Your status updates say more about your personality than you might think

Do our Facebook posts reflect our true personalities? Incrementally, probably not. But in aggregate, the things we say on social media paint a fairly accurate portrait of our inner selves. A team of University of Pennsylvania scientists is using Facebook status updates to find commonalities in the words used by different ages, genders, and even psyches.

Do our Facebook posts reflect our true personalities? Incrementally, probably not. But in aggregate, the things we say on social media paint a fairly accurate portrait of our inner selves. A team of University of Pennsylvania scientists is using Facebook status updates to find commonalities in the words used by different ages, genders, and even psyches.

The so-called “World Well-Being Project” started as an effort to gauge happiness across various states and communities.

“Governments have an increased interest in measuring not just economic outcomes but other aspects of well-being,” said Andrew Schwartz, a UPenn computer scientist who works on the project. “But it’s very difficult to study well-being at a large scale. It costs a lot of money to administer surveys to see how people are doing in certain areas. Social media can help with that.”

For the studies, Schwartz and his co-authors asked people to download a Facebook app called My Personality. The app asks users to take a personality test and indicate their age and gender, and then it tracks their Facebook updates. So far, 75,000 people have participated in the experiment.

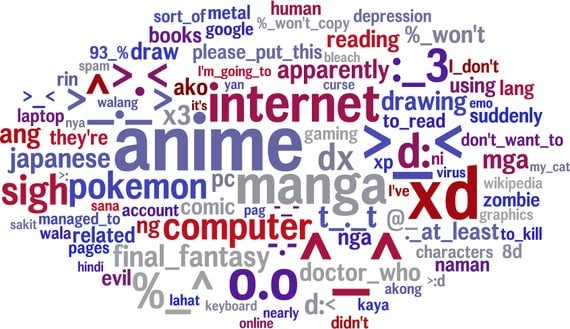

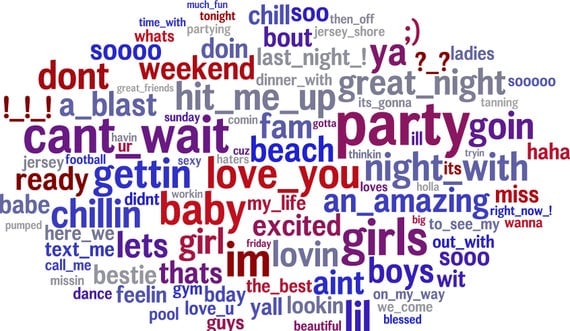

Then, through a process called differential language analysis, they isolate the words that are most strongly correlated with a certain gender, age, trait, or place. The resulting word clouds reveal which words are most distinguishing of, say, a woman. Or a neurotic person.

In the six studies they’ve published so far, they’ve found that, for example, introverts make heavy use of emoticons and words related to anime, but extroverts say “party,” “baby,” and “ya.”

Words used by introverts vs. extroverts

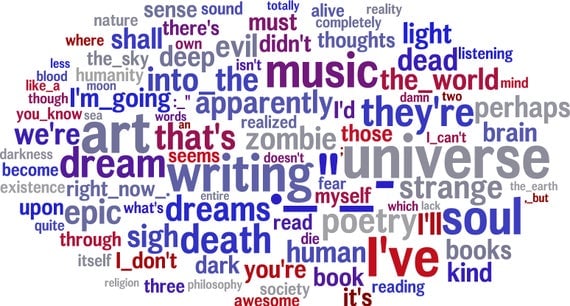

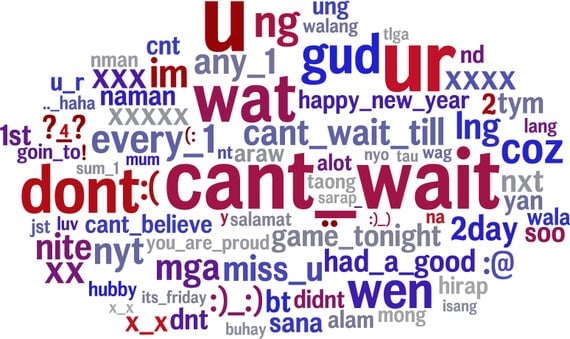

Schwartz and his colleagues have also tracked “openness,” which is “characterized by traits such as being intelligent, analytical, reflective, curious, imaginative, creative, and sophisticated.” Open people talk about “dreams” and the “universe,” apparently, while people with “low openness”—“characterized by traits such as being unintelligent, unanalytical, unreflective, uninquisitive, unimaginative, uncreative, and unsophisticated”—use contractions, misspellings … and misspelled contractions.

Openness and non-openness word correlations

They’ve also analyzed how our use of certain words changes as we age. People are much less likely to be “bored” at 60 than at 13, it turns out, but much more likely to feel proud. Twenty-five year olds tend to mention “drunk,” but 55-year-olds talk about “wine.”

In one of the first studies, the team correlated past Gallup research on life satisfaction with tweets from various counties.

Happy communities, they found, talk about exercise—fitness, Zumba, and the gym—while the sadder ones felt “bored” or “tired.” The more upbeat locales were also more likely to donate money and volunteer, but also to go to meetings. The hidden socio-economic variable is clear: Having money allows you to go rock-climbing, give to charity, and it makes you happier, too.

So far, many of the findings have been rather predictable—which isn’t a bad thing, when it comes to social science.

“Subjects living in high elevations talk about the mountains,” they write. “Neurotic people disproportionately use the phrase ‘sick of’ and the word ‘depressed.’”

But some have shed light on a strange connections between who we are, how we live our lives, and the words we choose to present to the world. For example, “an active life implies emotional stability,” they note. And, “males use the possessive ‘my’ when mentioning their wife or girlfriend more often than females use ‘my’ with ‘husband’ or ‘boyfriend.’”

“It is a very unbiased view of humanity,” Schwartz said of the lab’s work so far. “The data tells the story, and it tells it about people.”