One of the biggest cracks in the financial system still isn’t fixed

The types of people who go to conferences at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York are talking once again about overhauling the tri-party repo market.

The types of people who go to conferences at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York are talking once again about overhauling the tri-party repo market.

Just about everybody else is completely checked out on the topic, and understandably so. The repo market is tricky. It’s filled with the kind of impenetrable finance-speak that leaves a sticky film on your brain.

There’s a reason for that. The repo—short for repurchase—market was basically invented by lawyers, the certified masters of opaque, brain-sliming language. Anyway, here’s what you need to know.

Repos are loans

Economically speaking, repos are loans. But technically they’re agreements to sell something—usually a bunch of bonds—with the promise of buying it back, within a few days at most, at a higher price. (The price increase is, effectively, the interest payment. The stuff you sell and buy back is, basically, the collateral.)

Repos are a legal invention

Why would you structure a loan like that? Bankruptcy law.

Say you lend money to someone who winds up going bankrupt. Your collateral is supposed to protect you from a loss. But in practice, that collateral is now frozen up in a bankruptcy process, in which you and all the other dimwits who lent money to this deadbeat fight to get something back.

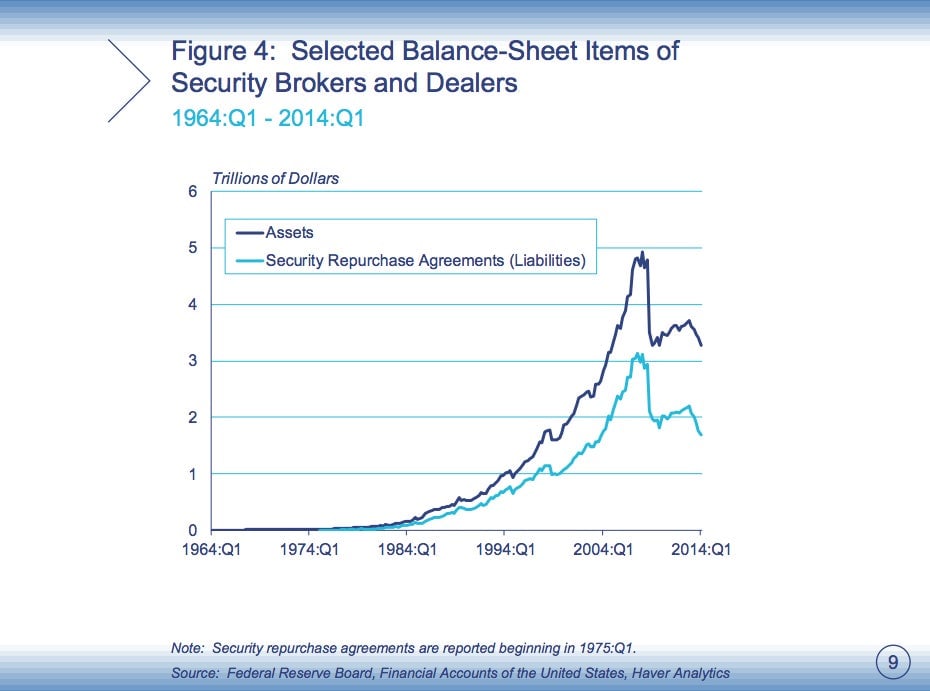

Repos were supposed to solve that problem because, technically speaking, you hadn’t “lent” money, but instead “bought” a bunch of bonds from a “seller.” You were free to sell the stuff—wink, wink—that you “bought”—more winks, elbow nudge—and get your money. The use of repos exploded first in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

The repo market’s exemption from bankruptcy law was—for certain kinds of collateral, like US government bonds—codified in 1984. A 2005 bankruptcy law overhaul expanded the definition of a repo to cover any stock, bond, or other kind of security.

Repos are leverage and, therefore, dangerous

In the financial press, repos usually are described pretty much as they were in the Wall Street Journal today:

The large and opaque market for repurchase agreements helps keep finance and trading moving, allowing hedge funds, investment banks and other financial firms to borrow and lend short-term funds, often overnight.

That’s true. But not particularly helpful. The bottom line is that repos are leverage. They are a way for banks to use borrowed money, instead of their own, to take positions in the market.

When times are good this works pretty well. But in a crisis, things get bad quickly. During the most recent crisis, repo market lenders—mainly cash-rich institutions like money market mutual funds—started watching the market value of their collateral fall, got spooked, and stopped lending so freely.

With less money available to finance the bond purchases, banks had to sell assets. That pushed the prices of collateral down further. More lenders pulled back, more assets had to be sold. That ensuing death spiral played a big part in the near collapse of the US banking system.

Surely, we’ve fixed this problem with the financial system

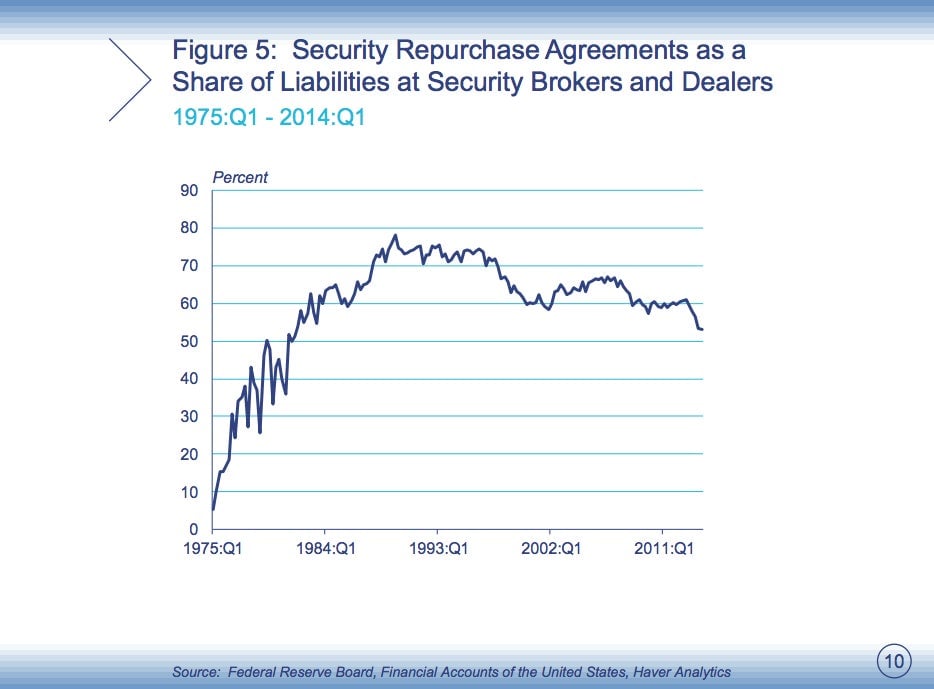

We haven’t. Big banks have cut down on their reliance on repo funding, but not by much. “Their reliance on a wholesale funding model that is subject to runs remains surprisingly unchanged,” Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren said in a speech yesterday.