This is either an incredibly good, or bad, sign for the global economy

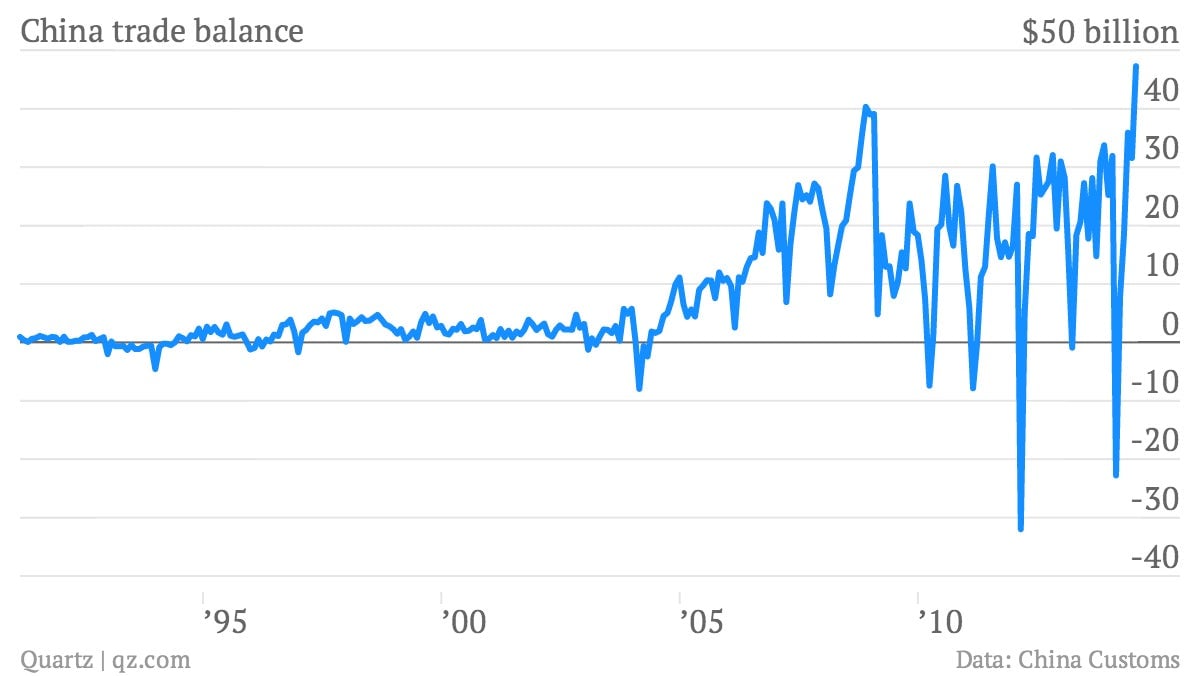

China’s trade surplus surged to a record high $47.3 billion in July, topping the previous peak set in November 2008. On the one hand this is good news; it suggests that the global economic system that has driven growth for the last decade is making a return.

China’s trade surplus surged to a record high $47.3 billion in July, topping the previous peak set in November 2008. On the one hand this is good news; it suggests that the global economic system that has driven growth for the last decade is making a return.

On the other hand, not all of the dynamics that fueled the previous round of growth were good for the world’s economic health.

In the previous decade, the Chinese government leaned heavily on the nation’s export sector for growth—in part by keeping currency undervalued, which makes Chinese products cheaper overseas. The job of the US and Europe largely was to consume. Meanwhile, a whole host of commodity-producing countries—we’re looking at you, Australia—made their living by peddling the raw materials that the Chinese factories needed.

All that was supposed to change in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. China—among other emerging market giants—was supposed to rebalance its economy away from exports toward domestic consumption, as were the commodities countries that supplied China. Meanwhile, developed economies like the US and euro zone were supposed to rely a bit less on consumption for growth. The new wave was supposed to promote a more durable, less crisis-prone world economy.

Everything about today’s trade report suggests that isn’t happening. China is exporting more. Commodities countries are feeding it more. (By volume, iron ore imports, for example, rose 12%.) The consumer economies are consuming more, as the economic recovery gains strength in the US and takes hold in Europe. (China’s trade surplus with the EU and the US widened by 37% and 17% respectively, compared with the prior year.)

In theory, surging exports should mean a rise in China’s currency. But in practice, the yuan is under control of the government, which will keep it low by forcing people to exchange dollars for freshly printed RMB. The government then takes those yuan dollars and lends them, en masse, to the US government. And the wheel keeps on turning.