Why Europe is paying Germany to hold its money

Here we are again, through the looking glass.

Here we are again, through the looking glass.

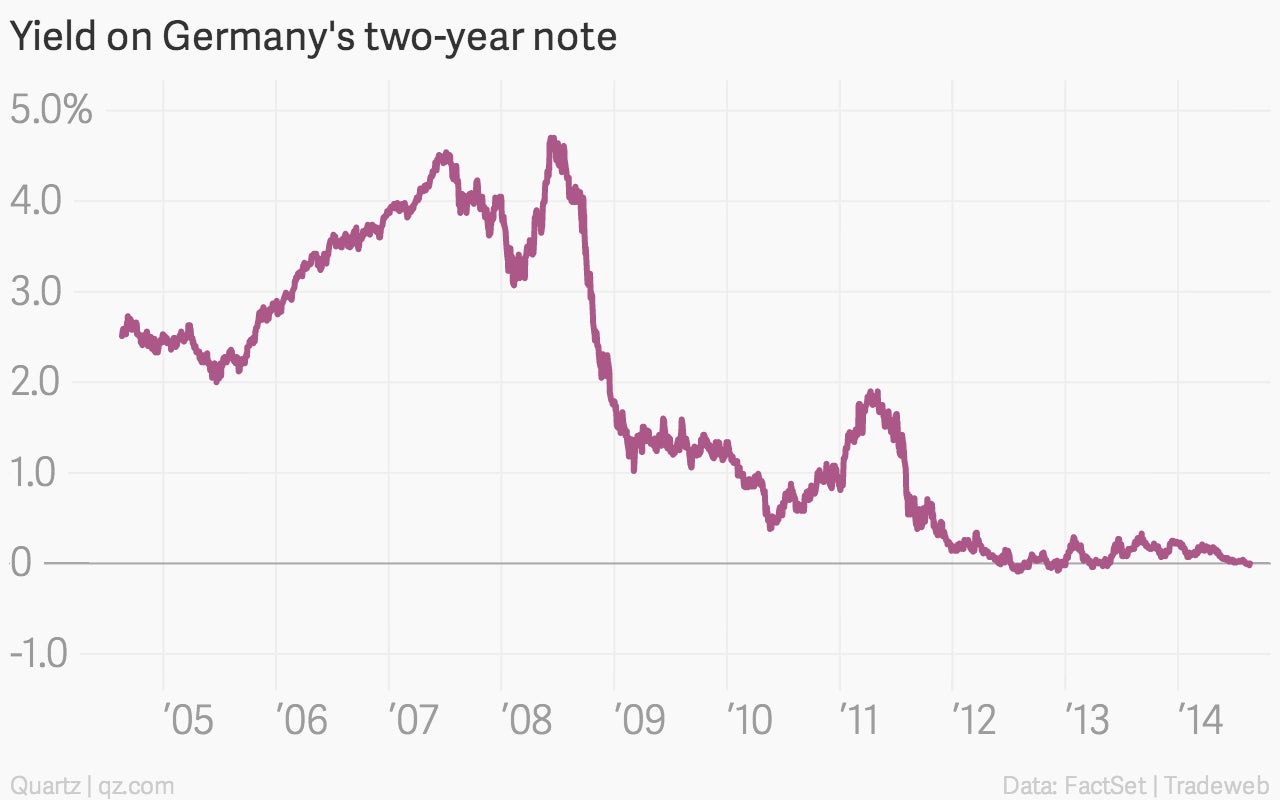

Yields on Germany’s two-year government bond, known to market aficionados as the Schatz (short for the more mellifluous Bundesschatzanweisungen) are hovering around -0.01%. A negative yield means, effectively, investors are willing to pay a slight fee for the privilege of lending their money to the German government.

This isn’t supposed to happen. Usually it’s the borrower that pays to borrow, rather than the lender paying to lend. But negative yields have regularly appeared over the last few years, when low bond yields are pushed even lower during moments of investor jitters.

At first glance, that seems to be the story with the Schatz, as the situation in Ukraine has sparked a dash for safety. But this isn’t the entire story. Across the euro zone, price increases have been very weak, with prices rising just 0.4% in July compared with a year earlier. Many countries already are in deflation—Spain, Greece, Portugal—or tottering on the brink, such as Italy.

More worrisome still is the fact that European bond markets appear to be anticipating continued weakness in prices, even in the strongest of the European economies.

For instance, the so-called five-year breakeven rate for Germany (breakevens are a rough gauge of market inflation expectations) has collapsed over the last few weeks. It now suggests that price increases will average just 0.7% over the next five years.

Falling prices are a real economic risk. They serve as a stiff headwind for economic growth, as falling prices push consumers to hold off on purchases. They also dissuade companies from borrowing more to invest in growth, as it becomes more difficult to pay back debts.

While it is bad for debtors, deflation can be good for lenders, as it makes every repaid euro—or dollar—more powerful than the one that was lent out. And that’s precisely why investors are willing to stow their cash in German bonds and pay a small fee for the service.