Apple’s sweet spot is the people who buy iPads and laptops together

IPad sales are falling—but the sky is not. We’re merely dealing with a healthy case of expectations adjustment.

IPad sales are falling—but the sky is not. We’re merely dealing with a healthy case of expectations adjustment.

The tablet computer has always felt inevitable. The desire to harness the power of a computer in the comfortable form of a letter-size tablet with a keyboard, or perhaps a stylus for more natural interaction—or why not both?—has been with us for a very long time. Here we see Alan Kay holding a prototype of his 1972 Dynabook (the photo is from 2008):

Kay prophetically called his invention a personal computer for children of all ages.

For more than 40 years, visionaries, entrepreneurs, and captains of industry have whetted our appetite for such tablets. Before it was recast as a PDA, a Personal Digital Assistant, Steve Sakoman’s Newton was a pen-based letter-size tablet. Over time, we saw the GridPad, Jerry Kaplan’s and Robert Carr’s Go, and the related Eo Personal Communicator. And, true to itsEmbrace and Extend strategy, Microsoft rushed a Windows for Pen Computing extension into Windows 3.1.

These pioneering efforts didn’t succeed, but the hope persisted: ‘Someone, someday will get it right’. Indeed, the tablet dream got a big boost from no less than Bill Gates when, during his State of The Industry keynote speech at Comdex 2001 (Fall edition), Microsoft’s CEO declared that tablets were just around the corner [emphasis mine]:

“The Tablet takes cutting-edge PC technology and makes it available wherever you want it, which is why I’m already using a Tablet as my everyday computer. It’s a PC that is virtually without limits—and within five years I predict it will be the most popular form of PC sold in America.“

Unfortunately, the first Tablet PCs, especially those made by Toshiba (I owned two), are competent but unwieldy. All the required ingredients are present, but the sauce refuses to take.

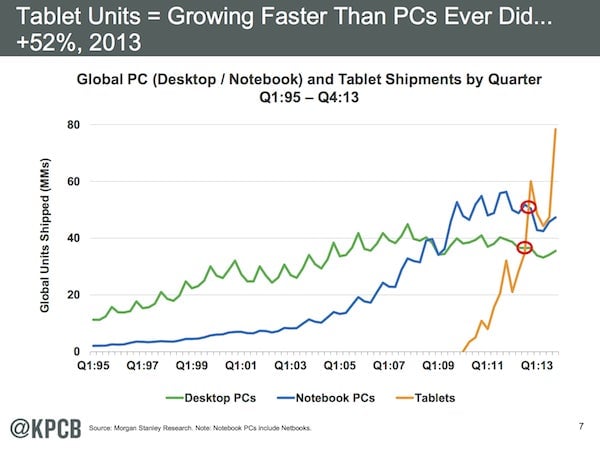

Skip ahead to April 2010. The iPad ships and proves Kay right: The first experience with Apple’s tablet elicits, more often than not, a child-like joy in children of all ages. This time, the tablet mayonnaise took and the “repressed demand” finally found an outlet. As a result, tablets grew even faster than PCs ever did:

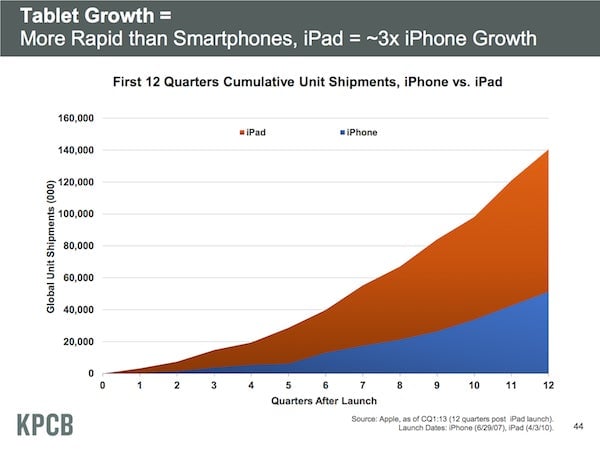

In her 2013 report, Mary Meeker showed iPads topping the iPhone’s phenomenal growth, climbing three times faster than its more pocketable sibling:

There were, however, two unfortunate aspects to this rosy picture.

First, there was the Post-PC noise. The enthusiasm for Android and iOS tablets, combined with the end of the go-go years for PC sales, led many to decree that we had finally entered the “Post-PC” era.

