Can Apple get Americans to care about their health?

More than two-thirds of American adults are overweight or obese. Half don’t exercise regularly. Yet Apple, the biggest tech company in the world, thinks it can sell a wearable device that’s supposedly designed—at least, in part—to help people track their health and fitness.

More than two-thirds of American adults are overweight or obese. Half don’t exercise regularly. Yet Apple, the biggest tech company in the world, thinks it can sell a wearable device that’s supposedly designed—at least, in part—to help people track their health and fitness.

Will it take off? And, if it does, could it possibly make a difference? There’s some evidence that it might—that health tracking actually works.

A Pew study from early 2013—after devices like the Nike Fuelband and apps like RunKeeper had launched—found that 69% of Americans tracked “at least one health indicator” for themselves or someone else. These indicators ranged from weight and exercise to blood pressure and sleep patterns. But only 21% of those who kept track said they used technology to do so. (Half said they keep track “in their heads.”) And only 7% used an app or other mobile-powered tool to log their progress.

The good news: Almost two-thirds of those who tracked health data said it had either helped change their approach to maintaining their health, led them to communicate more with doctors, or had affected how they treat an illness or condition.

So perhaps if Apple—through its unique mix of product design, marketing genius, and retail distribution—can get health-tracking hardware and software into more peoples’ lives, and even make it cool, it could actually have some effect on how some Americans approach their health.

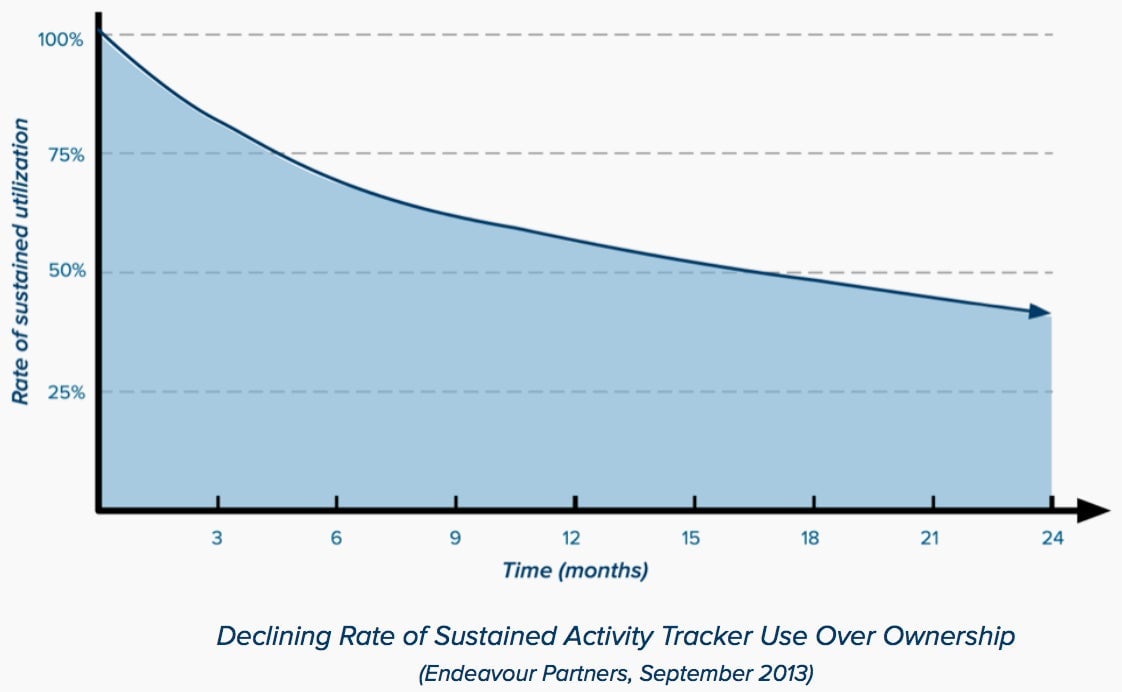

There are two reasons to stay skeptical. First, early activity-tracking gadgets don’t have a promising track record of long-term use. One study (pdf) found that “more than half of US consumers who have owned a modern activity tracker no longer use it.” Of course, it wasn’t until the iPhone that the smartphone market truly took off—perhaps something similar will happen here.

And second, while Apple has been able to attain mass-market status for many of its devices, it still tends to over-index for wealthy Americans. Assuming Apple’s wearable device requires a companion iPhone, it’s more likely to be purchased by richer Americans than poorer. That said, the cost of technology typically shrinks over time, so some company—whether Apple or a rival—eventually could produce more affordable devices. Meanwhile, there are plenty of well-off Americans who need help with health and fitness.

Either way, it’s an interesting question: Can a gadget get America to care about—and improve—its health? We’ll learn more after Sept. 9, when Apple is expected to unveil its wearable.