Three Georgia teens made an app to crowdsource police accountability

The recent deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner at the hands of policemen have spurred calls to curb police violence in America. But a critical element to understanding the problem is missing: data. There’s no comprehensive database of law-enforcement misconduct, and without reliable statistics, it’s more difficult to identify abusive police departments and hold them accountable.

The recent deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner at the hands of policemen have spurred calls to curb police violence in America. But a critical element to understanding the problem is missing: data. There’s no comprehensive database of law-enforcement misconduct, and without reliable statistics, it’s more difficult to identify abusive police departments and hold them accountable.

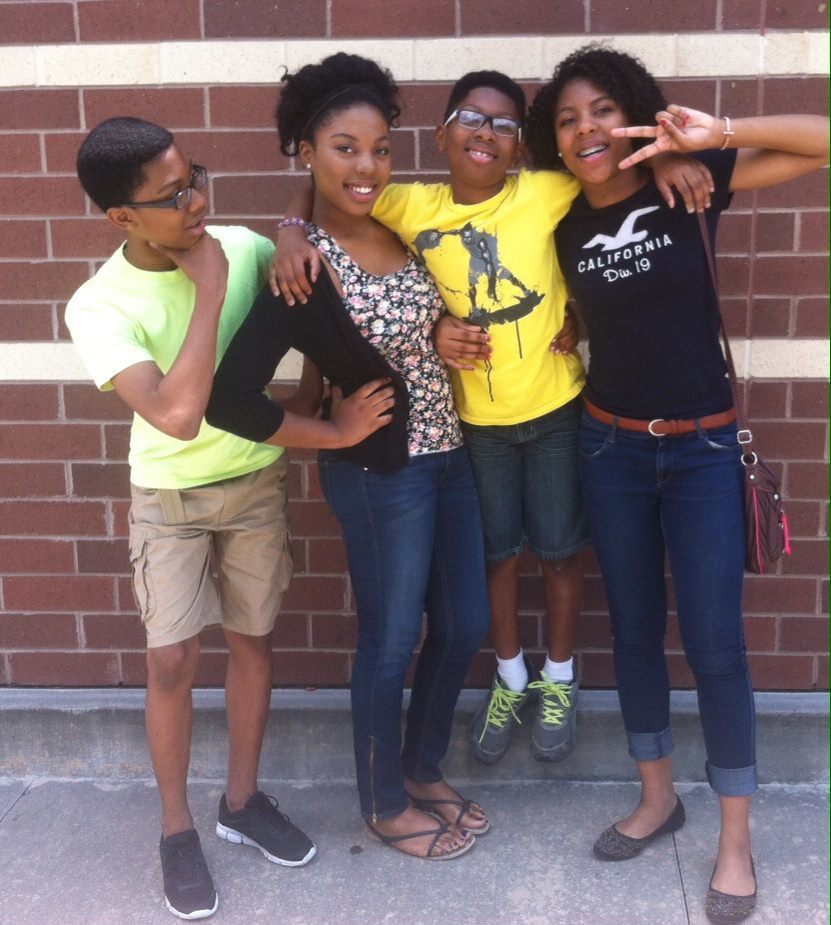

Three teenage siblings from Georgia want to help. Today, they’re releasing Five-O, an app for Android and iPhone that aims to crowdsource a nationwide police-ratings database—a Yelp for police departments, as one of its young developers describes it.

Five-O asks users to log their interactions with the police, including details about the incident (“Was the stop legitimate?” “Were you physically assaulted?”) and a description of the officer (badge number, race, gender). Officers are rated with an A-to-F letter grade. Those grades are converted into an average score and collected (along with other anonymous information from the submissions) in a database that can be searched by location.

“If you’re thinking of moving somewhere and you want to know what’s the rating, how good are the police stations in my area, or how positive are the interactions that take place here, you’ll have a way to go check that out very simply and easily,” Asha Christian, who is 15 and a sophomore in high school, tells Quartz.

Asha and her siblings Ima (16) and Caleb (14) started programming four years ago, using free tools like MIT’s Scratch and App Inventor. Five-O is their first app, but they have two more in production through their company, Pinetart: Coily, to rate and review hair products for black women, and Froshly, to connect incoming college freshman.

Five-O is the latest in a series of high- and low-tech citizen tools created to monitor police. Copwatch started in 1990 in Berkeley, California, to combat harassment of the homeless, and has since gone nationwide. Two years ago, the New York Civil Liberties Union released an app to document stop-and-frisks, joining other apps that surreptitiously record police. And of course plenty of people film their interactions with cops (even when they’re wrongly told they’re not allowed to) and share the results on social networks like Instagram, Vine, and Twitter.

Five-O is a little different. It intends to centralize data from across the US, not only to track abuse but to create incentives for police departments to do better. “We’ll definitely highlight the positives so that they can be an example for any negative interactions taking place,” Ima says. They also plan to add a function for police to respond to complaints.

That pragmatic approach came out of conversations the teens had with their parents about police abuse. “One of the main messages they tried to convey to us was to try to focus on creating solutions when we see a problem,” Ima says. “Talking about an issue is very important because it brings awareness, but ultimately finding solutions is going to have a more positive effect.”