As Scotland prepares to vote on independence on Sept. 18, the future of its currency has taken center stage.

For the moment, Scotland prints its own notes and uses the British pound, which is controlled by the Bank of England. (Follow?) In the event of independence, Scotland wants to continue to use the pound as part of a negotiated currency union. All three of the UK’s major parties have ruled this out.

Nonetheless, the most likely outcome of a “Yes” vote involves Scotland using the pound anyway. On option: the scenario dubbed “sterlingization,” in which the world’s newest state would have pound notes and coins but no control over its monetary policy. The head of the Bank of England—who, just to make things more confusing, is Canadian—has said that if Scotland were to adopt the British pound on its own, it would need huge reserves of the currency—around 25% of its GDP, or £36 billion—to convince the rest of the world it can credibly act as a lender of last resort in the event of crisis.

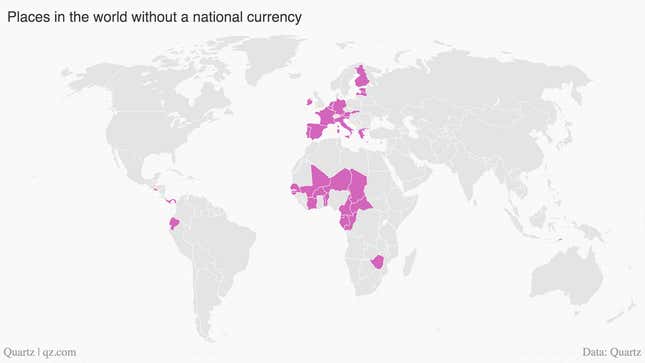

Yet if Scotland were to go it alone, it wouldn’t actually be alone. There are many places that have given up control of their legal tender.

Countries that only use a foreign currency

US dollar: Ecuador, East Timor, El Salvador, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Palau, Turks and Caicos, British Virgin Islands, Zimbabwe.

The US dollar is the most widely used currency in the world, with many countries employing it as an accepted alternative to their own currency. But some have simply adopted the currency as their own, notes and all, in what is known as “dollarization.” They don’t have control over the currency—only the Federal Reserve in Washington sets monetary policy. Both Ecuador and El Salvador adopted the US dollar in 2000, following the creation of free-trade blocs like NAFTA and the EU and the debut of the euro, making even the notion of a “single currency for the hemisphere more plausible and attractive.”

“For Ecuador, adopting the dollar was a way of imposing strict fiscal discipline, in effect by turning monetary policy over to the United States Federal Reserve Board,” the New York Times reported in 2001.

Defenders of dollarization in El Salvador have said it helped to prevent economic crises and attacks from speculators that have befallen countries like Mexico and Argentina—though the cost of converting from the colon to the dollar resulted in prices being round up by fractions of a dollar, creating rising costs for the poorest Salvadorans. And is the Federal Reserve going to think about El Salvador when it slashes interest rates to near zero in the aftermath of an economic crisis and starts printing money? As we saw in 2008 and beyond: Not really, no. Scotland could become the next Norway, small and oil-rich, supporters of independence say. But it could be more like the next El Salvador.

That said, Ecuador chose to issue its own coins—it wanted to avoid the problems of Zimbabwe, which found it too expensive to ship huge quantities of nickels and dimes into circulation but needed much more change, as the cost of most goods had to be expressed in fractions of dollars.

Zimbabwe is a special case. It abandoned its own currency in 2009 and currently has eight official currencies as legal tender: the US dollar, South African rand, Botswana pula, British pound sterling, Australian dollar, Chinese yuan, Indian rupee, and Japanese yen.

Euro: Andorra, Kosovo, Monaco, Montenegro, San Marino, Vatican City.

Following the pattern above, this must be called “euroization.”

Most euro-using countries are neighbors of the European Union, like the principalities of Monaco and Andorra. Montenegro and Kosovo, two of the smallest remnants of what was Yugoslavia, changed currencies twice in less than four years; in 1999, they swapped the Yugoslav dinar for the Deutsche mark, and then each adopted the euro when the notes entered circulation in January 2002.

The turnaround was pretty quick. More than 2.5 billion Deutsche marks were held in Kosovo before 2002, tucked away in mattresses because of a general distrust of banks. These all had to be converted. In the first two weeks of use, for example, Montenegro’s central bank flew in “two planeloads of euro notes and 40 tons of coins.” In Kosovo, 100,000 bank accounts were opened in just the last month prior to the introduction of the euro.

Countries in a currency union

Euro: Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain.

Calls for monetary union in Europe date back to the 1920s, but things got serious when the European Commission (of the European Economic Community, precursor to the European Union) began looking into ways to stabilize fluctuations between the their currencies in the late 1960s. In 1989, the path to monetary union was set out in the Delors report. In 1992, the Maastricht Treaty was signed, which created the EU and set up the path to the launch of the euro in 1999. In 2002, euro notes and coins entered circulation.

There are extensive criteria to join the euro, but nothing in the EU treaties about leaving it—which was unfortunate, as many countries’ finances came under severe strain in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. (None more so than Greece, which at one pointed owed $250,000 for each working adult.) While the euro looked doomed for awhile, the problem was solved using one of the best traditions of capitalism: throwing more debt at the problem. Greece was bailed out—twice—and there was one bailout each for Portugal, Ireland, and Cyprus by the euro zone countries and the IMF. Spain’s banks were bailed out, too, and a 500 billion-euro fund was set up to permanently act as a firewall to prevent this from happening again.

Currently, 18 countries comprising 330 million people use the euro. All the countries have given up monetary authority to the European Central Bank, which sits in Frankfurt.

East Caribbean dollar: Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, St. Kitts and the Nevis, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

The successor to the British West Indies dollar was created in 1976. The East Caribbean dollar is fixed to the US dollar at a rate of 2.7 to 1. The only member of the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States to not take part is the British Virgin Islands—which uses the US dollar, of course.

CFA franc: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Mali, Niger, Senegal, and Togo.

It may surprise you to know that 14 countries in Africa also are dependent on the euro, albeit indirectly.

Strictly speaking, there are two currencies between them: Benin, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal, and Togo use the West African franc. Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon use the Central African franc. Both currencies are at parity and their notes are interchangeable across all 14 countries, but they have different monetary authorities.

The CFA franc was created in 1945 to spare France’s colonies the pain that the post-World War II revaluation in the French franc would do to their much smaller economies. The CFA franc was set at fixed exchange rates against its French counterpart, and is now fixed against the euro.

Alternatively…

Many places both officially and unofficially allow the trade of foreign currencies alongside their own. Residents from Belize to North Korea can spend in US dollars, for example. Panama has had the US dollar as legal tender since 1904, alongside the Panamanian balboa, and was viewed as a special case in Latin America because of the Panama Canal and its huge trade links with the world’s richest country. Others are usually based on relative economic might and regional proximities; Lesotho and Namibia also use South Africa’s rand and small islands like Tuvalu and Nauru use Australian dollars.

Many countries peg their currencies to another nation’s. The Hong Kong dollar, for example, was pegged to the British pound and has been pegged to the US dollar since 1983. It trades within a band of 7.75 to 7.85 HK dollars to the US dollar. How does the Hong Kong Monetary Authority maintain its credibility as the lender of last resort? It has a whopping 120% of Hong Kong’s GDP in foreign-exchange reserves.

The Chinese yuan was pegged to the US dollar until 2005 and has been a managed currency since then—much to the chagrin of the US Congress. The currency is allowed to trade up or down against a basket of currencies up to 1% each day, which was expanded from 0.5% in 2012. Many expect that the band will be widened again and that gains in the yuan will be allowed to accelerate.