François Hollande rearranges the deck chairs on his mutinous ship

Windswept and rain-soaked, François Hollande cut a lonely figure yesterday. Amid a steady drizzle, the French president delivered a speech on an island off the coast of Brittany, the forlorn scene neatly reflected the gloom surrounding his government.

Windswept and rain-soaked, François Hollande cut a lonely figure yesterday. Amid a steady drizzle, the French president delivered a speech on an island off the coast of Brittany, the forlorn scene neatly reflected the gloom surrounding his government.

Before he stepped out into the rain, Hollande had ordered the second cabinet reshuffle so far this year. Stung by an open rebellion against austerity measures, led by Arnaud Montebourg, the outspoken—and now, former—economy minister, Hollande charged prime minister Manuel Valls with forming a new government “coherent with the direction” the president has set for the country (link in French).

The new cabinet, which was just announced, retains key figures like finance minister Michel Sapin and foreign minister Laurent Fabius. The new faces are more in tune with Valls and Hollande’s centrist tendencies, most notably Emmanuel Macron, a 36-year-old former Rothschild banker who will take over Montebourg’s economic brief, and could not be more different from the firebrand left-winger (link in French). A glowing profile in 2012 (French) described him as a “great seducer.”

These days, when the going gets tough, the French blame Germany. Many French politicians associate unpopular austerity policies with Germany’s influence on EU and euro zone rules. For his part, Montebourg talked himself out of his job by railing at the “excessive obsessions of Germany’s conservatives” at a meeting of socialist party members over the weekend. It is up to France to put up a “just and sane resistance” to German-inspired austerity, he said.

Montebourg, who has forcefully intervened in French corporate affairs and called for “deglobalization,” is believed to be courting left-wing voters ahead of a potential presidential run in 2017. On the other side of the socialist-party spectrum is prime minister Valls, whose pro-business leanings stand in increasingly stark contrast to his party colleague Montebourg. Valls may also put his name forward as the socialist party’s presidential candidate when the time comes.

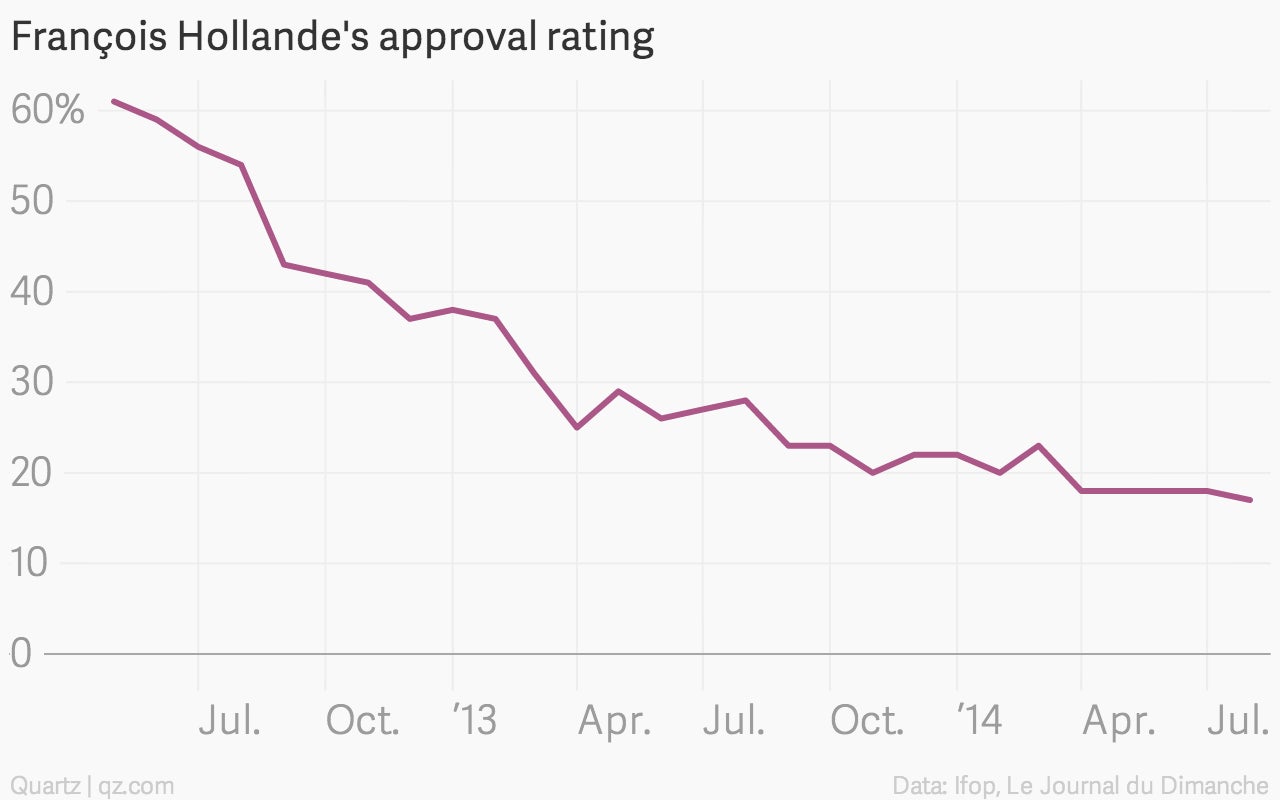

Where does that leave Hollande? The president can in theory run for a second term at the Élysée Palace. But he may not stand a chance. When he took over in May 2012, France’s unemployment rate was 10.3%; today it’s 10.2%. Over the same period, the economy has grown by less than 1%. The president’s approval rating has fallen from 61% in his first month to 17% today—the worst for a president since the founding of the Fifth Republic in 1958. Even in his own party, only 43% approve of his presidency.

The upcoming debate over France’s 2015 budget was already going to be rancorous, as a stagnant economy makes it all but certain that the country will miss its EU-imposed deficit target. The ejection of left-wing rabble-rousers from the cabinet serves to highlight the growing divisions in Hollande’s ruling coalition over austerity, growth, and much else besides.

Given his rock-bottom popularity, Hollande may only be able to keep his party in line by threatening to dissolve parliament and call early elections, in which the Socialist Party would probably lose seats to centrist and far-right rivals. Antonio Barroso of Teneo Intelligence wrote in a client note that even this may not be enough to keep the rebels on side, which will “considerably increase the uncertainty surrounding economic policy.” That means that the clouds over France are unlikely to clear any time soon.