How Chelsea is “flipping” young soccer players to avoid financial regulations

Chelsea is the bookies’ favorites to win the English Premier League, which begins again next week.

Chelsea is the bookies’ favorites to win the English Premier League, which begins again next week.

The main reason for this is the club’s summer transfer dealings. (They finished third last season.) As is Chelsea’s predilection, they have signed a small number of established players at premium prices: Spanish striker Diego Costa, for £32 million ($53.9 million), playmaker Cesc Fabregas for £27 million ($45.5 million) and Brazilian left-back Felipe Luis for £16 million ($26.9 million).

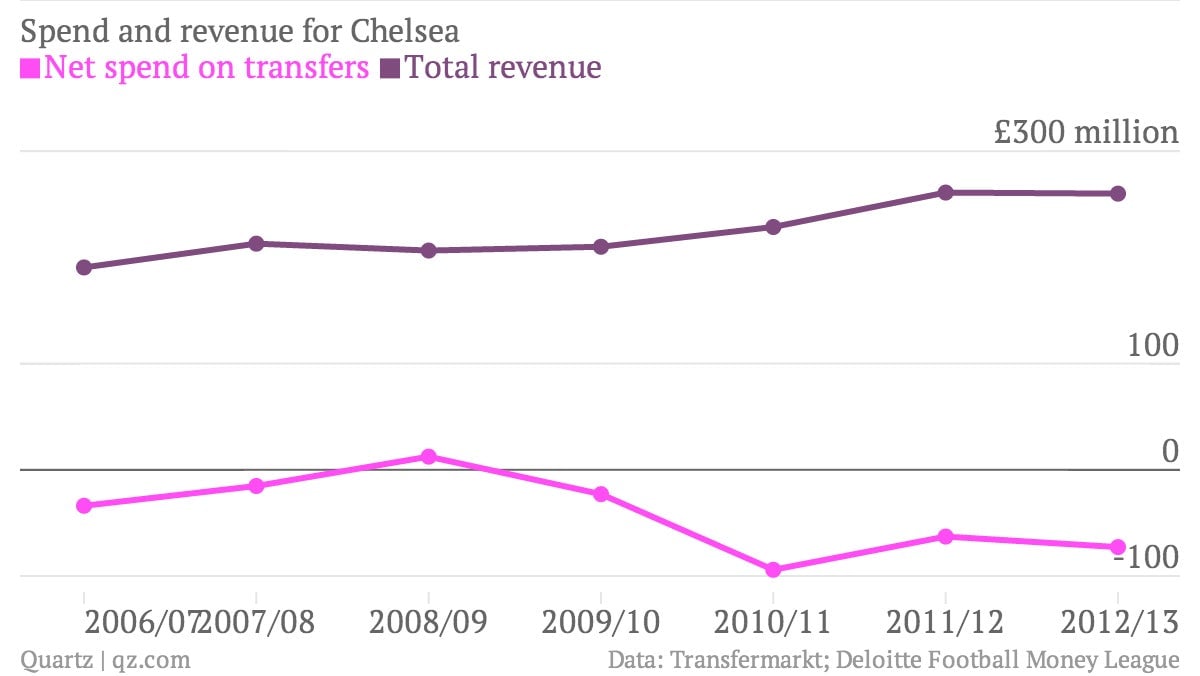

Since the club was bought by a Russian oligarch, Roman Abramovich, a decade ago, it has become a synonym for spending. In the Abramovich era, it bought 26 players for fees of £15 million ($25.2 million) or more in that period. Chelsea is able to afford this because Abramovich underwrites the team’s losses with his personal fortune. The club has made a profit in just one of the past 10 years, and its cumulative losses in that time amount to £650 million ($1 billion). Thanks to Abramovich’s investment, the club has enjoyed the most successful period in its history, winning the Premier League, Champions League, and pile of cups. It is a model that has been aped by clubs across Europe: Manchester City, AS Monaco, Paris Saint-Germain, and Shaktar Donetsk are all bank-rolled by billionaires.

The sport’s governing body in Europe, UEFA, is concerned about the effect that such clubs are having on the competitiveness of European leagues—and the financial respectability of football. In 2009, UEFA introduced financial fair play (FFP) rules which limit the losses that clubs are allowed to make. It gave a compliance period, and for the clubs which failed to comply by the end of last season (2013/2014), stiff punishments were lined up a few weeks ago. This has ramifications for clubs such as Chelsea, whose success on the field is based on an aggressive transfer strategy. But the club’s recent transfer dealings suggest that Abramovich and his advisers are—as one might expect—a step ahead of UEFA.

Take young Belgian forward, Kevin de Bruyne, who had been ear-marked as a future star by a host of clubs when playing for Genk as a teenager. Chelsea bought him for around £7 million ($11.7 million) in 2009. They immediately loaned him out to a German team, Werder Bremen. He impressed in Germany, and the following year Wolfsburg, one of Bremen’s rivals, offered Chelsea £18 million ($30.3 million) for him. Chelsea accepted and he was sold in January 2014, at a profit of more than £10 million ($16.8 million). Chelsea performed the same trick with another Belgian player: Romelu Lukaku. He was bought at age 18 from Anderlecht for £18 million ($30.3 million) and loaned out for a year each to two English clubs. He proved himself an effective player in England and was bought by Everton this summer for £28 million ($47.1 million).

These are two of many examples. According to Transfermarkt, Chelsea had 18 players out on loan for the 2013/14 season. The majority of these are young players with as-yet-unfulfilled talent, whom Chelsea bought cheaply and have loaned to clubs elsewhere in Europe. These clubs are carefully chosen so that they will give the loanees lots of game time, but will not be direct rivals to Chelsea. This means the players get a long period in the shop window. Their sales then provide the profits for Chelsea to reinvest in Costa, Fabregas, and the rest. It is a clever business model.

It is not, however, what UEFA had in mind. The governing body wants the biggest clubs to match their expenditures to their incomes to ensure that their rivals, who cannot afford to be frivolous, are able to compete for players. This idea does not work if Chelsea’s extensive scouting network hoovered up the best talent several years before. There are other concerns too: clubs selling their youngsters to Chelsea are receiving lower transfer fees than if the players had stayed and built their reputations at home. The players themselves must also recognize what signing for Chelsea represents. Now, more often than not, it is to help the club balance its books, not to become a Premier League star.

This is the unintended consequence of the new regulations. By attempting to increase competitiveness, UEFA has helped to create a secondary market in player trading. For Chelsea, the buying, repackaging and selling of young players is becoming a revenue stream—just like broadcasting, tickets and sponsorship. It is now up to UEFA to decide if it wishes to move the goalposts again.