These charts suggest Asia might be heading for a new debt crisis

In Asia, private sector credit is at an all time high. According to London consultancy Capital Economics, the continent could be heading for a new major debt crisis (here is a reminder of the continent’s mid 1990s financial meltdown). Capital Economics says China, Hong Kong and Vietnam look in the worst shape. Here is their argument, in charts from their research note:

In Asia, private sector credit is at an all time high. According to London consultancy Capital Economics, the continent could be heading for a new major debt crisis (here is a reminder of the continent’s mid 1990s financial meltdown). Capital Economics says China, Hong Kong and Vietnam look in the worst shape. Here is their argument, in charts from their research note:

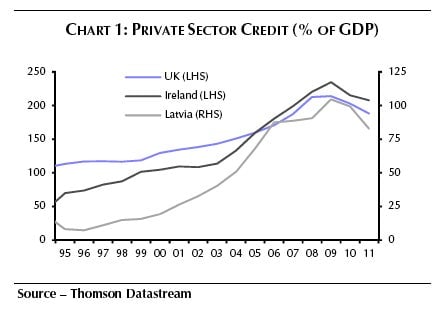

1) In Hong Kong, a rapid explosion of credit over the last few years looks similar to what happened in Ireland, the UK and Latvia just before these nations’ financial systems imploded.

Here is the credit expansion that occurred in the three European countries:

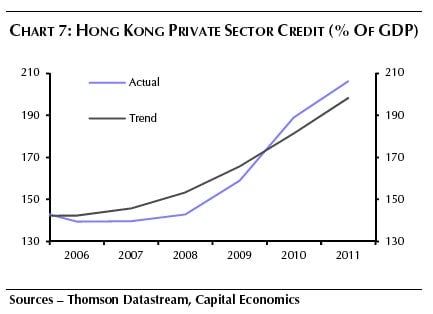

Things are looking similar in Hong Kong:

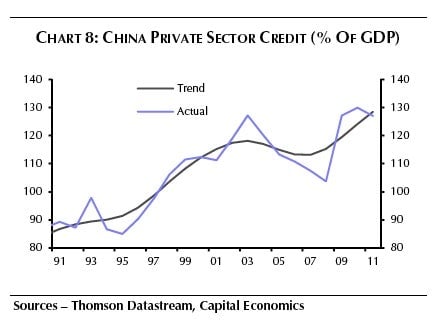

And China:

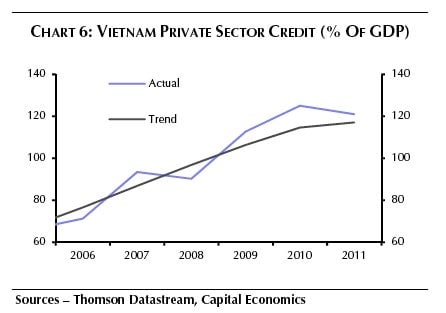

And Vietnam:

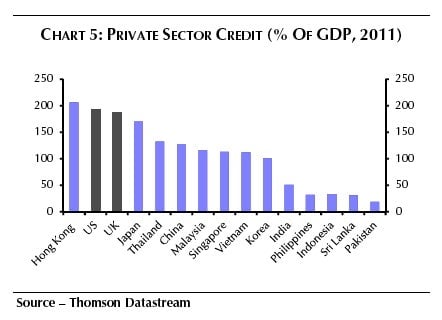

Meanwhile, Hong Kong now has a higher private sector credit to GDP ratio than the US, the UK and most of Asia.

Now, are these charts too alarmist?

Vietnam could well be heading towards a crisis. Hong Kong does not seem in bad shape. China does not have the same property, stock market or consumer spending bubbles that were features of the European pre-crisis boom, though it does have a seriously disturbed banking sector that could drag the economy down with it.

Vietnam’s potential economic meltdown is rooted in the banking sector. Capital Economics writes: “the rapid growth in lending over the past couple of years helped to fuel a bubble in the property sector, which has now well and truly burst. Property prices are falling, non-performing loans have risen sharply, credit growth has slumped and GDP growth has weakened dramatically.”

Bad loans are curtailing growth in Vietnam (paywall). And despite the country’s attractiveness as an investment destination for manufacturers who are leaving China , Vietnam could be the next crisis the IMF will have to step in to solve.

Chinese banks look vulnerable. In 2009-10, China’s state owned banks lent a record 17.5 trillion yuan, under government orders to stimulate the economy. Much of this debt was used to funded unsustainable and unnecessary make-work projects. And the banks are now slicing, dicing and hiding the bad loans inside investment products sold to retail investors that look remarkably like Ponzi schemes.

The debt surge has not inflated bubbles in stocks, property or consumer credit. In the UK, Ireland and Latvia consumers became highly indebted, and spending dried up when their homes fell into negative equity and banks cut their credit card limits. China’s state banks have restricted their exuberant lending to state-owned companies and local authorities, and do not even extend credit to SMEs.

Capital Economics points out: “although property prices have been rising quickly in recent years, incomes have been rising faster.” The consultancy also notes that the Shanghai Composite index has under-performed the MSCI Emerging Asia Index since 2008.

But there are other ways Chinese banks could drag the economy down. If liquidity dries up, that may curtail current stimulus projects that are keeping people in jobs. And if Beijing needs to bail out its banks, depositors will probably pay in the form of low savings rates on deposits, which could stifle consumer spending.

Hong Kong has a huge property bubble, but does not face imminent danger.

Hong Kong real estate is over valued, due to low interest rates in the Chinese territory and the US. People are borrowing a lot to buy property. And hot money is flooding in from overseas. But as Jake Van Der Kamp explains in this article for the South China Morning Post, at around 43% of average household income, mortgage payments are not really a problem. He recalls that during “ the pre-1998 property bubble… mortgage payments at one point absorbed more than 100% of household income.”

Around half of Hong Kong’s banks’ total lending is in the form of real estate loans, Capital Economics calculates. But consumers in the Chinese territory, are not over-leveraged. Mortgage borrowers need to pay deposits worth at least 30% of property values. And the mortgage delinquency ratio is just 0.01%.

A property price crash could occur when hot foreign money leaves the Hong Kong housing market. Capital Economics says property prices need to fall 30%. In a crash scenario, the territory’s locals are likely to shoulder falling home values without rushing to sell. Hong Kong has a chronic land shortage, so prices will surely rise again. But a property slump will undoubtedly put the brakes on consumer spending. As Capital Economics writes:

“Private consumption is likely to be hit hard if property prices fall sharply, as consumers would cut back on spending in response to a fall in their wealth. The construction sector is also likely to be badly affected if property prices fall, while there would also be reduced demand for a number of other associated sectors, including estate agents, furniture, and other household goods.”