Understandably, the Post-PC tag, with its implication that the PC is no longer necessary or wanted, didn’t please Microsoft. As early as 2011, the company was ready with its own narrative, which was delivered by Frank Shaw, the company’s VP of Corporate Communications: Where the PC is headed: Plus is the New “Post.” In Microsoft’s cosmos, the PC remains at the center of the user’s universe while smartphones and tablets become “companion devices.” Reports of the PC’s death are greatly exaggerated, or, as Shaw puts it, with a smile, “the 30-year-old PC isn’t even middle aged yet, and about to take up snowboarding

(Actually, the current debate is but a new eruption of an old rash. “Post-PC” seems to have been coined by MIT’s David Clark around 1999, causing Gates to pen a May 31st, 1999 Newsweek op-ed titled: Why the PC Will Not Die…)

Both Bill and Frank are right—mostly. Today’s PC, the descendant of the Altair 8800 for which Gates programmed Microsoft’s first Basic interpreter, is alive and, yes, it’s irreplaceable for many important tasks. But classical PCs—desktops and laptops—are no longer at the center of the personal computing world. They’ve been replaced by smaller (and smallest) PCs—in other words, by tablets and smartphones. The PC isn’t dead or passé, but it is shape-shifting.

There was a second adverse consequence of the iPad’s galloping growth: Expectations ran ahead of reality. Oversold or overbought, it doesn’t matter, the iPad (and its competitors) promised more than they could deliver. Our very personal computers—our tablets and smartphones—have assumed many of the roles that previously belonged to the classical PC, but there are some things they simply can’t do.

For example, in an interview with the Wall Street Journal, Tim Cook confides that “he does 80% of the work of running the world’s most valuable company on an iPad.” Which is to say Tim Cook needs a Mac for the remaining 20%…but the WSJ quote doesn’t tell us how important these 20% are.

We now come to the downward trend in iPad’s unit sales: -2.29% for the first quarter of calendar year 2014 (compared to last year). Even more alarming, unit sales are down 9% for the quarter ending in June. Actually, this seems to be an industry-wide problem rather than an Apple-specific trend. In an exclusive Re/code interview, Best Buy CEO Hubert Joly says tablet sales are “crashing,” and sees hope for PCs.

Many explanations have been offered for this phenomenon, the most common of which is that tablets have a longer replacement cycle than smartphones. But according to some skeptics, such as Peter Bright in an Ars Technica op-ed, there’s a much bigger problem [emphasis mine]:

“It turns out that tablets aren’t the new smartphone…[t]hey’re the new PC; if you’ve already got one, there’s not much reason to buy a new one.Their makers are all out of ideas and they can’t make them better. They can only make them cheaper.”

Bright then concludes:

“[T]he smartphone is essential in a way that the tablet isn’t. A large-screen smartphone can do…all the things a tablet can do… Who needs tablets?”

Hmmm…

There is a simpler—and much less portentous—explanation. We’re going through an “expectations adjustment” period in which we’ve come to realize that tablets are not PC replacements. Each personal computer genre carries its own specifics; each instills unique habits of the body, mind, and heart; none of them is simply a “differently sized” version of the other two.

The realization of these different identities manifests itself in Apple’s steadfast refusal to hybridize, to make a “best of both worlds” tablet/laptop product.

Microsoft thinks otherwise and no less steadfastly (and expensively) produces Surface Pro hybrids. I bought the first generation two years ago, skipped the second, and recently bought a Surface Pro 3 (“The tablet that can replace your laptop.”) After using it daily for a month, I can only echo what most reviewers have said, including Joanna Stern in the WSJ:

“On its third attempt, Microsoft has leapt forward in bringing the tablet and laptop together—and bringing the laptop into the future. But the Pro 3 also suffers from the Surface curse: You still make considerable compromises for getting everything in one package.”

Trying to offer the best of tablets and laptops in one product ends up compromising both functions. In my experience, too many legacy Windows applications work poorly with my fingers on the touch screen. And the $129 Type Cover is a so-so keyboard and poor trackpad. Opinions will differ, of course, but I prefer using Windows 8.1 on my Mac. We’ll see how the upcoming Windows 9, code name Threshold, will cure the ills of what Mary Jo Foley, a well-known Microsoft observer, calls Vista 2.0.

If we consider that Mac unit sales grew 18% last quarter (year-to-year), the company’s game becomes clear: The sweet spot on Apple’s racket is the set of customers who, like Cook, use MacBooks and iPads. It’s by no means the broadest segment, just the most profitable one. Naysayers will continue to contend that the prices of competing tablets are preordained to crash and will bring ruin to Apple’s Affordable Luxury product strategy…just as they predicted netbooks would inflict damage on MacBooks.

As for Bright’s contention that tablet makers “are all out of ideas and they can’t make them better,” one can easily see ways in which Google, Lenovo, Microsoft, Apple, and others could make improvements in weight, speed, input methods, system software, and other factors I can’t think of. After we get over the expectations adjustment period, the tablet genre will continue to be innovative, productive, and fun—for children of all ages.

You can read more of Monday Note’s coverage of technology and media here.