leapt on the remark as a teachable moment.

“He doesn’t sit still?!” he said, “That’s a compliment to you! You want him to do that.”

At 15 months, he explained, children are itching to explore, and then toddle back, and then wander off again. It’s a sign the baby is developing apace.

The goal is to make the woman feel confident in her mothering abilities. If he builds up her self-esteem, Garner hopes, she’ll be more invested and engaged as a mom, and the child will grow up smarter and healthier as a result. Garner bases this chain of events on a spate of recent studies that have shown that supportive parents breed better-off children.

So, now, on top of taking measurements, asking about sleep and food habits, and giving vaccinations, Garner devotes part of the visit to checking up on mom. Particularly if the family comes from a harsh environment or if the mother shows signs of depression, he tells her to make sure “you’re smiling at your baby, you’re being aware of your emotions, and using positive discipline techniques.”

“I tell them things like that tantrums are emotional overload and not how they feel about you,” said Garner, who is also an associate professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University. “Or at 12 months, I spend a lot of time talking about the fact that they’re soon going to want to prove they can do stuff.”

Garner knows that if the mom gets angry about the child’s normal behavior, she might develop a negative attitude toward parenting. And that could be poisonous in a very real way. Pediatricians are growing increasingly alarmed about the dangers of so-called “toxic stress”—certain kinds of childhood experiences, like turmoil, violence, and neglect, that, when chronic, can alter brain structure and chemistry and hurt a child’s chances of long-term success. Harsh parenting by itself won’t necessarily doom a child, but when combined with other stressors, it might.

“When bad things happen early in life, whether you remember them or not, the brain doesn’t forget,” Jack Shonkoff, a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, said at a recent conference in Washington, DC.

When we experience everyday stress, our bodies kick into high gear by releasing adrenaline and cortisol. When the stress goes away—or if, as children, we’re comforted by trusted adults—our bodies return to normal. But if there is no adult around, or the stressors are ongoing, the response system stays activated. This chronic, “toxic stress” throws the brain into a permanent state of high alert, weakening the neural connections that are essential for learning and cognition.

“It’s not black and white. It’s not like the baby gets hosed for life if you’re not smiling at it,” Garner said. “But our brains and our genome are very plastic early in life. They’re taking in cues to prepare us for what’s coming.”

Experience influences which genes get switched on and the way our brains anticipate the future. A child tumbling through the toxic stress cycle might have a brain that’s ready for “a dog-eat-dog world. That child will be more hypervigilant, anxious, on edge and less likely to learn as easily as another child will,” he added.

Studies show that children who are exposed to toxic stress fare worse over the course of their lives. Family poverty is strongly correlated with lower cognitive test scores, even when controlling for the mother’s education and other family factors. Children who are neglected have worse executive functioning, attention, processing speed, language, memory, and social skills. People who are mistreated as children are more likely to suffer from heart disease as adults. Our brains and genomes are particularly sensitive during so-called “critical periods”—the times during early childhood when the brain is rapidly changing.

Poverty is the most common reason why Garner’s patients’ moms have a harder time mothering. Maslow’s Hierarchy dictates that if food, shelter, safety, and other essentials aren’t in place, there will be a dearth of brain space for bedtime stories and positive affirmations.

Still, other moms might flag in supportiveness because their jobs are too demanding or because they have postpartum depression. Garner says he’s even seen the reverse of poverty turn harmful: Two uber-successful parents spending their free time twiddling on their phones rather than attending to their newborn.

About 10 years ago, Joan Luby, a psychiatry professor at the Washington University School of Medicine, invited 92 children between the ages of four and seven to a lab in St. Louis. The kids took a test that measured whether they were depressed—some were, and some weren’t. One by one, the children and their primary caregivers (in most cases, the mom) were invited into a room that contained a brightly wrapped gift with a bow on top. A research assistant told the children they could have the gift if they waited patiently for eight minutes. In the meantime, the mother was told to fill out a daunting stack of complicated forms. Annnd … go!

As expected, the kids went bonkers. They begged. They whined. They stretched their tiny hands toward the box. They, being kids, yearned for nothing more than to rip it open.

But the researchers’ eyes were on the parents. Some of the moms were supportive, telling their little eager beavers “that they knew it was hard to wait. Or they touched them or said something reassuring, might have even given them positive feedback for being patient,” Luby told me.

The other moms were too overwhelmed by the forms to be comforting. They were unresponsive to their child’s pleas and they didn’t reassure them. Some snapped at or hit their child for being annoying.

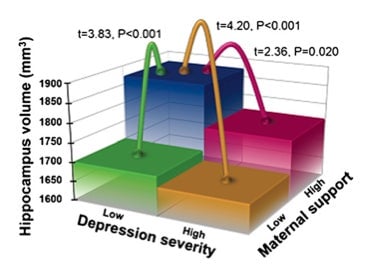

When Luby and her colleagues conducted an MRI four years later, they found that the non-depressed children whose mothers had not been nurturing had smaller hippocampuses than the kids who were depressed but had levels of high maternal support. In other words, it was better for the kids to be depressed, with supportive moms, than not depressed, with unsupportive moms. Since the hippocampus governs things like memory, cognitive function, and emotion, the smaller hippocampal volume suggested to Luby that the children with the non-supportive moms were doing worse both cognitively and emotionally.

“What was exciting about this finding is that it showed that early nurturance was having a material effect on tangible brain outcomes,” Luby said.

It’s this type of evidence that led the American Academy of Pediatrics to announce this week that all parents should read aloud to their children from birth—the first time the group has ever weighed in on early literacy. The recommendation was based in part on findings that wealthier people hear millions more words than low-income people do as children, and that this verbal difference translates to a big gap in school test scores.

***

Of course, all the good advice in the world won’t help a parent who is scraping by financially, doesn’t have a safe home, or is otherwise strained. Denise Dowd, who works at Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Missouri, mentors mothers who are victims of poverty and domestic violence. “You can’t imagine what they’re going through,” she told me “We’re talking about not just sexual abuse, but your mother selling you into prostitution, your mother shooting you up for the first time when you’re 12 so you can get through your first tricks okay.”

In the words of these mothers, “you can never give what you never got.” Many of them think it’s sufficient just to keep their children safe, dry, and fed. One told Dowd didn’t know she was supposed to talk to her baby.

And as a result, the kids are also “dysregulated,” as Dowd puts it. “You have 3- and 4-year-olds who have no ability to sit still, who will curse you out, who give you finger.”

“The very resources the moms need to handle those stressors—the ability to predict, the ability to remain calm and think through a set of problems—that’s the prefrontal cortex and that really takes a hit when you’ve been exposed to abuse and neglect,” she added.

Most babies start to smile at their moms at six weeks. Garner said he tries to tell moms to smile back. But it’s hard—they might be clinically depressed or just too tired to be happy.

“Those first six weeks are pretty brutal for the mom—the babies are peeing, pooping, sleeping blobs,” he said. “You’re exhausted, you’re sleep deprived, there are hormonal changes, and you have expectations for motherhood that are not being met.”

So he tries to explain to parents how reinforcing their kids’ happy behaviors can lead to an easier time of parenting down the road. “Every time the baby tries to get your attention with a happy sound, give them your eyes,” he said. “At 18 months, they’re like little scientists. If every time they make a happy sound, moms gives me her eyes, I’m going to make happy sounds. But if the only time mom gives me attention is when I scream bloody murder …” scream is just what the baby’s going to do.

Dowd tries to show moms how resilient they are—“what’s strong about themselves.” The hope is they’ll want to defy their own bitter upbringings by raising kids who are functional and happy.

Garner said the US should also increase spending on social services and better integrate social programs into the healthcare system. As political science professor Kimberly Morgan wrote in Foreign Affairs last year, “In Australia, more than a third of direct public spending goes to means-tested programs, and in Canada and the United Kingdom, almost a quarter does.” In the US, however, the figure is 7%.

The final hurdle is that there are very few ways ensure the mothers practice the good parenting practices they learn after they return home. Services like Text4Baby can send mothers safety tips and appointment reminders, but there’s not an app for “I’m so stressed out because I just got laid off and my toddler won’t stop crying.”

Garner says what vexes him and other pediatricians is trying to find the delicate balance between getting to “good enough” parenting without coming off as condescending, all while environmental factors work against doctor, mom, and baby alike.

“I’m not saying there’s only one way to parent,” he said. “This isn’t about values or character. This is about skill formation. What are the essential skills we need to model and teach and nurture in our children so that they have a shot?